In the mid-1980s, writer/artist Frank Miller crafted two of the most influential Batman stories ever told: The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One. It’s not hard to see why they’ve had such a potent legacy. Even today, three decades after they were published, they remain thrilling and insightful. But I swear to God, if one more filmmaker uses them as a source text for a Batman movie, I’m going to smash my face into a concrete wall.

Today is a great day to reassess Miller’s twin graphic novels’ influence on the multibillion-dollar Batman movie industry, because today is Batman Day. Batman Day is, of course, an entirely made-up holiday that DC Entertainment declared to celebrate its ever-lucrative Caped Crusader’s 75 years of publication history (as well as move product and build buzz in advance of this weekend’s San Diego Comic-Con).

Take a look at the initial announcement of Batman Day and you’ll see how much DC relies on Miller: It mentions only one comic published between 1939 and 2014, and that comic is The Dark Knight Returns. Frank Miller’s Batman is still the primary ambassador between DC and the world at large. And, most important, every single Batman movie director has paid fealty to Miller’s ‘80s tales. His grim and gritty take on ol’ Batsy has crowded out all other cinematic approaches to the character.

What was once an innovation is now a cliché. It’s been nearly 30 years, Hollywood. If you want to stay relevant, you have to update your inspirations.

******

Before we go any further, here’s a quick rundown of these two unendingly influential story arcs. The Dark Knight Returns, published in four installments in 1986, is an extremely grim vision of a near-future Batman in a crime-ridden Gotham (reminiscent of Death Wish–era New York) that went to seed after Bats hung up the cape and cowl years prior. When Bruce Wayne finally reenters the fray, he beats the shit out of young punks, spits out one-liners through gritted teeth, drives a military-grade Batmobile, and even takes on Superman in a climactic tussle.

Batman: Year One, published in four parts the very next year, jumps back in time to reimagine Bruce’s very first adventure as Batman. His target is not superpowered villainy, but rather the very human evil of organized crime. He makes rookie mistakes and manufactures a costume. He forms a friendship with a good-hearted cop named Jim Gordon. By the end, Batman is ready to be the hero we all know and love.

DC had been struggling to push Batman in a darker direction for about a decade. As of 1986, the infamously campy 1960s Batman TV show still had its claws dug into the American popular consciousness, and the comics publisher’s attempts to distance itself from that silliness had failed to make a splash.

They turned to Miller, already famed for his moody revamping of Marvel Comics’ Daredevil series, and found that he was on the same page as them. “I felt that superhero comics had really been held back by a misperception that they were just for kids,” he later said. “The comic book world had become so utterly pleasant and safe that the idea of somebody dressing up in tights and fighting crime just seemed beside the point.” When he took his revisionist urges to the printed page, Miller struck the right chords while offering new readers an easy on-ramp, as his tales didn’t rely on the minutiae of past Bat-continuity. The Dark Knight Returns and Year One were smash hits. Miller had successfully rebranded Batman as a brooding, introverted street-fighter with a near-sociopathic commitment to eradicating crime by any (non-lethal) means necessary.

Hollywood immediately took notice. When Tim Burton took the helm of a long-delayed effort to bring Batman to the big screen for the first time since the ‘60s, he desperately wanted his hero to build on Miller’s ideas. “When the graphic novels first started coming out back in the ‘80s,” Burton would later recall, “you saw that there was potential to look at these things from different perspectives.” Sure enough, his 1989 megasmash Batman was steeped in Miller’s dark vigilante justice and pithy action-hero zingers. And thus began a nauseatingly common refrain from creators and fans, one that has become almost a sacred article of faith: The closer an onscreen Batman is to Frank Miller’s Batman, the better.

Burton’s 1992 sequel Batman Returns remained steeped in bleak urban violence (and perhaps copped its title from The Dark Knight Returns). Joel Schumacher strayed into neon glitter and nipple-showcasing chestplates for Batman Forever and Batman & Robin. But even Schumacher worshipped at the Miller altar: In 1998, he told Entertainment Weekly that his ideal Batman movie would be an adaptation of Batman: Year One.

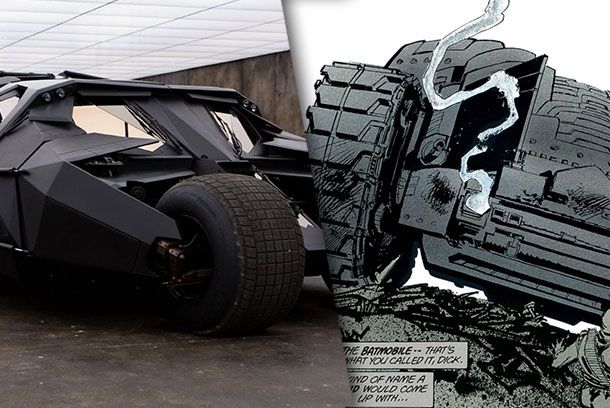

Miller’s grip on the screen has become a stranglehold in the past decade. Christopher Nolan’s 2005 Batman reboot Batman Begins was blatantly based on Miller’s ideas: the early-career tribulations of Wayne and Gordon — as well as a number of specific plot devices and characters — were lifted directly from Year One, and Batman’s vehicle of choice was directly based on The Dark Knight Returns’ tanklike Batmobile. That latter comic’s setup — a retired, past-his-prime Batman hits the streets after a long absence — became the setup for 2012’s The Dark Knight Rises.

