SundayÔÇÖs unsettling hologram performance at the Billboard Awards showed, once and for all, that the thriving Michael Jackson industry doesnÔÇÖt need Michael Jackson to survive. Jackson is a global corporation, a portfolio of investments ÔÇö a lucrative moneymaking machine that hums along, with or without a human at the controls.

Xscape ÔÇö┬áa potpourri of exhumed Jackson demos and discarded tracks, organized by L.A. Reid and fleshed out by top producers including Timbaland and Rihanna hitmakers Stargate ÔÇö is currently the No. 2 album in the country. While itÔÇÖs a bit odd to see the King of Pop lagging behind the Black Keys, the current No. 1 act, being second best isnÔÇÖt too shabby when youÔÇÖve been dead for five years. All in all,┬áXscape ÔÇö┬áeight ÔÇ£newÔÇØ songs in total, which go back as far as 1983 ÔÇö is an admirable effort to make a full meal out of reheated leftovers.

This week┬áBillboard reported that Jackson is now the first artist in history to score a top 10 Hot 100 hit in five consecutive decades, thanks to XscapeÔÇÖs first hit single, ÔÇ£Love Never Felt So Good.ÔÇØ With the success of the album, itÔÇÖs likely that Jackson will shoot to the top of another list this year ÔÇö the annual Forbes list of top-earning dead celebrities. Last year Jackson was No. 1 on that list, earning an estimated $160 million. JacksonÔÇÖs financial situation isnÔÇÖt the only thing to have gotten a boost since his death; his legacy has been revitalized, too. Hits in recent years by Justin Timberlake, Pharrell, and Daft Punk all owe a distinct debt to the King of Pop; the long shadow that Jackson cast over pop music has only gotten longer since his passing.

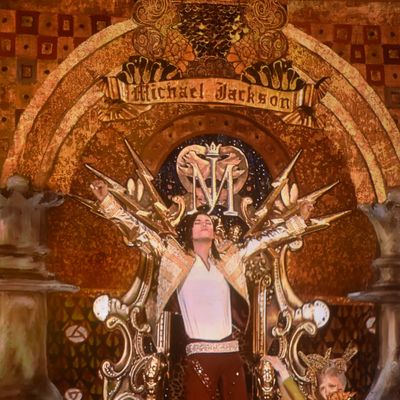

Dead celebs who do well in the afterlife are nothing new, of course; artists ranging from Elvis Presley to Bob Marley still earn tens of millions a year. But there was something particularly grotesque about the holographic Jackson spectacle last Sunday. There were the highly publicized lawsuits that raged between warring hologram companies mere days before the Billboard Awards, putting the agonies of capitalism on full display. There was the sinking feeling among viewers of being duped by elaborate smoke-and-mirrors marketing ÔÇö we soon learned that ÔÇ£JacksonÔÇØ was a floating digital face grafted onto an impersonatorÔÇÖs body, not a full hologram. The performance itself was wooden, not at all up to JacksonÔÇÖs exacting standards. The impersonator danced robotically, flanked by a phalanx of dancers, against a glistening over-the-top backdrop that looked like something out of a Fellini movie.

Being only a hologram from the neck up was particularly strange in JacksonÔÇÖs case, because JacksonÔÇÖs ever-morphing, surgically altered face was such a focal point during his life. JacksonÔÇÖs digitized visage on Sunday was an effulgent depiction of Jackson in the early ÔÇÿ90s ÔÇö a white face with red lips and a smoothed-over nose, framed by black, wavy hair and assertive eyebrows. The Tupac hologram of a few years ago, in contrast, felt like a blas├® video game. The Michael Jackson apparition played out like brutal and terrifying science fiction ÔÇö a J.G. Ballard novel come to life.

Part of what made JacksonÔÇÖs holographic performance so bizarre was the song itself: ÔÇ£Slave to the Rhythm,ÔÇØ a song on Xscape that was originally recorded in 1991 during the Dangerous sessions. The song is not half bad, though itÔÇÖs easy to see why it was kept on the cutting-room floor until 2014. ÔÇ£SheÔÇÖs a slave to the rhythm,ÔÇØ Jackson sings, ostensibly about a woman. ÔÇ£She danced through the night/In fear of her life/She danced to a beat of her own,ÔÇØ Jackson continues urgently, filling in gaps with his requisite ÔÇ£hee-heesÔÇØ and perfectly placed hiccups. But the song sounds autobiographical ÔÇö you could think of it as JacksonÔÇÖs ghost, talking about his own tortured afterlife. Jackson, five years after his death, is a slave to the rhythm ÔÇö shackled by the corporate interests that refuse to let him rest in peace. HeÔÇÖs the phantom in Brian De PalmaÔÇÖs creepy 1974 classic Phantom of the Paradise ÔÇö┬áthe sad, undead guy in the skintight black leather outfit who forgot that he signed a recording contract in his own blood, whoÔÇÖs now trapped in a recording studio and forced to craft megahits for eternity.

Jackson is an unending source of income, spinning out in all directions until the end of time. Like the Star Wars franchise, there will be sequels ÔÇö and when the sequels are done, there will be prequels. Hundreds of unused songs ÔÇö demos, outtakes, and other bits and pieces ÔÇö are said to be in JacksonÔÇÖs vaults. As holographic technology inevitably improves, the possibilities for live performances in the future will be endless. But perhaps we should leave Jackson be instead of trying to digitally reanimate him for eternity. In the words of Obi-Wan Kenobi in Revenge of the Sith, after witnessing a Darth Vader hologram slay a Jedi, ÔÇ£I canÔÇÖt watch any more.ÔÇØ