Who the hell is Thomas Ligotti? That’s the question many people were asking after a spate of articles last week speculated on plagiarism charges leveled against True Detective creator Nic Pizzolatto on an H.P. Lovecraft website. The media attention spiked sales of the book at the center of the controversy — Ligotti’s nonfiction philosophy tome The Conspiracy Against the Human Race — to the point that it began to outsell Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. HBO had to issue a statement refuting the claim, and social media raged (and may still be raging) with discussions of “Hey, just what is plagiarism?” Suddenly, too, Subterranean Press’s new Ligotti books — the rather dry metaphysical story collection The Spectral Link and a riveting collection of interviews with the author, Born to Fear — began to receive renewed scrutiny.

Which is all to good, because the “Who the hell is Thomas Ligotti?” question is the only part of this fuss that we should truly care about. Because Ligotti is nothing more or less than the king of weird fiction — his short stories are genius, and the relative lack of attention for that work constitutes a crime. The fiction he has created over the past 25 years has surpassed that of predecessors such as Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe in complexity and style, and it compares favorably to the prose of Franz Kafka. Ligotti has accomplished this feat and moved out of the shadow of his influences by grappling with the unknown in a way that eschews both religion and science as sources of the ultimate answers. He’s shown a devotion to finding the weirdness in even mundane rituals, and, yes, discovering a greater strangeness beyond that in fascinating approaches to the supernatural. During this span, only the brilliant Caitlin R. Kiernan, Joyce Carol Oates, and Brian Evenson have consistently done as much to expand the boundaries of weird fiction.

Yet, like some of his predecessors, Ligotti has been relegated to the status of “cult author,” his cause taken up by a devoted but small fan base. That cause hasn’t been helped by four factors: (1) Ligotti’s not dead yet (an unfortunate and embarrassing affliction, the living author); (2) he writes only short fiction; (3) he’s notoriously reclusive in our social-media age; and (4) despite being championed by editors at Virgin and Carroll & Graf, he hasn’t had a mainstream literary publisher give him the push needed to reach a wider audience. (Library of America, are you listening? Think of him as the Steven Millhauser of the weird and just jump right in there, headfirst.) Another complication is that in his approach Ligotti is allied less with American incarnations of weird fiction or horror than with iconoclasts like Angela Carter at her most surreal and Eastern Europeans like Kafka, Alfred Kubin, and the great Bruno Schulz. This makes his work more unique, but less commercial in purely genre terms.

Over time, Ligotti has moved from the more ornate to the more utilitarian in his prose style, and this almost certainly also corresponds to the move from stories that ritualize horror or riff off of Lovecraft to stories that show, for example, the ritualized horror of contemporary life. Perhaps his most brilliant innovation has been to turn the gaze of weird fiction toward the modern work environment, and to push past the blatant emptiness of the cubicle world to truths ever more horrific, subtle, and darkly hilarious. (Yes, once you acclimate to the weird elements, Ligotti can be a very funny writer; read “The Town Manager,” for example.)

[Editor’s note: The next paragraph contains spoilers for the HBO series True Detective, which, come on, you really should have watched by now.]

This emphasis in Ligotti’s fiction also reveals the irony in the charge of plagiarism, because the inexorable momentum of Ligotti’s fiction is so different from where True Detective wound up. The twist punch line, the monkey’s paw, amid all of this talk of plagiarism, is that True Detective in episodes seven and eight fell back on the kinds of tired horror tropes that Ligotti despises, using the trappings of his philosophy to set up something without the soul of Ligotti in it. To Ligotti, the revelation in True Detective that the murderer was a stereotypical, incestuous, stupid-sloppy killer hillbilly on a power mower would have been presented as a dark absurdity, not stark realism; it would have been further evidence of the conspiracy against the human race. Any sappy, prolonged redemption in a hospital would have been undercut in a million different ways or had some kind of vibrating sinister resonance beneath that made the reader uncomfortable. Nor, in Ligotti’s world, would we have ever seen the two detectives questioning Rust; nor would that frame have fallen away like the skin of a rotting piece of fruit to reveal that it was just a bit of stage business, a kind of banal misdirection meant to pin us riveted to our seats, and nothing more.

