Network TV these days is often used not as a descriptor, but as an epithet: “Oh, that show’s not bad for network TV.” “I can’t believe they gave all those Emmy Awards to network TV shows.” “Who cares about the new fall shows on network TV? When does The Walking Dead come back?” As another television season gets underway this month, broadcast TV finds itself diminished, still enormously profitable, still possessing big hits — and yet struggling to stay culturally relevant in a world where programming choices have become seemingly limitless and platforms of distribution dizzyingly diverse. The Big Four networks — ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox — are hardly dead, and they might not even be dying. They have, however, become shadows of their former selves, gods of the media universe now made flesh. It was not always thus, of course. In fact, it’s not hard to make the case that we’re not far removed from a golden age of network television that rivaled the much-acclaimed run premium cable has been enjoying in recent years.

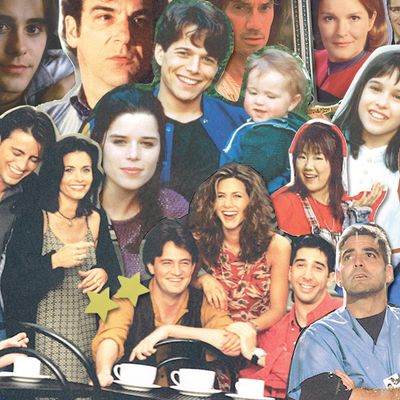

This month marks the 20th anniversary of the start of what we now recognize as one of network TV’s watershed seasons, an epic year that is most easily remembered for the debut of NBC’s twin Thursday night triumphs, Friends and ER. And over the next four days, Vulture will look back at those Peacock powerhouses, revisit the 1994-95 season’s best episodes and moments (as well as some of the worst), and revel in other phenomena from that banner year of TV: the dizzingly outrageous plot twists of the Fox hits Melrose Place and Beverly Hills, 90210; the launch of Party of Five; the tumultuous season of Saturday Night Live; the mania surrounding George Clooney; and, of course, the still underrated, canceled-too-soon ABC drama My So-Called Life.

But beyond birthing seminal shows and turning Clooney, Claire Danes, and Jennifer Aniston into household names, the 1994-95 TV season was notable for numerous other milestones. Fox added Sunday football to its lineup, stole away some of its rivals’ best affiliates, and became a serious player. UPN and the WB were born, stealing millions of young viewers away from the big nets and foreshadowing the current era of audience fragmentation. And TV (at least temporarily) became a more diverse place with a slew of shows featuring African-, Hispanic-, and Asian-American leads. While you can’t call 1994-95 the last blockbuster network TV season — 2000-01 would see the debut of monster hit CSI wedged between the massive first two seasons of Survivor — it was absolutely a major inflection point for broadcasters. The business model the networks had made billions from over the decades was starting to show serious signs of stress, and not just from within: 1994 was the year that DirecTV debuted; that FX, IFC, HGTV, and other still thriving cable networks launched; and that Netscape Navigator, Amazon, and Yahoo! all arrived. But at the moment this landmark season began, the broadcast networks were still very much near the top of their game, still behemoths. Consider: The George Wendt Show, a terrible sitcom starring the former Cheers regular, was canceled after just six episodes in the spring of 1995 because its average audience of 10.4 million viewers was deemed to be disastrous. Last season, the NBC smash The Blacklist pulled in an average of 10.8 million viewers before its DVR audience was tallied, and NBC heralded the show as its biggest first-year drama hit since … ER.

While it’s no shocker that broadcast TV ratings aren’t what they used to be, the stark decline of the Big Four’s monopoly on audiences becomes shockingly clear when you juxtapose ratings from the 1994-95 season with those of today. To understand the depth of the drop-off, check out the graphic below: It lists the Nielsen rankings for every regularly scheduled scripted series that aired during the 1994-95 season as measured in adults 18-49 ratings, only with a few big broadcast shows from the 2013-14 season mixed in with the 20-year-old data. Needless to say, the comparisons aren’t pretty. The Big Bang Theory, last season’s No. 1 scripted show in the key demo, would have ranked No. 57 in 1994-95, just above Sister, Sister. (And check out where Emmy darling and ratings-driver Modern Family would have fallen: 90th place, between M.A.N.T.I.S. and Mommies (and even more tellingly, Law & Order: SVU would rank 103rd, betweeen UPN launch fodder Platypus Man and Pigsty.)*

