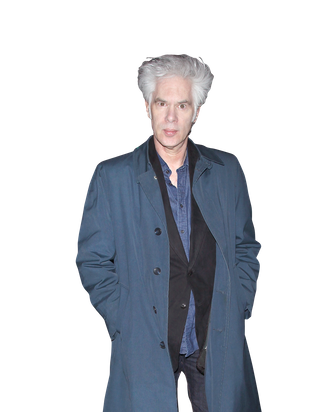

Jesus Christ, Jim Jarmusch is 61 years old. The man who helped define the independent downtown New York film scene in the 1980s through the films Stranger Than Paradise, Down by Law, and Mystery Train can now get senior citizen discounts at Ben & Jerry’s. Maybe it’s telling that his latest, Only Lovers Left Alive, is about vampires. Not unlike his undead characters Adam (Tom Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda Swinton), the strangely ageless Jarmusch (he still has that happy shock of white hair) has seen fads and movements pass by over the years. All along, though, he’s been whittling away at his own very idiosyncratic films, with their characteristic blend of melancholy and deadpan wit. Only Lovers Left Alive may be a vampire movie, but it’s more a love story than horror flick, more a meditation on poetry, music, and worldly experience than a story about fangs and blood. The director sat down with Vulture recently to discuss the personal nature of the new film, his evolving approach to directing, and his certainty that William Shakespeare didn’t write any of Shakespeare’s plays.

Do you feel a particular kinship to the characters in Only Lovers Left Alive?

Yes, I do. I feel very close to a lot of their concerns, though they’re not me. And they’re quite different from each other. I see Adam as a little bit more fragile. He needs to see some of himself reflected back on him, whereas Eve has no need whatsoever with that. She’s open to all the experiences of having a consciousness, [which] to her are enough. I understand, too, when Eva, the sister, refers to them as snobs. They are snobs. That’s part of their character viewed from the outside. I love to read negative reviews; I don’t really read the positives. And someone said, “Yeah, but they’re just snobbish characters.” Well, if you and I were alive for 500, 1,000, 2,000 years, we would certainly appear as snobs to everyone else, because our knowledge and experience would be so much more vast, you know?

Do you ever identify with their snobbishness?

Sometimes, yeah. I hear myself sounding snobbish sometimes when I criticize the way other people do things. It’s not a great quality. I try to check myself because I try to be … what I don’t believe in is telling anyone else what they should do or think. If I had any religious beliefs, that would be the biggest sin. I don’t want to tell anyone else what they should think, feel, or believe. I want to respect whatever they’ve arrived at with their consciousness, and I would like them to respect mine. However, expectations will kill you. I’ve learned that.

All your movies are very personal, but this one seems particularly so. One of your main characters is an artist, and while poetry has been a recurring metaphor in your work, this time an actual poet, Christopher Marlowe, turns up.

Yeah, I hadn’t even thought of those things. Those are both big departures for me. And this might be my first film about artists. Maybe that’s why I have trouble talking about it. I don’t want to demystify the film and I don’t want to explain it. And also this film is very laden with references. Not that I don’t put references to things in all my films — just hoping that maybe if one kid in Kansas gets turned onto William Blake or something then I did my job. But I feel like I put a lot in there this time for people to absorb. Maybe I overdid it. It’s hard to know. I’m too close to the film.

In the film, Marlowe, played by John Hurt, is the author of Shakespeare’s plays, a belief some people share. Do you believe in the so-called Stratfordian Conspiracy?