So, whatever you thought about True Detective or the True Detective plagiarism charges, you probably should be reading Ligotti — and here are five suggestions on where to start:

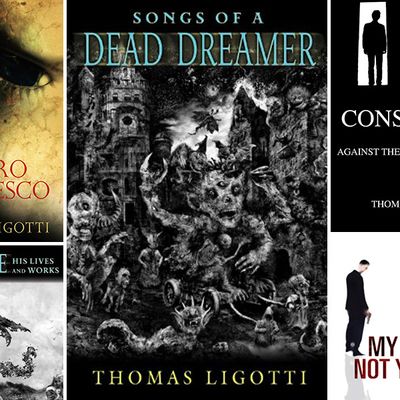

1. Songs of a Dead Dreamer

If you like beginnings, read this classic first collection, reissued by Subterranean Press with revised versions of the stories. First published in 1985 by Silver Scarob Press in a 300-copy edition with cover art by J.K. Potter and an introduction by Ramsey Campbell, Songs of a Dead Dreamer created great excitement, especially after a wider release in 1989. The collection should be viewed as just as significant to the evolution of the horror field during this period as the publication of work by Kathe Koja, Poppy Z. Brite, and Clive Barker. All the signs and symbols of Ligotti’s obsessions exist here fully formed, from the clinical yet rich style that allows for the right distance from transgressive events to a focus on masks, puppets, and rituals.

2. Teatro Grottesco

If, instead, you’d like a sampler, this compilation includes new material mixed in with some of Ligotti’s best mid- to later-era stories, like “The Town Manager,” “The Red Tower,” “The Clown Puppet,” and “In a Foreign Town, a Foreign Land.” There’s impressive range on display — from the absurd and at times hilarious to the unsettling, horrific, and otherworldly. “The Red Tower,” legendary in weird-fiction circles, can be read as a commentary on consumer society, a tour of Hell, or a quest into the deep modern subconscious. “The Clown Puppets” has an uncomfortable tactile feel that creates genuine unease while “In a Foreign Land …” showcases Ligotti’s ability for a lighter, almost delicate touch with its world-weary tone and odd parades glimpsed from afar.

3. My Work Is Not Yet Done

This groundbreaking collection includes three of Ligotti’s classic workplace stories. “I Have a Special Plan for This World” — one of the best titles ever — combines the claustrophobic horrors of corporate life with multiple murders. “The Nightmare Network” takes the form of memos from employees and managers along with other found texts, evoking disgust and unease with scenarios not far off from our reality. But the title novella, “My Work Is Not Yet Done,” is the juggernaut here, in more ways than just length. It’s a stunning tour de force that follows Frank Domino in a labyrinthine and Boschian journey after he tries to introduce a new product to his boss. From the wreckage of what occurs next, Frank plots revenge … except this is a Ligotti story, so what seems like a standard revenge fantasy morphs into something much deeper and more unique. Indeed, what makes the novella so compelling is that Ligotti reaches a point in the story arc where most writers would stop … and he keeps going. If “My Work Is Not Yet Done” were a movie, it’d be like Quentin Tarantino rewritten by David Lynch and then edited by Stanley Kubrick.

4. Grimscribe: His Lives and Works

This classic second collection solidified Ligotti’s reputation as a master of weird fiction. The shift from a Lovecraft influence to a unique voice continues here, especially in the gem “The Last Feast of the Harlequins.” An anthropologist visits the town of Mirocaw out of curiosity about a pageantry festival that includes clowns. In a perfect deadpan tone that allows the author a tightrope walk between the absurd and the horrific, the metaphysical and the visceral, the anthropologist comes to realize he has made an irrevocable mistake. Part of the pleasure here comes from the narrator informing the reader of information previously left out and inquiries into clown activities that are often dryly humorous.

5. The Conspiracy Against the Human Race

If you haven’t guessed yet from its position on this list, this now infamous philosophy book is not the place to start for new Ligotti readers. Start instead with his fiction, unless reading pages of convoluted despair philosophy is for you. I state this even though given Ligotti’s view of life, I don’t think he finds this subject matter depressing at all. Sobering, maybe — like another side to environmentalist Alan Weisman’s idea that we must imagine the world without humankind in it to begin the process of thinking of a new paradigm for the planet. But the truth is you need deeper thinkers than me to summarize this book, so here are pithy thumbnail descriptions of the ideas in The Conspiracy … from the exceptionally cerebral weird writer Michael Cisco and radical philosopher Steven Shapiro. Their words of hope and optimism may or may not remind you of True Detective.

Michael Cisco:

Alienation from nature is supernatural. This alienation acts by prompting human beings to deceive themselves about their own natures, especially with respect to freedom or happiness. These are impossible, he argues, but it is impossible to do without these ideas, and yet those of us who aren’t stupid can’t fail to realize all of the above. Confusion or bad conscience, or both, result … Horror appears where there can be no question of your intervention, and accompanies that recognition of impotence.Steven Shapiro:

The world has no meaning and no direction; it doesn’t satisfy our craving for stories with tied-up endings. Life is largely pain and tedium, and it comes to an end. Because we are conscious, we are horribly aware of all this, in ways that other animals are not.

Jeff VanderMeer’s latest novels are Annihilation and Authority, both published this year; Acceptance, the third and final book in the trilogy, will be published in September. He loves the first six episodes of True Detective.