In addition to being bigger and broader than cable that year — a claim the networks can still make today, albeit much more tenuously and not in every time period — broadcast TV outshined its cable cousins in terms of reputation. Today, save for the rare gems (e.g., The Good Wife, Parenthood), we expect the Big Four networks to churn out populist, popcorn programming; the really groundbreaking stuff, it is often said, can be found on cable (and, increasingly, streaming outlets such as Netflix and Amazon). Not so in 1994. Yes, exceptions could be found on cable as the network season got underway in late August of that year — HBO’s The Larry Sanders Show was in its prime; Cartoon Network was in its first season of Space Ghost Coast to Coast; Comedy Central had recently brought Absolutely Fabulous to our shores and was still airing Mystery Science Theater 3000; and Nickelodeon would soon introduce its young audiences to the joys of The Secret Life of Alex Mack and All That. But for the most part, subscription-based TV was still mostly known for addictive non-fiction programming (The Real World, SportsCenter), pure cheese (USA’s Silk Stalkings and Weird Science; Lifetime’s many made-for-TV movies), and reruns of shows that used to air on network TV. In 1994, most of what was good about TV — most of what we loved — could be found on channels that didn’t require a $100-plus cable bill or an Internet connection:

—ER, Friends and NewsRadio joined an NBC lineup already lousy with future classics (Seinfeld, Frasier, Homicide: Life on the Street, Law & Order) and shows which remain beloved (The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Blossom, Mad About You, Sisters). Conan O’Brien, in his second season hosting Late Night, was struggling in the ratings, but was emerging as a Gen X darling and laying the groundwork for what would become a long TV career.

—Though the Peacock was getting ready to dethrone it, ABC remained a ratings giant thanks to its Tuesday and Wednesday lineups of mass-appeal comedies, which included Roseanne, Home Improvement and Full House, not to mention a well-stocked stable of interchangeable TGIF half-hours (Boy Meets World, Family Matters). The Alphabet network also went into the season with TV’s hottest drama, Steven Bochco’s sophomore hit NYPD Blue, which scandalized social conservatives with its naughty words and bare butts even as its shaky-cam style changed the way TV dramas were filmed. The 1994-’95 season proved Blue was no rookie fluke: David Caruso famously quit the series early in season two, but the ratings (and critical acclaim) just went higher. ABC also gave us My So-Called Life that year, but sadly never knew what to do with it.

—Fox had a banner year as well, starting with its shift of The Simpsons back to Sundays to take advantage of its new NFL franchise (we’re pretty sure that move worked out). On Mondays, Melrose Place settled in for a long run on Mondays and brought viewers to a newcomer that would end up one of the network’s best shows ever, Party of Five, while The X-Files began its climb from cult fave to mainstream hit in its second season on Fridays.

— CBS, then known mostly as a network for old folks (Murder, She Wrote was in its tenth season), nonetheless possessed carry-over hits of its own: Murphy Brown, Northern Exposure, and The Nanny. During the 1994-95 season, it added the treacly but ultimately iconic Touched by an Angel to its roster as well as David E. Kelley’s medical drama Chicago Hope (Mandy Patinkin, holler!). And perhaps most importantly, CBS had Dave Letterman, whose new Late Show was, for a moment at least, trouncing Jay Leno’s The Tonight Show in both ratings and buzz. (Sadly, it wouldn’t last.)

—In addition to weekly series, the broadcast networks were also still very much in the business of creating big events: made-for-TV movies every week and blockbuster miniseries during the so-called “sweeps” months of November, February, and May. The 1994-95 season wasn’t a watershed year for quality pics — Scarlett, a sequel to Gone with the Wind, was a total dud — but many millions still tuned in every week to watch Tori Spelling, Melissa Gilbert, or Meredith Baxter face their demons for two hours. The form was so strong (or weak, depending on how you choose to look at these things) that, in October 1994, there were not one but two quickie biopics about Roseanne Barr.