Yeah, I’m a definite total anti-Stratfordian completely. And yet, in the end, it doesn’t really matter at all who wrote it. But I do think it’s one of the biggest conspiracies, at least literary, perpetrated. And one of the greatest conspiracies ever perpetrated on humans. I think it’s ridiculous. I’m not alone. I’m with Mark Twain and Henry and William James and Sigmund Freud and Orson Welles, Emerson — a lot of people don’t buy the Shakespeare thing. I just put Marlowe in there because another great conspiracy for me is Marlowe’s death. I don’t buy his death. It seems completely absurd also. Whether Marlowe wrote the stuff or somehow was in Italy or whether it’s a combination of Marlowe and others — especially William de Vere, which the film and book Anonymous delved into, and which is probably more likely. But the man William Shakespeare, I believe, was illiterate and couldn’t even write his own name from what we can see. There’s not a single manuscript in his hand that has anything to do with literature. Come on — how could that possibly be true? We have manuscripts in the hand of Marlowe and Thomas Kydd, and his contemporaries who didn’t write as much. Where did it all go? They needed some kind of front man. He got rich; we’re not quite sure why. He probably got paid off.

Anyway, I think it’s fascinating and fun and interesting. But in the end, like I said, it doesn’t matter. Whoever wrote those sonnets and those tragedies, specifically — wow, I don’t care who it was. I’ve had Stratfordians get so upset I thought they were gonna burst into tears. I understand, because they’ve invested their whole being into the mythology of this man. But the truth is that everything we know about the man William Shakespeare fits on four pages of text — that’s it. Anyone who writes anything longer, they’re making shit up. That’s just the way it is, no matter what they say. I’m not buying it. I never will. I don’t know if it’ll ever come to light or be proven. They did a pretty damn good job of covering it up.

Has your directorial approach changed over the years? With Stranger Than Paradise, I remember you once saying something like 70 percent of what you shot made it into the film. But recently I saw a documentary about you on the set of Limits of Control in which you talked about how shooting for you is a process of gathering images without knowing how or if they’ll make it into the film. That seems like a big change. Is it just the fact that you have bigger budgets now?

There’s certainly an element of, if I were very restricted like Stranger Than Paradise and had a very limited amount of film stock to shoot, that would affect my procedure. So that’s part of it. But I’ve also learned that the editing room is where the film tells you what it wants to be. So, editing is where I really build the film. And I don’t just shoot the script, I shoot a lot of things and I’m not sure which scenes will end up in the film necessarily. But the thing is, the beauty of cinema is to walk into a room and be taken somewhere where you don’t know you’re being taken. And if you wrote it and shot it, that quality is removed for you, so I personally have trouble always being analytical or seeing my films.

I recently had a nice chance to interview Alexander Payne onstage for the Directors’ Guild for Nebraska. Payne is fantastic, and a real cinephile. I love talking to him. But he’s the opposite. He only shoots the scene in the script and he only shoots the dialogue in the script. And me, I swear I have 30 minutes of outtake scenes from this film that I love. I love the scenes. It’s not like, “Oh, that didn’t work.” It’s that the film didn’t want them all. While shooting, I’m not sure which one the film’s gonna want and which one it’ll reject. But I had to cut like 30 minutes of very lovely scenes, and there’s nothing wrong with them. There’s just too many of them.

Do you improvise a lot?

We try to. I encourage improvisation. I do have a script. I like to shoot dialogue that’s sort of in the script, at least as a basis, and then often when I get a take that I’m happy with, I’ll say, “Now try something else, man. Make up something or try the same scene with no dialogue but try to say the same thing.” So yes, I like improvisation and I feel very collaborative with actors always. And all actors are different. Some of them are comfortable improvising and some of them aren’t. That’s an interesting thing to find as you’re collaborating.

It’s funny to hear you say that. Over the years, if there was anything one characterized as Jarmuschian — and I apologize for using that word —

[Laughs.] It’s okay!

… you’d think: control. You’d think: deadpan. And the idea that you’re the kind of director who actually likes to improvise is interesting to hear. What’s that thing Bertolucci always quotes Jean Renoir saying? “Always leave a door open on set.”

Nicholas Ray said it, too. “If you’re just gonna shoot the script, why bother?” But then there are more formulaic approaches where that’s a strength. Alexander Payne is an example. A more rigorous example would be, with a different kind of film, Hitchcock. Alexander’s films, there’s more poetry in a certain element of the writing, so I just really believe as many filmmakers as there are, there are that many ways to make the film. I still believe that.

