“There’s something comic about the nice guy in the Apocalypse,” says Tom Perrotta, describing the hero small-town mayor of his 2011 novel, The Leftovers. “He wants people to be happy. He’s ill suited for this world that he’s living in” — a suburb torn apart by a “Rapture-like phenomenon.” “But he’s also the right man.”

He wasn’t the right man for HBO’s new cable adaptation of the book, co-created by Perrotta and Lost’s Damon Lindelof, which transforms the mayor into a cable-ready anti-hero. But that kind of switch is nothing new for Perrotta, who has been accommodating the imperatives of screen adaptation for two decades, becoming one of Hollywood’s most prominent literary-novelist screenwriters in the course of what he calls “the systematic exploitation of my work.” It pays better than teaching, he says, but there are costs—projects dying inexplicably; questions about his literary bona fides, which he admits “have bothered me.” But he can’t complain. “I’ve managed to have a career, have an audience, and it’s not like I’m completely dismissed. I almost didn’t have a career at all.”

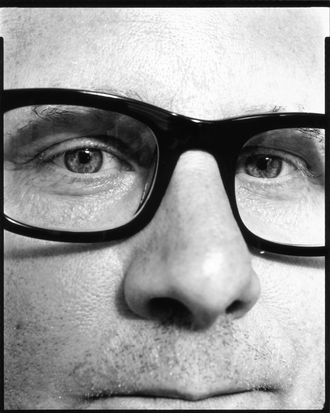

At the moment, he’s enjoying a cup of black coffee on the screened-in porch of his family’s gray-shingled five-bedroom house. Perrotta, whose default expression is a slight smile, is short and, for a 52-year-old writer, surprisingly well built—he looks like a hip gym teacher who’s swiped the glasses off an architect. Just beyond his yard, a string of traffic snakes up into Belmont Hill (Mitt Romney’s former neighborhood, ten miles northwest of Boston), which still embodies that antiquated phrase “bedroom community”—a place more alive in the books Perrotta writes and the work he admires, from Updike to Mad Men, than in real-world strip-malled, subdivided America. It’s also surprisingly well stocked with tenured professors.

It was Harvard, where Perrotta once taught composition, that drew his family to the area (he was an adjunct, “which can be hard on one’s dignity”). But it was the royalties from his best-selling novel Little Children, a tragicomic chronicle of parents behaving badly in a town called Bellington, that bought this house. He quit teaching more than a decade ago in favor of a more lucrative sideline. When he commutes now, it isn’t to Cambridge but to L.A.

Perrotta has sold film rights to all six of his novels and one of two story collections, and he’s had a hand in every adapted screenplay but one (Alexander Payne’s iconic Election).

It all began, oddly, at a literary retreat. In 1995, Perrotta became a fellow at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference on the strength of his debut story collection, Bad Haircut. He read there from a novel-in-progress, The Wishbones, a coming-of-age comedy about a wedding-band guitarist who refuses to grow up. Another writer there was impressed enough to call up two young producer friends, Ron Yerxa and Albert Berger, who then cold-called Perrotta. He regretted to inform them that The Wishbones was far from done. But then he had an idea.

“I was not actively trying to sell myself,” says Perrotta, “but I was still very resentful that Election hadn’t made it out of my drawer. And it just popped into my head: I’ve got these producers on the line! Let’s just see if they’ll read it.”

Election the novel was finally published just a year before MTV Films released Payne’s indelible black comedy—a rare case of a publisher following a film studio’s lead. An executive had asked Perrotta, “You don’t want to write the screenplay, do you?” Of course not, Perrotta reassured him. He didn’t know how—not yet. But after Payne’s movie caught on with young Hollywood, studios came after everyone involved with the project. “They would go down the list” of people involved with the movie, Perrotta says, “and get to me.” The WB network hired him to write two pilots. He adapted another of his unpublished books, Lucky Winners, on his own and, more promisingly, collaborated with Frasier vet Rob Greenberg on a Freaks and Geeks–style treatment of Bad Haircut. “We had a great time,” he says, “but the cable revolution hadn’t happened yet, and Bad Haircut was R-rated material. The creative people said, ‘Don’t worry about it, we’ll push the envelope.’ But you realized that wasn’t really gonna happen.” Still, the deal paid him three times his Harvard salary.

Perrotta says he loved teaching (he liked ghostwriting a YA horror story a little less). But he also had a family, and he wanted to write full time. “I started to become much more flexible,” he says. “It’s probably the kind of thing that makes the young actress get into porn.”

Trying to turn The Wishbones into a film—a two-decade process Variety honored with the shorthand “Development Hell”—was both demoralizing and lucrative. “My agent called and said, ‘There are 16 interested buyers.’ And then came the news that Adam Sandler had a competing project, and then 14 interested buyers dropped away.” Fox picked it up anyway, and Matt Damon and Ben Affleck wrote a draft; Noah Baumbach also took a crack. But post–Wedding Singer, Fox let its option expire, and it went to New Line Cinema, where Perrotta wrote a fresh draft. New Line let it drop, only to pick it up again in 2008—only to drop it again. Showtime optioned it in 2010, and Perrotta wrote a pilot. “So that was the fourth. And what stage is that in? Dead.” But all those options were “still more money than I had made on anything. It went from being a frustrating thing to an insurance policy.” Did the ordeal influence him to have Adam Sandler raptured in The Leftovers? “No comment!”