—Broadcast networks and local stations alike were still able to draw huge audiences outside of primetime in 1994-95. This was a golden age for daytime talk shows, when Oprah, Sally, Maury, Jerry, and Geraldo were at the peak of their powers (for better or worse). Soap operas, now on life support, were thriving back then: ABC, CBS, and NBC collectively aired ten daily sudsers, compared to just four today. (Danger was just around the corner, however: Live coverage of the O.J. Simpson trial in 1995 frequently preempted the daytime dramas, disrupting viewing habits, and, as some observers see it, helping speed along the genre’s decline.) While Star Trek: The Next Generation had concluded its influential run the previous May, spinoff Deep Space Nine was still going strong in syndication, and fantasy fans welcomed Hercules in January 1995 (which introduced us to future sensation Xena during its first season as well). And in late night, Arsenio Hall wrapped up his successful syndicated series while a pre–Daily Show Jon Stewart tried (but failed) to take his MTV show to a larger platform in syndication.

As amazing as the 1994-95 season seems in retrospect, TV-industry observers at the time were decidedly down on the year’s newcomers. Newsweek TV critic Rick Marin, writing in the magazine’s fall preview, said, “no one is particularly stoked about 1994-95,” and called it “the hitless season … the safe season … the season whose most exciting programming information is Dabney Coleman.” Veteran industry analyst Betsy Frank of Saatchi & Saatchi Advertising, interviewed by the Associated Press, bemoaned the fact that the networks had approached the year “with more stability and more conservatism than one would hope.” (Indeed, per Frank’s calculations, the four nets went into the fall planning to debut just 27 new shows, down from 38 the season before.) Another wag could barely contain his disdain for what was on tap in 1994-95. “Looking forward to another exciting fall season of new and innovative television programming? Don’t,” he snarked in a Washington, D.C., daily. “The season is shaping up to be a major disappointment for couch potatoes in search of new video addictions.” The moron who wrote that was … me. I was a newbie TV critic then, two years out of college and filled with radical ideas — such as the notion that Friends was one of the worst comedies NBC had put on Thursdays in a decade. In my defense, the pilot for Friends really wasn’t that good (even test audiences weren’t impressed by it), and I did correctly predict that ER would triumph over Chicago Hope.

In any case, it’s much easier to remember TV’s past fondly than it is to make predictions about its future. So kick back with your 1994-appropriate Zimas in hand and your Color Me Badd Pavement blasting forth through the headphones connected to your newfangled portable CD players, and join us all week (and then from time to time throughout this upcoming season of television) as we shine our brightest spotlight on the awesome, influential, underrated, and ridiculous gifts that the 1994-95 network TV season provided. First up: Vulture editor Margaret Lyons ranks the season’s 100 best episodes.

* A word about methodology: Our chart uses adults 18-49 ratings rather than total viewers for a couple of reasons. First, networks and advertisers were rapidly embracing the 18-to-49 demo as the key measure of success by 1995; even CBS, ever the old folks’ network, told the press in March 1995 that it was planning to make over its struggling lineup with shows targeted to the young (ergo Central Park West). And since networks today still stress adults under 50, it makes sense to compare apples to apples. Secondly, total viewer figures don’t fully capture the extent of audience erosion because U.S. population growth since 1994 means there are about 50 million more potential eyeballs for shows today (around 317 million) than two decades ago (263 million). By contrast, a ratings point is a constant measure: Each point represents a percentage of the adults-18-49 viewing population at the time. And to keep things as fair as possible, the data cited for the 2013-14 season are so-called “live plus same-day” numbers rather than the “live plus seven” ratings you usually see cited by networks and media outlets when they’re talking about seasonal averages for shows. The latter metric produces a bigger rating, since it tallies up audiences who watch a program via DVR up to a week after it first airs. But in 1994, there were no DVRs (and Nielsen didn’t regularly measure folks who taped a show with a VCR). Still, even our chart gives current shows a bit of an advantage, since “live plus same-day” ratings do count anyone who watches via DVR the same day a show airs — something that would not have counted in those simpler days.