Treme, like New Orleans, like America, is stubborn. It does its own thing in its own way. It welcomes outsiders while insisting that they respect whatever passes for tradition, and it resists change until it looks up one day and realizes that change has already come and is calling itself tradition. For all these reasons, David Simon and Eric Overmyer’s HBO series, which airs its finale on December 29, has taken some getting used to. Among its many sweet ironies—one its creators are well aware of and have embedded in this final season’s scripts—is that you don’t appreciate what you had, be it a TV show, a city, or a way of life, until you realize it’s fading away and there’s nothing you can do but say good-bye. The show’s third-to-last episode, “Dippermouth Blues,” which airs tonight, begins, like so many Treme episodes, with a metaphor in monologue. On New Year’s Eve 2008, motormouthed disc jockey, wannabe music star, and sometime politician Davis McAlary (Steve Zahn) expounds on New Orleans’s culture-mixing Creole traditions. “In three weeks, America is about to inaugurate its first Creole president,” he says. “Get used to it.”

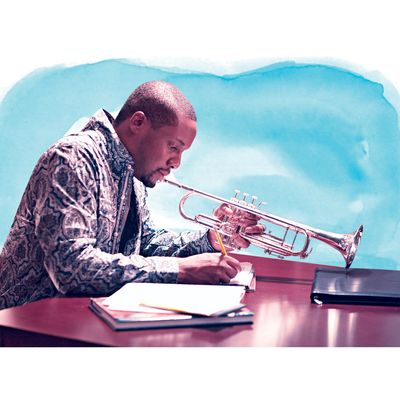

This is a case of do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do, though; every Treme character is coming to terms with immense changes. Some were triggered by the flood of 2005, but none can be solely blamed on it: a wave of gentrification, a crackdown on loud live music that’s tied into a big-money gambit to create a historic jazz district, a resurgence in street violence and police corruption. The individual changes are more mysterious and hard to parse. Davis is grappling with whether to junk his artistic ambitions and become a “respectable” citizen. His girlfriend, Janette Desautel (Kim Dickens), an up-and-coming chef who walked away from a tourist-bait restaurant named in her honor, wonders how far she can get if she can’t use her name on her new place; she also wonders how she ended up with Davis, her on-again, off-again lover, yet again, and whether it means she’s settling. Veteran trombone player and chronic ladies’ man Antoine Batiste (Wendell Pierce) has been fighting to earn a living as a live musician since the show began; now that he’s making decent money as a high-school music teacher (a job he adores) and picking up side bread teaching a handsome white movie star how to play the trombone in a period piece, things should be looking up, but he misses the wild life and is still drawn to it. Antoine’s ex-wife, LaDonna Batiste-Williams (Khandi Alexander), has had the roughest time of any character: She’s survived a rape and a failing marriage (one she probably never should have been in) and has finally settled in with Albert Lambreaux (Clarke Peters, never better), a Mardi Gras Indian chief. But Albert has cancer, so she’s afraid, like Albert’s children, that she won’t enjoy him for long.

Like the best subplots on Simon-produced dramas, Albert’s story gives the others’ plotlines a metaphorical dimension without making a big deal of it. We’re elated by the shots of Albert sewing costumes with his family, railing about his new dietary restrictions, and bobbing to music performed by his jazz-trumpeter son, Delmond (Rob Brown), and we’re devastated when he falls asleep while sewing, or cuts a reverie short, or declines a piece of his daughter’s fried chicken because of the metallic taste in his mouth, but his distress isn’t an isolated sob story. The cancer in Albert’s body is alienating him and making him unrecognizable to others, just as major changes in New Orleans life are prompting other characters to complain that it’s gotten harder to recognize the city they’ve known and loved; yet both processes are presented neutrally here, as destructive evolutions that just happen, and that we may—perhaps should—fight but won’t triumph over. The resigned finality of it should be unbearably sad, yet it comes off as matter-of-fact heroism. We know that this is not the kind of show on which a man being devoured by cancer will suddenly recover; the only question is whether Albert will die between now and the series finale or later, offscreen. Having seen Treme’s final five episodes, I know the answer, but I won’t reveal it here, not just because it’s a spoiler, but because on Treme, as on any Simon show, such matters are beside the point. What happens happens, and you fight the good fight anyway.

Over the years, I’ve gone back and forth over the creative importance of Treme and have questioned certain choices, including the show’s relentless focus on authenticity and “selling out” and its decision to treat every story and every moment as equal, even if it means cutting from something powerful to something mundane and back again—an almost Puritan denial of television’s greatest strength, its ability to expand or contract storytelling emphasis to match an event’s intensity. None of these objections popped up during this final leg, though, because you live in a television series as if it were a place. At a certain point, I decided to accept Treme’s conventions as local customs and traditions, like an outsider who spends a few years in a new land and wakes up one day realizing he thinks of the place as home. This last stretch is a half-season—a grudging parting gift by HBO, which never got big ratings from it—but it doesn’t feel perfunctory or rushed; in fact, it’s the most fully satisfying set of episodes the series has produced. The final montage—scored to “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans?”—is the finest sustained bit of filmmaking in the entire run of the show, affirming the commonality of all of Treme’s New Orleans citizens and that we’re a part of it, and that the bad times and good times, the traditions and changes, were all a part of life.

Treme, HBO, Sundays at 9 p.m.

*This article originally appeared in the December 23, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.