There’s no end in sight. The upcoming re-reboot of Batman, in Zack Snyder’s Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, will be hugely influenced by The Dark Knight Returns. The first photos of Ben Affleck show a costume that’s a near-direct copy of the one seen in that story. So does the Batmobile. Hell, when DC announced the movie a year ago, it did so by having an actor read a monologue from The Dark Knight Returns onstage at the San Diego Comic-Con. It’s ridiculous and embarrassing for DC to act like this kind of inspiration breaks new ground.

Experimentation is what has kept superhero comics alive from Batman’s first appearance until this year’s Batman Day. Indeed, The Dark Knight Returns and Year One were huge risks when they hit the stands. But on the big screen, DC is beating Frank Miller’s ideas into the ground.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with Miller’s twin Batman epics. But there is something creatively bankrupt about studios focusing on them so monomaniacally. As Miller himself once said, “There are 50 different ways to do Batman and they all work.” Our fate is sealed for Batman v. Superman, but we have to imagine a better future. If an ambitious filmmaker wants to make a truly innovative Batman movie, he or she needs to put Frank’s hard-boiled sagas back on the shelf. Luckily, there are more than enough other Bat-tales to devour.

Here are some inspirations any screenwriter or director can find at a local comics purveyor:

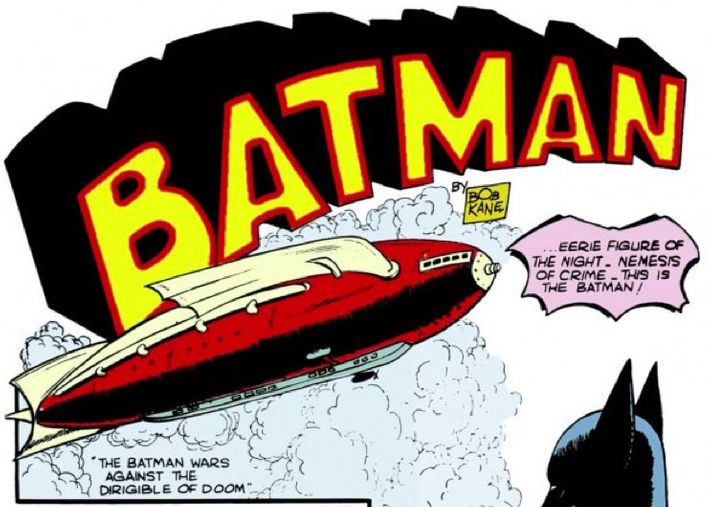

The first Batman stories. It’s genuinely surprising how rarely anyone, let alone a big-budget director, has drawn on the early Batman tales of the late 1930s and early 1940s. In those heady days, co-creators Bob Kane and Bill Finger put out stories that read like silent-movie fever dreams. Devilish monks. Eerie zeppelins. Bruce Wayne in a white lab coat doing chemistry with beakers and decanters. Wouldn’t it be fascinating if someone took these stories and made a period-piece Bat-flick? One set in the waning years of the Great Depression, with a hopeless populace learning to accept what Finger termed “this weird figure of the dark, this avenger of evil, the Batman”?

Grant Morrison’s myth-heavy Batman mega-arc. In 2006, DC made a brilliant decision and put one of the comics world’s greatest geniuses at the helm of Batman: Scotsman Grant Morrison. Over the following seven years, in stories that crossed the globe and traveled through time, he radically reimagined the Batman mythos. In his stories, you can find a wealth of concepts that a skilled director could harness. What if Batman is a symbol that’s much bigger Bruce Wayne: a symbol he could pass down to a successor as well as franchise out to culturally specialized sub-Batmen in cities around the world? What if Batman became a father? What if Batman were driven insane and had to rely on protocols he’d set up for himself in the event that he lost his mind? Any one of these conceits — along with the many others Morrison crafted — could make for a gripping and new tonal approach on the big screen.

