This morning news broke of the death of Rick Smith, the famed makeup artist behind The Exorcist, Little Big Man, The Godfather, Taxi Driver, and Amadeus. We spoke to director Guillermo del Toro, a close friend and colleague of Smith’s, and condensed and edited his comments into this as-told-to piece.

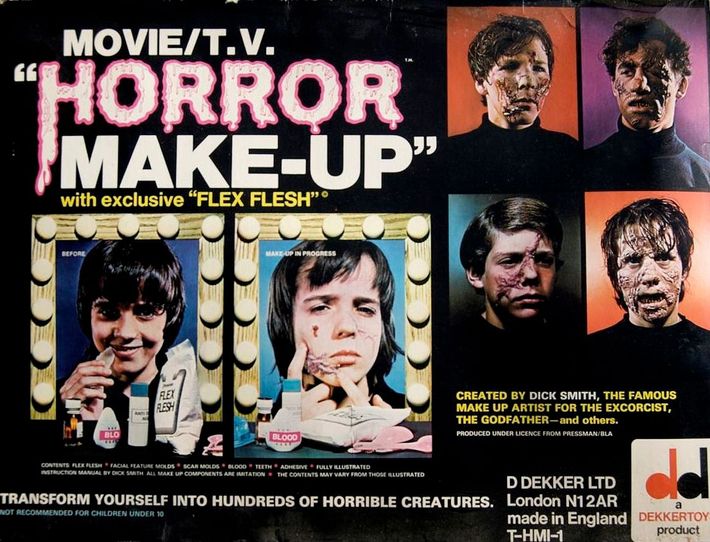

Without Dick Smith, I would not be making movies. He was my mentor. The first time I came into contact with him was as a child. When The Exorcist came out, I bought his makeup kit (below) in a toy store. It came with gelatin and molds and colors, and I did my own makeup effects at a very young age. It wasn’t until later that I actually wrote to Dick, explaining to him how much I needed to take his makeup-effects course because no one in Mexico was going to help me do effects for my first feature, Cronos. I said, “I cannot afford an American makeup effects artist. I have to sculpt, paint, design — I have to do everything myself!”

I finally met him in about 1987. I applied for the course and we met in New York. And he greeted me like he had known me for decades, he was so incredibly open and nice. He had dinner with my father and my mother and me and my wife, who was then my girlfriend. Dick came to be like part of my family. He was a guy that changed the way I see the art of making movies. He wanted to spread the gospel, the knowledge, amongst colleagues and amongst anyone who was interested in learning. Dick had a way of welcoming anyone new without prejudice or snobbery.

To this day, many of the principles that he taught me, I still apply to my own creations. Dick always said, “strive for realism.” So don’t strive to make a monster a monster. Don’t do an old-age makeup that is an old-age makeup. Try to actually create the face of an old man, a real old man, which is what he did with Dustin Hoffman in Little Big Man and F. Murray Abraham in Amadeus. Don’t go for the effect; go for the reality. And that’s as true for a monster as it is for a piece of delicate prosthetic makeup. He also told me never to sculpt an expression into a piece of prosthetic. Many artists sculpt something that is already angry or screaming, and they exaggerate the facial lines of expression. He said not to do that, but rather to always sculpt the face in repose. That way you could let the actor imbue the prosthetic with his own character.

Sometimes I would go to New York and I would take a commuter train to Larchmont and spend the day with him. We’d be together the entire day, from morning, through lunch, until dinner, and then I would take the train back to Manhattan. We talked so much. And we wrote each other often. I have dozen and dozens of letters, from over the years, in which he would respond to every one of my photographs and drawings telling me what was wrong and what was right, so that I could continue learning. And that was a gift. He was willing to talk to anyone who wanted to know more about his craft. He changed not only my life, but the lives of hundreds of artists.