Written by Peter Ackerman and directed by John Dahl (Rounders, The Last Seduction), the eighth episode of The Americans’ second season is another classic, suffused with feelings of guilt and culpability, and eager to confront head-on the implications of its characters’ actions. The final scene is one of the most wrenching I’ve seen in a TV drama: Henry, son of the show’s married secret spies, has been caught breaking into a neighbor’s house to play their coveted Intellivision video game system, and tearfully confesses and asks forgiveness.

“I know the difference between right and wrong,” he tells Philip and Elizabeth, after the neighbor family catches him snoozing on their couch, video-game console in hand. “I do. It just seemed like no one would even know! And they weren’t there, you guys weren’t here. Once I did it, it just seemed so easy to keep doing it. I know it was wrong, but I’m not gonna do it again. I feel horrible. But they think I’m some kind of criminal, but I’m not … I’m not! I’m a good person, I swear! You know that! You know that! I’m good, I am! I’m a good person, I swear I’m good! I’m a good person, I swear I’m good! I’m not gonna do it again, I swear. I’m good.”

That scene is a knife in the heart, and it offers the best possible refutation to viewers who think the show is full of coldblooded sociopaths. Elizabeth and Philip — and for that matter, Stan and Nina and Oleg and every other major character — know full well that they’re making compromises and taking shortcuts, and sometimes liberties, as they do their job, and that it costs them something: a bit of their humanity, maybe a lot. But they compartmentalize it. As soldiers do.

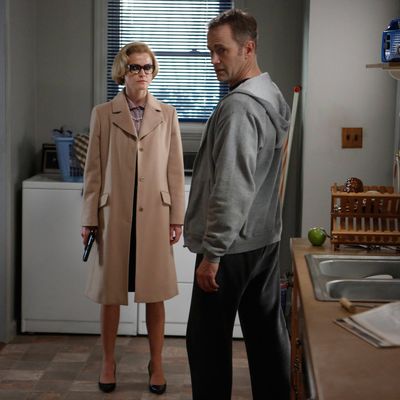

Still it gnaws at them. Elizabeth insists over and over that when it comes to the spy game, a Utilitarian philosophy makes sense, even if it means writing off assassinations, torture, sexual manipulation, theft and all manner of other crimes under the rubric of “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.” But such statements ring hollow when she stands by and watches the betraying Navy SEAL Andrew Larrick strangle the Sandinista Lucia, in the kitchen where she’d come to kill him in retaliation for a past terrorist action that killed her newspaper editor dad. Earlier, Elizabeth had admonished Lucia that even though what happened to her father was horrible, she had to put her rage aside for the greater good of Communism. But you can see in Elizabeth’s voice as she breaks down, and see in her tears, that she doesn’t entirely believe that. “It was for her goddamn country,” she gasps, clinging to her husband.

Phillip is way ahead of her. Some of the tensest scenes in this episode are about the conflict between Elizabeth’s tactical coldness and her husband’s increasingly nagging conscience. He killed an innocent busboy in the season opener, and things have only gotten worse from there. This week comes the revelation that the submarine propeller technology they stole (with approval from Arkady and the Rezidentura gang) was planted, and that a Soviet sub sank because they took the bait, killing 160 sailors. Arkady’s cousin wasn’t on the sub, but he’s in the Soviet navy, so it is not unthinkable that their activities could have killed him. Showrunners Joel Fields and Joe Weisberg said early on that this season’s focus would be family, but “collateral damage” seems to have already eclipsed it, with “effect on family” as fallout from said damage. The spies and their daughter murdered (by Larrick, if indeed we believe he’s the killer) tied these notions together. No wonder the entire season has been colored by dread of something horrendous happening to characters we’ve grown to care about, if not exactly love.

It’s fascinating how The Americans has evolved the tension between Elizabeth and Philip about their relative American-ness and how it affects their identity as Soviets. She’s clearly got a more-Russian-than-thou attitude, and it makes Philip insecure. But even if the show’s treatment of this tension was simplistic in the first season (and I don’t think it was) it has become undeniably more complex in season two. It’s more about Philip worrying that he’s made peace with himself as a killer and all-around rotten person in exchange for American freedoms, be they the ability to bust out in country-western dance at a department story or to impulse buy a new Chevy Camaro with his son and then rock out to “Rock This Town” in the driveway afterward.

The episode makes this equation (America in exchange for your soul) achingly clear in a shot that ends the scene in which Philip’s new handler breaks down while telling him about the 160 dead sailors. He pauses next to the new Camaro and regards it warily, as if he expects it to turn on him. (I love that he didn’t kick the car in anger.) Philip commits great crimes but also what you might call misdemeanors. The most recent of involves tactically editing a tape to make it sound as though Stan and agent Gadd are talking trash about Martha’s looks — a tactic meant to make Martha reconsider her wish to leave the department where “Clark” convinced her to spy. Not for nothing does Philip seem to spend more time looking at himself in mirrors and not liking the face he sees there.

Philip tries to get Elizabeth to admit that she can’t completely shut out the pleasures of capitalist life even as she plots to destroy them. “Don’t you enjoy any of this sometimes?” he asks her. She just keeps evading and evading and evading him. He repeats “Do you like it” three times but never gets an answer. But he knows the answer, and so do we. It’s the same answer he’d give: yes. That’s why he doesn’t want to kill the truck driver out in the woods. And it’s probably why she agrees not to.

Moral compromise is also at the heart of the Stan-Nina-Oleg story line. Every one of them has conflated personal need and pleasure with state business. They’ve all diminished themselves as a result. Stan is now a traitor to his country, having stolen Oleg’s file and given it to him. It was bad enough that he killed an innocent coworker of Nina’s as revenge for Philip killing his partner last season. He just keeps compounding his own sins. So does Nina. So does Oleg, who has used his position to, essentially, secure himself a mistress (he and Nina seem to genuinely like each other, but a relationship founded on treachery will always be tainted). “We’re destroying ourselves, and it gets worse and worse whatever we do,” Stan says, in a rare moment of eloquent self-knowledge. It’s all downhill from here, I’m afraid. The closer we get to the end of the season, the tighter the knots in my stomach.