The most touching thing in Guardians of the Galaxy is its very first opening scene, set in 1988. A young boy, inseparable from his Walkman, watches his mother die of cancer and then runs, in tears, out onto a field, where he’s promptly abducted by a spaceship. The scene positions this entire sci-fi spectacle as a wish-fulfillment fantasy, anchoring its derring-do and frivolity in grief. We read and watch stuff like this to get away, it tells us. So come away with us. Of course, this is just another variation on the old Spielbergian motif of the broken child saved by wonder, but it still works. It’s also an artful dodge, because while this very enjoyable film does return briefly to this scene later on, it mostly avoids anything approaching this level of poignancy for the rest of its running time.

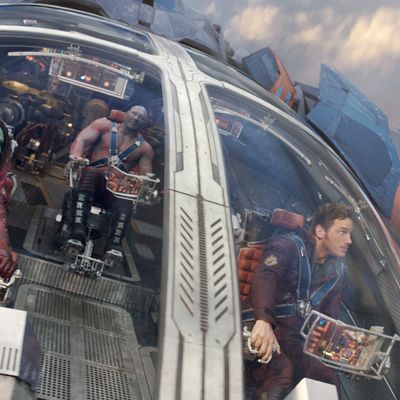

That young boy, 26 years later, has grown up to become Peter Quill (Chris Pratt), who wanders space and calls himself Star-Lord, a “Ravager” whose chief aim appears to be to find, steal, or smuggle cool stuff to sell. After he gets his hands on a mysterious and highly coveted object known as “The Orb,” he’s thrust together with a group of intergalactic misfits: A sociopathic, genetically modified talking raccoon named Rocket, voiced by Bradley Cooper; a giant tree-creature named Groot (who can say only “I am Groot,” but can still somehow get the raccoon to understand him, à la Chewbacca and Han Solo), voiced by Vin Diesel; beautiful, conflicted warrior Gamora, played by Zoe Saldana (claiming her third giant franchise; is she our current record-holder?); and musclebound, humorless, vengeful Drax the Destroyer, played by wrestling star Dave Bautista.

The film jumps between galaxies and planets and interstellar colonies with amazing proficiency. Director James Gunn, who co-wrote the script with Nicole Perlman, has a rare talent, one that George Lucas also had but few filmmakers working in this genre do: He can effortlessly cut between evocative worlds we’ve never seen before without losing sight of the action and the pace of his narrative. With a few deft strokes, he can place us inside an entire mining colony built around the decaying head of an ancient deity floating around the cosmos — the same way that Lucas and his directors could throw us from a swamp planet to Cloud City without having to sit around and give us belabored explanations of what these were. This is a precious gift: an intuitive ability to understand both what we need to know and what we don’t need to know. A story of this scale needs elegant shorthand, the kind of shorthand whose very lack doomed films like John Carter and After Earth. Gunn has it in spades.

A good thing, too, because the plot itself is ridiculously — and, I suspect, purposefully — dense, having to do with something called an “Infinity Stone,” which apparently has the power to destroy entire galaxies when wielded by the right being. Or something. Again, it doesn’t really matter. This might be, in terms of sheer destructive capability, the most powerful MacGuffin in the Marvel universe, and yet it feels thoroughly inconsequential. That’s because this is an insistently lighthearted movie. Think about it: Whereas most action films would have a character designated as comic relief, Guardians has a character designated as straight-man relief. Practically everyone else is comic relief of one form or another.

And so, the film eagerly delivers a nonstop onslaught of irreverent one-liners and jokey exchanges and random pop-culture references — endearing gags you want to laugh at even when they’re not particularly funny. Context is everything here. Consider a line like, “He says he’s an A-hole, but — and I’m quoting him here — he’s ‘not 100 percent a dick.’” Or: “I come from a planet of outlaws. Billy the Kid. Bonnie and Clyde. John Stamos.” These wouldn’t be particularly brilliant lines in a standard-issue comedy. (Really? More Stamos jokes?) But wedged inside a superhero spectacle set in outer space, it all feels hilarious, the same way the familiar classic-rock soundtrack, featuring everything from “Moonage Daydream” to “Cherry Bomb,” feels cool. The movie wins you over with its calculated incongruities. It has a charm similar to this year’s earlier The Lego Movie, but that film used its wild, relentless gags to build to a celebration of unbridled creativity and diversity, and even managed to question things like fate, faith, and free will.

But in Guardians of the Galaxy, they’re mostly just jokes. And that frivolity might be both the film’s greatest asset and its chief limitation. Gunn occasionally gives us moments that suggest he wants to do more than just make us chuckle. He has a great eye, not necessarily for pretty pictures, but for images of emotional grandeur — whether it’s of a spaceship beaming in two doomed lovers floating in what appears to be a final embrace, or for the spectacle of thousands of tiny ships conjoining to create a kind of protective cosmic netting. But he almost always undercuts these moments with gags, as if he’s afraid to commit to something bigger, darker, more profound. The film seems forever on the verge of becoming transcendent, but something keeps pulling it back — a certain eager-to-please-ness, maybe even an almost adolescent fear of the grand gesture.

Gunn originally came up through the ranks at Troma (where he wrote Tromeo and Juliet), and a friend I saw Guardians of the Galaxy with, who loved the movie, called it “the most expensive Troma film ever made.” That sounds about right, and it’s not a bad thing. The film seems content to be the class clown of the Marvel Universe, which is all well and good. But like most class clowns, sometimes you wish it would apply itself — because it seems capable of being so much more.