The photographer Garry Winogrand had night vision. With it he saw not only the dark side of his own time in America, he saw the first flickering of our hopelessly polarized and fissuring futureÔÇöits paranoia, rage, and blind righteousness. Winogrand, who was born in 1928, took his first picture when he was 20 years old and never really put down the camera again. And I mean never. He moved like a meteor from city to city, neighborhood to neighborhood, returning to the same sites, always finding people devoured by desire, resignation, and nonbeing. He called himself ÔÇ£a gypsy.ÔÇØ Winogrand peered through the mist of changing America, saw brittle invalids, rich guys with rheumy eyes, figures acting prescribed parts, people frozen in hatred like the plaster figures in Pompeii. His pictures startle with their rawness. Almost always close in to his subjects, heÔÇÖs aggressive. By the end of his life, he was shooting so incessantly he wouldnÔÇÖt even take the time to develop his negatives, much less make prints from them. ÔÇ£I sometimes think IÔÇÖm a mechanic,ÔÇØ he said. ÔÇ£I just take pictures.ÔÇØ In those years, he nearly stopped editing, or even looking at, his work. Other people did his printing and put his books and shows together. He died, too, with the same headlong drive. Diagnosed with cancer in January 1984, he went immediately to Tijuana to seek an alternative cure and was dead two months later. He was only 56.

WinograndÔÇÖs indelible vision is the subject of a powerful retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Densely installed and spilling out of four galleries, it consists of more than 175 of the artistÔÇÖs imagesÔÇömore pictures of his than IÔÇÖve ever seen at once, and they left me wanting more. This sweeping, soup-to-nuts show begins with a 1950 picture: a lone sailor carrying a suitcase walking on a dark New York street. ItÔÇÖs a perfect metaphor for America right after World War II, embarking on what turned out to be a one-decade ÔÇ£American Century,ÔÇØ beginning to experience existential stirrings and mysterious chafing against cultural values. Subsequent images let us see approaching catharsis, rebellion, reactionary attitudes setting in psychic stone. Stylish women openly smoke on New York avenues, as was once taboo; theyÔÇÖre eyed disapprovingly and wantonly by men. Cigar-champing campaigners for Richard NixonÔÇÖs failed 1960 campaign form a psychological palimpsest of a mounting resistance to change. Liberations of all kinds come into focus: pictures of women, blacks, Hispanics, uncloseted gay culture, and a free-for-all of conservative businessmen, construction workers, and military personnel turning cold cheeks to a shifting society.

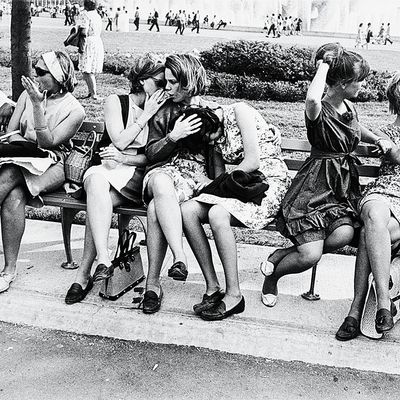

The dam breaks in the next gallery. From around 1960 to 1970, Winogrand devoured a country as it came unmoored, grew confused, slipped into chaos, convulsing and becoming freer. Winogrand is an oracle of unease, seeing tourists in Dealey Plaza yearning for proof of truths and conspiracies; a kid wearing Mouseketeer ears with his camera-toting parents in L.A.ÔÇÖs Forest Lawn cemetery. Women in miniskirts, in tight sweaters, finding sisterhood in public, wearing what they want to wear, acting any way they wish. WinograndÔÇÖs pictures of women often arouse nettled responses. I adore them, but thereÔÇÖs no doubt that this is an artist seeing female bodies not only as agents of change but as objects of his delectation. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm still compulsively interested in women,ÔÇØ he said.

Winogrand gets one aspect of the sixties better than any other photographer: the visible divide of contempt of one half of America for another half. Nowadays, visual evidence of oneÔÇÖs political persuasion is blurred, almost gone. Fox News guests sport goatees, and the hosts talk to Ted Nugent. In WinograndÔÇÖs world you donÔÇÖt need a weatherman to know which way the political wind blows. Construction workers bellow at long-haired protesters; everyone peers with hatred at youth. A telling picture from 1969 pictures what looks like a family of out-of-towners dumbstruck at the hippies in Central Park. The world opens in the divide between themÔÇöa divide that turns cosmic in the ÔÇÖ70s pictures. Everyone turns into his or her own fun-loving or cloistered cathedral.

The show also incorporates 56 prints made after WinograndÔÇÖs death. These images were taken from thousands of proof sheets and those rolls of film he never developed. Many consider the sizing and making of these prints a betrayal of his art, and IÔÇÖm happy that there are those so fastidiously looking after his legacy. However, IÔÇÖm happier to see these posthumous prints. Each is printed larger than his other work (to clearly distinguish it), and marked as posthumous work. ThatÔÇÖs good enough for me. They exist; they ought to be seen.

Many also claim that these late pictures show a falling-off. I disagree. They, too, follow America in these years: the way places went from being concentrated to being bland, full of burnouts and lost souls riding on packed airplanes. These late pictures complete WinograndÔÇÖs atlas of America, his cosmology of the inner life of a country turning inside out, twisting into half-beast, turning back, creating nests of new beings.

Something weÔÇÖve been missing also becomes evident here. The whole world is now filled with incredible imagesÔÇöespecially on Instagram and other social networksÔÇöthat owe something to WinograndÔÇÖs, documenting life, change, and all the rest. Yet the art world and museums are not. Instead they tend to show oversize, very still pictures or images that investigate formal properties and ideas of display and presentation. I love many of those pictures, but whatÔÇÖs happening online on social media deserves far more serious scrutiny than itÔÇÖs getting. If the art world doesnÔÇÖt admit more of this sort of deceptively casual-seeming work, the outside world will reject more so-called art photography than it already does. ThatÔÇÖs a divide that we donÔÇÖt need to reestablish and widen.

*This article appears in the August 11, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.