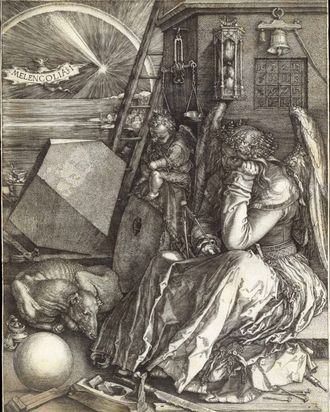

Albrecht D├╝rerÔÇÖs┬áMelencolia I┬áis considered one of the biggest downers in all of art history. It has been ever since D├╝rer made it in Nuremberg in 1514. D├╝rer is the Leonardo da Vinci of the Northern Renaissance, a giant who merges mathematics, theology, psychology, and allegory with a visual force that resonates and shakes still.┬áMelencolia I┬áis the NorthÔÇÖs equivalent of LeonardoÔÇÖs┬áVitruvian Man, that touchstone of the Italian Renaissance depicting a male figure with doubly outstretched arms, which signals a new combination of thought, science, art, and observation. Right now the Met is observing the 500th birthday of D├╝rerÔÇÖs peerless foray into pathos, creativity, and self by hanging one print of the engraving made when the copper plate was fresh, and another better one made after the plate darkened a bit. (The later one lets you see more.) There are also a handful of supporting images, including a great copy made by Jan Wiery in 1602. The D├╝rers murmur and stir. This is an ineffably implacable image of a mind ÔÇö possibly a creative one, perhaps D├╝rerÔÇÖs, certainly aspects of ours, when weÔÇÖre caught up in racing thoughts or daydreaming or stuck on an idea or spinning in circles.┬á

A word of advice before viewing this singular image: DonÔÇÖt try to figure it out as if it were a puzzle. The picture encompasses more than you can wrap your mind around. The endless interpretations and countless cults devoted to divining D├╝rerÔÇÖs real meaning will only limit what your own eyes and gut can tell you.

Melencolia I is small, only nine by eight inches, yet itÔÇÖs packed to distraction: ItÔÇÖs compositionally claustrophobic. Your eyes dart every which way; thereÔÇÖs no visual center. The space in the picture lurches and spirals. The image presents as frontal and very shallow. Then it starts crisscrossing in different directions. A part of the background recedes into deep space. The right side is dominated by a winged female figure with her chin and cheek rested fixedly on her hand, as if sheÔÇÖs pausing to think or reflect. SheÔÇÖs been said to be horrified, terrified, in agony. These reads strike me as overstated, histrionic, although they do get at the multidirectional vectors here. Something subtler rustles.

The upper-left-hand part of the picture has something like a spatial wormhole. Way back, we spy the sea and a distant horizon, a tiny town, and a bizarre bat displaying the printÔÇÖs title under a rainbow. Under this corkscrewing hole in the picture is a solid carved geometric polyhedron. Some see a face in this rock. Opposite this is a so-called magic square, a grid of16 numbers. Each row and column totals 34. Some say that this sum signifies ChristÔÇÖs age at the time of his death; others that the 15 and the 14 in the center bottom row are the date and the year of his motherÔÇÖs death, in 1514. The great thing about this square, however, is that to occupy yourself with it lets you experience the mental or psychic equivalent of resting your chin in your hands, being lost a little, or midstream. (It gets to D├╝rerÔÇÖs genius when you realize that viewing the picture as a riddle actually duplicates one of the states of torpor the image may depict.) Although all the numbers in the square add up, they donÔÇÖt reveal anything. ItÔÇÖs like looking at a tree in late autumn: You see its structure, but you still donÔÇÖt know it. Over and over, D├╝rer produces a strange sensation of in-betweenness, unknowability, being caught up in the workings of your own mind. ┬á

IÔÇÖve wandered a little into in the symbolic weeds, so IÔÇÖll back off and leave you to look. Scan and notice the empty scale in perfect balance, an hourglass with equal amounts of sand above and below, unused tools strewn about, a bell with clapper hanging straight down silently, a sphere standing still. When I look at this image I feel my mental rhythms meander, running away from me, or circling, unspooling, showing me parts of myself that fleet past my consciousness without being grasped. I feel stalled, but in a place that makes me strangely sad while still being gladly aware of things. I want to say itÔÇÖs the strange bliss of elsewhere.┬á

D├╝rerÔÇÖs Melencolia I is on view in the Metropolitan Museum of ArtÔÇÖs Gallery 690 through July 14.