Joe College, Perrotta’s most autobiographical novel, also died in development—and he worries he may have embellished it with an unnecessary “Mafia subplot” in order to gin up Hollywood interest. “Was that organically generated,” he asks, “or was that me writing to some movie reality?” His great success as a co-writer came with a much trickier novel (“Nothing will kill a story like a pedophile”): Little Children. Director Todd Field played up the tension of a story about parents embarking on an affair while a sex offender lurks in their midst. “People say he’s an acute social observer, which is true,” says Yerxa, who, with Berger, also produced this adaptation. “But he’s also an observer of the understated, underseen warfare,” the “stark conflict that comes out from a very calm sea” of American suburbia. Berger sees his volatile mix of the tragic and comic as irresistibly adaptable. “Tom’s writing,” he says, “is very, very elastic.”

The elasticity gives filmmakers a lot to play with—but then, inevitably, they carve out the ambiguities. Election was crafted into farce, Little Children into a thriller. “It wasn’t so much that [Little Children] took a serious turn as that it got purified by Todd’s sensibility,” says Perrotta. The movie, starring Kate Winslet and Patrick Wilson, was largely faithful to its source. But as it barrels toward an ending more melodramatic than the book’s (when Perrotta first heard about it, he thought Field was joking), the humor fades. “A lot of the comic material” in the overlong script “ended up on the editing-room floor,” says Perrotta. “One of the reasons that I gravitated toward TV was that you are a producer, and you do get to follow the process all the way through.”

With The Leftovers, HBO execs have given almost unprecedented influence to Perrotta—input in writing, casting, and editing. But the first thing they suggested after signing it up was bringing on an experienced showrunner; Lindelof was high on their list. “I was intimidated,” says Lindelof. “I just got it in my head that he was going to have a Salman Rushdie–esque bearing about him. HBO said, ‘You’re gonna love him, trust us.’ ” When Perrotta came into his office, Lindelof felt “that animal-pheromonal thing the minute you meet someone new.” They’d grown up 30 minutes apart in New Jersey. “He’s the sweetest, most personable human being ever.”

Their first draft of the pilot, however amicably co-written, didn’t satisfy HBO. “It wasn’t propulsive,” says Michael Lombardo, the head of programming. “It retained too much of its meditative quality.” Perrotta remembers one “strong note”: “We have a main character who is maybe a little too nice, a little bit too marginal.” Lindelof recalls “specifically discussing the word anti-hero, which Tom and I resisted. They said, ‘The anti-hero is the new hero. He has to be flawed.’ ”

Lindelof came up with the idea of transforming Kevin Garvey from Mapleton’s nice-guy mayor into its possibly delusional, feral-dog-shooting police chief. When Lindelof told the execs, “they just lit up,” he says. Perrotta understood the need for the change—and besides, if they hadn’t come up with a solution, “the show wouldn’t have been made. So the question for the writer is, is this the sword you’re gonna fall on?” His only red line, when he thinks about it now, would have been their insistence on explaining the “Sudden Departure.” To hear Lindelof tell it, a big reveal seems unlikely. “If that’s why you’re watching the show, don’t watch the show.”

Perrotta describes “the defining creative tension” between him and Lindelof as the question of whether supernatural events can happen in Mapleton. Already there’s someone called the Mystery Man (drawn from a very minor character in the book) who may be a hallucination—or a specter. Perrotta has argued that the Departure was the kind of “foundational supernatural act” on which all religions rely, while “history is humans grinding it out in the non-miraculous world.” Lindelof felt that “the rules seem different now.” The first season remains ambiguous enough to keep both partners happy, and Perrotta lapses into Zen-like language when he talks about walking that line: “There’s kind of a letting go,” he says. “You have to surrender.”

Halfway into our interview, Perrotta’s 17-year-old son enters the house. He’s shirtless, with a perfect six-pack. “Hey, Luke,” says Perrotta. “How was the beach?”

“Beach was good. Boxing was rough.” He looks at me. “He won’t let me fight.”

“We don’t want his head to be beaten,” says Perrotta, who lets his son spar but not compete. “Our daughter, who’s in college, does jujitsu and karate. He said, ‘I want to learn to box.’ ” Perrotta played football through early high school. “My brother was the real football star, and I couldn’t compete with him, so I went down the bohemian path.”

Early on, Perrotta was seen as a Jersey writer, his amiable male wit compared to Nick Hornby’s (“Mildly elitist,” he calls himself). Joe College anatomized his college-age feeling of being torn between working-class home and Yale. Now he knows Yale won: “Once you’ve been to an Ivy League school, you’ve been Ivy League–ized. It doesn’t mean you consciously leave things behind; you’re just rendered unfit for them.”

Then again, Perrotta’s daughter is a comp-lit major at Brown, and she doesn’t read nearly as much as he did, he says. “We’re just living through a revolution,” he tells me. “This is my TED talk now,” he laughs. “I didn’t really know people who wanted to be screenwriters. Now if you go to an Ivy League university, the kids who want to be writers want to be screenwriters. I took German film and French film in college. But when I got onto a film set, it was like, Oh, if I’d only known, maybe I could have done this in my early 20s.”

In writing The Leftovers, Perrotta was intent on “undermining the apocalyptic genre” with the intimacy of domestic fiction, he says. “But in moments of hubris I thought, I’m sure there’s this amazing David Mitchell version of this novel which would take place in four different cultures. But I’m not able to write that story.” And when he collaborates with Lindelof, inventor of violent, supernatural allegories, “I envy the freedom that he seems to have as a writer.”

The writers’ room feels like the site of his provisional, possibly temporary liberation. “I just want to be freer and a little less methodical if possible,” he says. He might want to try other genres, like a crime novel—“or do something new with a Hollywood novel—that’s an interesting challenge.” I ask if the writers’ room is also literary research, and he says of course it is, in the same way that taking his kids to the playground was “research” for Little Children. It’s one way to get out of the suburbs.

*This article appears in the July 14, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.