In 1981, pop culture changed forever — only, no one would realize this for a few decades. Thief, Michael Mann’s first theatrical feature, wasn’t a hit upon its release. (He wouldn’t have a real box-office success until 1992’s Last of the Mohicans.) It was only after he became the executive producer and chief stylistic visionary of Miami Vice — contrary to popular belief, he didn’t create the show — a series that wound up defining eighties fashion and aesthetics as much as anything else in movies or TV, that Mann became famous. Thief, which has just come out on Blu-ray and DVD from the Criterion Collection, can be seen as a serious-minded dry run for the flamboyant style of Miami Vice. In fact, it was also a lot more: In its style, themes, and sensibility, Mann’s 1981 crime thriller is the forerunner of dozens of crime thrillers to come. Its painterly visuals, tensely dreamlike mood, and fascination with procedure — these influences have filtered slowly but surely into the culture over the years. You can see it in the grim artfulness of True Detective or the Zen melodrama of Breaking Bad, in the submerged existential torment of Drive or the elaborate psychodrama of Inception.

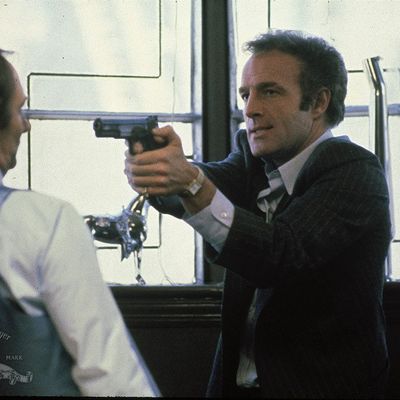

Thief stands between two eras — that of the gritty films of the seventies and the stylish ones of future years. The story of Frank (James Caan), a hard-working, professional Chicago thief (and used car salesman) whose desire to start a family prompts him to take one last, big score for a group of highly corporatized gangsters, Mann’s low-key film focuses as much on its protagonist’s personal life as it does on the job he’s carrying out. That, as well as its unflinching look at the underworld, hearkens back to many of the great American crime films of the previous decade. Indeed, Mann’s interest in making Thief grew partly out of his research while writing an uncredited early draft of the 1978 Dustin Hoffman robbery classic Straight Time.

Frank is no ordinary outlaw. In one of the film’s earliest scenes, he joins a fisherman by the water one morning. Together, they look out at the calm, seemingly endless expanse of Lake Michigan at dawn. (“That’s magic. That’s the Sky Chief, man.”) This is of course a classic Michael Mann moment — tough men looking meditatively at the sky, at the sea, or at both — and it’s the first such moment of its kind in his filmography. (It pops up again in the opening shot of Manhunter, and repeatedly in both the TV and film versions of Miami Vice.) For all his tough talk, Frank yearns for an inexpressible peace. And his longing finds its aesthetic expression throughout Thief in the way Mann merges precise, highly composed shots with the synthesized, New Age sounds of Tangerine Dream’s otherworldly score. You can see some of that here in this Criterion video:

Traditional dramatic structure wouldn’t quite know what to make of this. Thief isn’t so much about a quest for things as it is about a state of being — an attitude. That attitude — that obsession with pose, image, and sound — is part of what would come to be called “the MTV style.” But Mann’s film premiered a few months before MTV launched, and while music videos had already increased in visibility by 1981, his work was key in fusing music video imagery with narrative cinema.

To be fair, many of these elements weren’t particularly new. Anybody who’s seen Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai and La Cercle Rouge (or Walter Hill’s The Driver, for that matter) knows that Mann didn’t invent the poetic existentialism of his outlaw characters. As for his precise, color-coded visuals, at the same time Mann was making Thief, Jean-Jacques Beineix was in France filming the highly influential Diva, which would eventually be pegged as the first film in France’s rather ludicrously named (and short-lived) cinema du look movement, which foregrounded imagery over substance. Mann wasn’t even the first American director to hire Tangerine Dream to compose a soundtrack; William Friedkin had used them for his 1978 thriller Sorcerer. In Thief, their score has surprising range: Industrial, almost musique concrete–like passages seem to dissolve into lush, synthesized melodies. The music doesn’t just help to illustrate or emphasize the actions occurring onscreen. Rather, at times it takes center stage and draws attention to itself, creating new psychological layers and meaning. There aren’t any actual pop songs in Thief, but the music of Miami Vice — whether it’s Jan Hammer’s famous electronic score or the vast array of eighties hits featured on the show — doesn’t feel far away.

Yet Mann brought all of these elements together and combined them with an absorbing, exhaustive attention to detail that was rare in this type of genre film. Many of the roles in Thief are played by actual criminals, people among whom Mann had done research and whom he’d brought on as technical advisors. The elaborate safe-cracking and break-in tools being used in the film are real ones. With Thief, Mann cracked the code on fusing a music-video-style look with a ground-level authenticity, backing the dreamlike imagery and music with a sense of the real. (In this sense, his spiritual cousin isn’t another narrative filmmaker, but rather Errol Morris, who would bring this type of aestheticism into the documentary form in films like The Thin Blue Line.)

This is a stylistic gambit that Mann would perfect in later films like Manhunter and Heat. (Consider the fact that the latter, while inspiring many other films with its cool visuals and eclectic score, was methodical and dense enough that it also influenced a surprising number of armored car and bank robberies, with criminals looking on the film as a kind of how-to guide.) In turn, this is also the approach that runs through so many crime films today. Tony Scott mixed Mann’s ethereal machismo with an adrenaline-junkie style all his own. David Fincher crosses it with a kind of dark, horror-movie quality. Perhaps Mann’s most diligent pupil is Christopher Nolan, who merges Mann’s Zen sensibility with intricate, blockbuster-friendly narratives. Back in the day, John Woo ran with it in films like Hard-Boiled and The Killer, which at times feel like hybrids of Mann, Melville, King Hu, and Sam Peckinpah.

Today, we take this approach — cool imagery, brooding characters, heavy-duty attention to detail — for granted. In 1981, however, it was distracting to many. Artists who put New Age scores and pop hits and poster-worthy visuals in their films were not the kinds of artists who also did rigorous research into their subjects. Critics were understandably mixed. Roger Ebert praised Thief for its ability “to convince us that it knows its subject, knows about the methods and criminal personalities of its characters … It’s a thriller with plausible people in it. How rare.” Vincent Canby at the New York Times was distracted by the style: “This neonlit, nighttime Chicago is pretty enough to be framed and hung on a wall, where, of course, good movies don’t belong … The music by Tangerine Dream sounds as if it wanted to have a life of its own, as if it were meant to be an album instead of a soundtrack score.”

Many others echoed Canby’s criticisms. But today, his words sound like those of someone faced not with a movie, but with an entire generational attitude that is now ubiquitous. Because Thief’s landscape is now the landscape that the modern crime narrative inhabits — a world of procedure mixed with cool, where characters who were once relegated to desperation and madness are now allowed to be contemplative. It’s a world where cops and robbers gain mythic proportions not just for their deeds but for their dreams — where crooks are allowed to have souls, and where those souls can be expressed as much by a carefully struck pose or a precisely cued burst of music as by a line of dialogue.