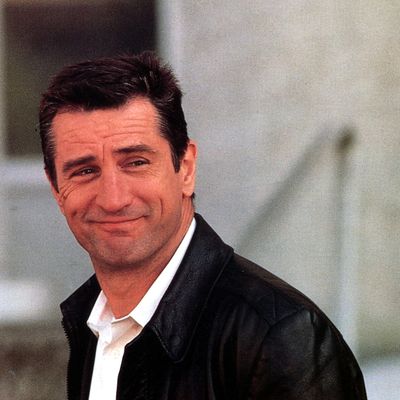

Film critic Glenn Kenny’s entry in Phaidon/Cahiers Du Cinema’s Anatomy of an Actor book series looks at ten key Robert De Niro roles, including the one that helped moved him from big-A Actor to movie star. In this excerpt from Kenny’s book, on sale today, he looks at Midnight Run.

In 1975, when Robert De Niro was shooting Taxi Driver, the actor’s then-agent Harry Ufland told a journalist, “Bob will never be a movie star. He is an actor. He is just not seduced by glamour.” By the middle of the 1980s, Ufland’s prediction was still holding true. In its November 1988 issue, the New York–centric humor/satire magazine Spy published a piece titled “The Unstoppables,” which outlined how the most talked-about actors in the culture were, by and large, not people who made movies that made a lot of money; hence, not “movie stars.” De Niro was pretty much “Exhibit A” for the case put forth by writers Rod Granger and Doris Toumarkine, which was that filmmakers who didn’t succeed at providing a good return on investment needed to be punished.

By that time, the spirit of the ostensibly maverick ‘70s was long past. Where De Niro fit into a new mode of mainstream filmmaking had yet to be determined. His first foray into middle of the road movies was 1988’s Midnight Run, a crime picture/buddy comedy of the sort refined by the 1982 picture 48 Hours. The hook in this sort of picture (1987’s Lethal Weapon is another) is that the buddies start off as antagonists and arrive at a rapprochement that’s supposed to delight the audience. It’s Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple with guns.

De Niro plays Jack Walsh, a hard-bitten ex-cop and largely down-on-his-luck bounty hunter who is looking to get out of this rotten business and open a coffee shop, if only he could make one big (and, of course, last) score. Such a score is dangled before him by a weasel-like bail bondsman, and soon Walsh has picked up Jonathan “The Duke” Mardukas, a mild-mannered accountant who’s absconded with millions in mob money and donated it to charity. Everybody wants “The Duke,” as it happens: the Mob, the Feds, a rival bounty hunter, and so on. Beneath Mardukas’s mild manner is a shrewd persnickety side that immediately abrades Walsh’s streetwise bearing.

The role of Mardukas was played by Charles Grodin. Their match-up is the most inspired feature of the movie. The rapport between the two lead performers suffices to keep the viewer engaged despite the fact that the movie is overstuffed with scenes that really don’t serve a dramatically legitimate purpose — apparently at the behest of director Martin Brest, who, fresh from the success of 1984’s Beverly Hills Cop brought car chases, prop-plane thefts, and helicopter pursuits into what had been mostly a train-and-autos trek.

Watching De Niro in this picture with a consciousness of the movie’s context at the time of its release is odd because there’s a sense of a retread involved. De Niro is now in a mainstream movie that’s highly informed by the tough-guy tropes that he and Martin Scorsese pioneered in the ‘70s. And as he’ll do more explicitly in his performances in mobster or cop roles after the turn of the century (like Analyze That and Righteous Kill, his ill-advised 2008 reunion with Al Pacino), he ever-so-slightly mocks those conventions in Midnight Run. What makes Walsh interesting, if he’s interesting at all, is that he’s being played by De Niro. But while this was the first really ordinary genre picture De Niro worked in as De Niro the Protean Actor, Hollywood by this time was full of actors who aspired to De Niro’s status, acting in precisely these sorts of films. So, at times in Midnight Run, there are instances when De Niro’s application of his own unique talents to the project yields results that look strangely secondhand.

It was during the shooting of one of these scenes that De Niro received a taste of his own improvisational medicine, which had genuinely discomfited such past co-stars as Joe Pesci and Jerry Lewis. Here’s an account from an item in the New York Times: “It was understood that Mr. Grodin might have some opportunity to improvise. The ‘night boxcar scene,’ as Mr. Grodin calls it, was, he said, improvised entirely. The situation begins with Mr. Grodin as Mardukas shutting a boxcar door in Mr. De Niro’s face in an effort to escape him. Mr. De Niro, in the role of Jack Walsh, promptly boards the car from the other side — enraged. But, Mr. Grodin said of the scene, ‘We knew it had to end with De Niro revealing something personal about himself’ — the history of a wristwatch that has sentimental value. ‘How do you get to that point in a couple of minutes where he’s going to reveal himself? What do you say?’ Mr. Grodin went back to his motel and wrote down about 15 lines he thought might change the mood of Mr. De Niro, who tends to stay enraged when he becomes enraged. Back to the boxcar, with a crew of about 40 people looking on: comes the crucial moment. Mr. Grodin tries line No. 1: ‘When you get your money for turning me in, you might want to spend some on your wardrobe.’ ‘Not a glimmer of a smile,’ said Mr. Grodin. ‘Nothing. [Director Martin] Brest comes over: ‘I love you. You’ve got to find a way.’ ‘It took me ten days to get ready for Take 1,’ Mr. Grodin said. ‘All those people in the boxcar. It was a tough situation. Out of desperation I said, ‘What could I say to Robert De Niro to get him off the mood he was in?’ That’s when, on Take 2, I asked him if he’d ever had sex with an animal.’ Mr. De Niro’s reaction is on the screen.”

Midnight Run achieved the aim of rendering De Niro bankable. The Spy article that cited De Niro as an “Unstoppable” noted, with no traces of coyness, that it was not able to cite “final rental figures for recent releases such as Robert De Niro’s Midnight Run.” Truth to tell, it did not need to; the movie’s opening weekend put a substantial chink in the authors’ premise. “The movie … racked up $5,518,890 its first weekend in release, putting it among the nation’s top five box office hits — a select group De Niro rarely inhabits (its returns are already more than the total grosses of such De Niro films as Falling in Love and True Confessions),” reported Harry Haun in the New York Daily News. From this point forward, De Niro would be unstoppable in a new and different way.