I know you’re not one to watch your films again when they’re done.

No.

So I have no idea if you’ll have a response to this. But while I was watching Only Lovers Left Alive, I couldn’t help but think back to Dead Man. It felt almost like a companion piece/response to that other film in some weird way. Quite aside from the contrast in the titles, one seems to be very much about the cycles of life, and about this character, who, while passive, takes the whole world in. In Only Lovers, you’ve got two characters that are completely removed from the cycles of life because of who they are.

They are the two films of mine that do have kind of larger themes about the circularity of the life cycle and time passing and a historical overview on things. Whereas all my other films are just right there in the present, so they’re not about an overview or a larger philosophical thing really. And certainly there are philosophical elements to Ghost Dog and stuff, but these two are really more, they step back a little further in their view of things.

Does genre help you when you’re trying to tell a more metaphorical story? It seems like in recent years, you’ve started reinventing certain genres: The hitman movie, the vampire movie.

Well, using the word “metaphor” is the key, because when you accept a genre as a frame, you’re immediately inviting the metaphorical, or you are opening the door and beckoning it right in. That’s kind of fun and freeing. But definitely as soon as it’s a genre, there’s some kind of metaphorical level implied. That’s what I like about it. In this case, their vampiric state is a metaphor for the fragility of humans. And the Western is a frame, too, and within that frame, you can paint all over the place, you could go crazy, because you have the frame to contain you somehow. So you could be more wild within it than you could if you didn’t have it. I don’t know what that means, but …

You once said that all your films start off serious and as you work on them they become funnier and funnier. Is that still the case?

Yeah, completely. I thought this one was very dark and mysterious and brooding. But it gets funnier as we go along. I can’t help that. When funny things happen, I capture them. It’s like second nature somehow. So I have to try hard to be serious, even to make it not totally comical and ridiculous.

You’ve maintained your independence for pretty much your whole career. But what’s the closest “they” ever got to you? Have you ever had to take some notes from an executive, even if you just laughed them off?

I made two films with Focus Features, and they were perceived as a kind of mini-studio. And I did take notes from them, but they were very open, and they said, “Feel free to discard anything.” But that was not in any way problematic. If anything, I was interested in their notes. And the second time, they had almost no notes. That was really the closest I’ve come. I take notes from investors, anyway, if they want to give me notes, when I show them a rough cut. I’m happy to hear back what they say. But contractually, in all those cases, I have final cut. So I don’t have to do anything.

Can you name one incisive note you received?

Yes. Jeremy Thomas [the producer of Only Lovers Left Alive] gave me notes several times, both on the script and during the shooting, that I had too many references. And I knew that I did, and knew that I was going to remove them. So I removed some from the script, some while we shot, and more in the editing room. And I was already aware of this, but I was happy when he would remind me, you know? Because it needed a balance there, and I had way too many. It was bordering on being pretentious or forcing things on the audience, which isn’t the point. And the best thing he said to me was, ‘Whenever there’s information in the film that makes you think, ‘Why is he telling her this? Wouldn’t she already know?’ then you’re telling the audience.” So that was very helpful. So whenever there were places where, wait a minute, why are they telling each other this? Take that out of there. So that was very helpful.

You obviously were part of New York art and music scene for a long time in the 1970s and ’80s, but what was your first memory of New York?

Of ever in New York? Oh, man, I came here with my parents in the mid-1960s from Akron, Ohio. I remember that. I remember the Woolworth store on 34th Street. I remember my sister collecting Beatles cards. I remember a subsequent trip. I remember being in Chinatown, and on St. Marks Place with my father, with a lot of what he called “beatniks” hanging around, right by Gem Spa where they sold egg creams, which I had no idea what they were. And my father saying to me, after some sort of bearded, beatnik types were cruising around, he said, “Take a good look at these people, Jim. They’re all hopped up on dope!” And he used that term — “hopped up on dope” — which just sounds like from, ’50s movies. I remember that very distinctly.