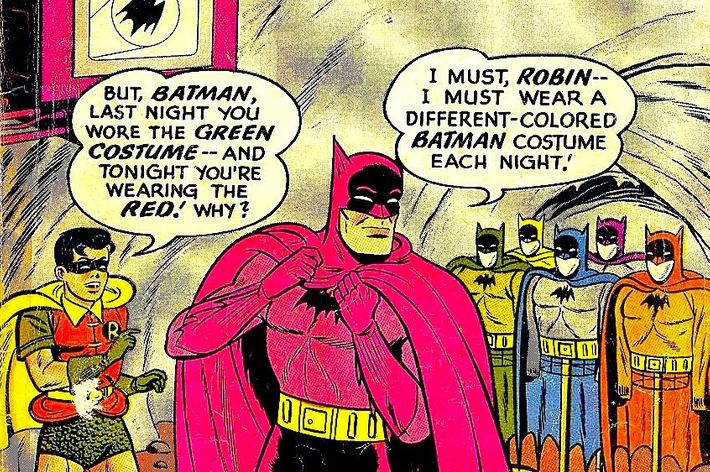

The insane Batman yarns of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Well before Adam West began his televised Technicolor adventures on ABC, the writers and artists on Batman titles were cooking up truly bonkers scenarios for the Caped Crusader and the Boy Wonder. Batman turns into a giant fish! A visit from the dimension-hopping Bat-Mite! The Dynamic Duo fight robots on distant planets! Before you say this stuff wouldn’t work in a modern-day adaptation, check out the incredible animated series Batman: The Brave and the Bold, which aired from 2008 to 2011 on Cartoon Network. (It’s all streaming on Netflix.) It specifically aimed to draw from these strange tales, and although the results were probably too goofy for a multimillion-dollar film, they proved there’s narrative gold in them thar hills. Filmmakers should at least take a look and expand their minds.

The work of Paul Dini. Dini is unique among the creators on this list in that he made his bones doing Batman cartoons before he started writing Batman comics. He was one of the chief minds behind the immaculate Batman: The Animated Series, where he invented fan-favorite Joker sidekick Harley Quinn and completely reimagined Mister Freeze, among other achievements. In the ‘00s, he penned delightful stories in Batman comics, ones that successfully melded suspense and humor — something the Bat movies rarely do. Take, for example, the time a kidnapped Robin caught the Joker off-guard by trolling him hard on some Marx Brothers trivia. Dini proved you can make a Batman story funny without making it campy. If only movie studios could figure out how to do that, too.

Greg Rucka and Ed Brubaker’s Gotham Central. This crime saga was a 40-issue police procedural that ran from 2003 to 2006 and captured the hearts of fans and critics. It followed the exploits of everyday cops working in Gotham, struggling to follow the rules in a city whose protector plays by his own. The Caped Crusader was rarely seen in the series, but it drove home the idea that Batman is not just a person: He’s a force that changes the world around him. Obviously, a Batman movie needs to have more Batman in it than Gotham Central had, so a direct adaptation probably wouldn’t work. But why not draw on the ideas, characters, and tone Rucka and Brubaker set forth? (The upcoming Fox series Gotham, which follows Gordon as a cop in the years before the advent of Batman, will likely pick some of this up, but it’s definitely more inspired by fantastical supervillainy and Miller’s Year One.)

Scott Snyder’s current-day run on Batman. Comics continuity is a complicated business, so I’m going to oversimplify what happened in the past few years of DC history: In 2011, DC rebooted its entire lineup of comics, meaning creators had wiggle room to rethink every character’s origin story. Along those lines, writer Scott Snyder has reinvented Batman’s early days in a way that respectfully — but totally — jettisons Batman: Year One. Pick up his incredible (and still ongoing) Zero Year story line to find a high-concept, goose-bump-inducing tale of a young Dark Knight thrust into a guerilla war after Gotham is nearly obliterated. Frank Miller’s graffiti-laden Gotham of 1986 was interesting, but its race has been run; Snyder’s bombed-out, weed-ridden, eerily quiet Gotham of 2014 is thrillingly new. And hey, it features a resource-deprived Batman riding a rusting motorcycle while wrapped in a tattered costume and carrying a crossbow, so what more could you ask for?

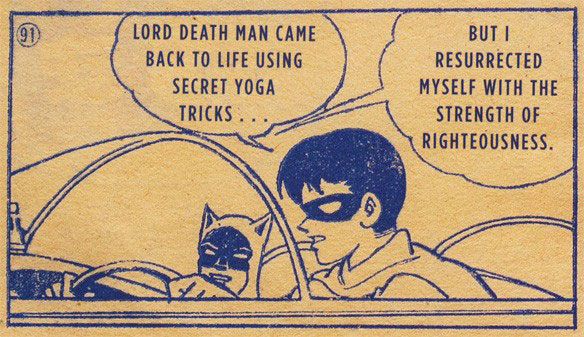

The surreal Japanese Batman manga of Jiro Kuwata. This one is certainly too weird for DC to allow a direct adaptation — but holy smokes, if you’re a filmmaker and you want something to inspire you to push the envelope, you have to dig into Jiro Kuwata. In 1966 and ‘67, Kuwata cranked out stories of Batman and Robin for a Japanese manga publisher, and they’re really something to behold. There are supernatural yoga villains, live burials, telepathic giants — not to mention beautiful manga-penciling techniques. In a perfect world, we’d get a Japanese-language Batman movie directed by Takashi Miike, but one can only ask for so much.

Of course the list of non-Miller perspectives goes on and on. There are as many Batman interpretations as there are stars in the sky above Gotham City. Now that superhero movies are ubiquitous and everyone knows the fundamental tenets of the Batman character, we deserve a Batman movie that takes innovative risks. The Dark Knight Returns and Year One have served their purpose. Let’s hang their jerseys in the rafters and get cracking on something truly new for the big screen.