You donÔÇÖt paint; I donÔÇÖt paint. But we both like painting. Could one of us, in our first time ever picking up a brush, re-create by hand, with no oneÔÇÖs assistance, an exact replica of one of the most beautifully complex paintings in art history ÔÇö Johannes VermeerÔÇÖs The Music Lesson? The question is like something out of a Borges short story, imagining the impossible possibility of a one-to-one scale map of the world that covers the world, or the old statistical saw about monkeys and typewriters. The mind-blowing answer given in this documentary foray into the depths of human drive is: Not only can this be done, but we can see it, over the course of 80 quietly intense minutes. Far from deflating our sense of art or giving the lie to past definitions of artistic ability, TimÔÇÖs Vermeer, which opens in New York this weekend, proves that the way to greatness is always in redefining skill and following obsession. (Read my colleague Bilge EbiriÔÇÖs review here.) If this film doesnÔÇÖt leave you saying ÔÇ£Holy shit!ÔÇØ nothing will.

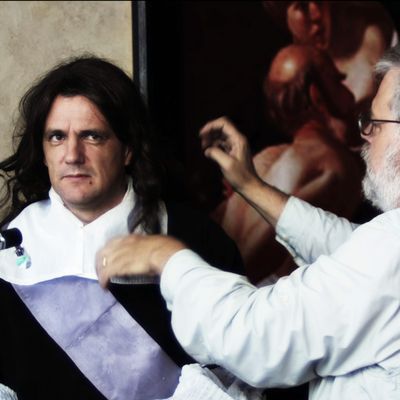

Produced by Penn Jillette and Farley Ziegler and directed by Penns magician partner Teller, the film begins with a fiftysomething hippie type with a bushy white beard saying I have this goal of painting a Vermeer. Before you can say Dont we all? he adds, It will be truly remarkable if I do it  Im not a painter. Ill say. This Obi-Wan guy turns out to be Tim Jenison, a Texas-based inventor of, among other marvelous things, some of the earliest video digitizers. In other words, he knows the difference between the way a camera sees and the way video sees. This turns out to be major. Tims made a lot of money from his inventions, so he also has the time and finances to embark on this tilting-at-windmills task.

We see him go to VermeerÔÇÖs house in Delft and take pictures of the town, and meet with David Hockney in Yorkshire in order to consult about the theory that Vermeer used a camera obscura to paint. Tim goes to Buckingham Palace to see the painting and gets denied, but a half-hour later tries again and is given a private audience with the Vermeer. Next we see him rent a warehouse in San Antonio, cut out concrete walls to make the dimensions right, grind his own lens, mix his own pigments, calculate and design the room where The Music Lesson is set, and build replicas of all the furniture and objects in the room. You want to feel bad about quitting a project because you didnÔÇÖt know how to do something? Watch Tim use a lathe to make furniture and remark, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve never used one of these before.ÔÇØ

Then he sets out to do this thing. The key to TimÔÇÖs discovery is that he comes to realize, with his video-vision, that Vermeer wasnÔÇÖt only using a camera obscura as Hockey and researcher Philip Steadman surmised in their wonderful film and book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering Techniques of the Old Masters. Tim deduces through optics and color studies that Vermeer had to be using something else. He figures out ÔÇö in a way that I still donÔÇÖt entirely understand ÔÇö that a mirror set at a 45-degree angle and the artist bobbing his head up and down, truing the edge of the art with the mirror, is also involved.

Even with this squirrelly discovery, the rest will be familiar to anyone whoÔÇÖs ever set out to make something and then, for whatever inner reasons, must keep making it, no matter what. TimÔÇÖs Vermeer is a real allegory of obsession, possession, commitment, and love. One of my favorite scenes ÔÇö because itÔÇÖs so familiar to me ÔÇö is when we see him on around Day 111 of his Herculean labor, bent over his painting, back frozen, body aching, alone, saying to the camera, ÔÇ£This is making me nauseous.ÔÇØ He presses on, somehow knowing what all artists know in their bones; itÔÇÖs all about the process and what it demands.

Finally, after eight years of research and preparation and 130 days of painting, we see the finished product framed over a bed. It may lack that something extra that Vermeer brings, the touch, blending, facture, and surety. But TimÔÇÖs Vermeer is otherwise perfect. He cries. So did I.