Compared to good art,┬áÔÇ£great art is much harder to talk about,ÔÇØ┬áthe sculptor Charles Ray has said, speaking of the phantasmagoric work of Robert Gober, the subject of a 40-year retrospective survey at MoMA, called ÔÇ£The Heart Is Not a Metaphor.ÔÇØ ┬áÔÇ£If you were to ask me what┬áhis┬áartwork talks about I would not be able to tell you. But this doesnÔÇÖt mean it is not speaking ÔǪ What I do understand ÔǪ is that I want to see it again. It asks me to be near. To come closer and look longer or to come back tomorrow and look again. The work whispers ÔÇÿBe with me.ÔÇÖÔÇØ

The melancholy narratives of GoberÔÇÖs work have gripped and bewildered me for 30 years. Imagine Proust just presenting a sculpture of a half-eaten madeleine or drawings of┬áonly┬áthe three windows through which he watched illicit homosexual encounters.┬áThe novelist and critic┬áJim Lewis,┬áa┬álongtime close reader of GoberÔÇÖs work, is┬ánow writing a catalogue essay about him. In it, he┬áadmits, ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt understand Robert GoberÔÇÖs work.ÔÇØ He notes that most of this artistÔÇÖs commentators have recorded the same reaction, as well.┬áIÔÇÖm one of them. And thatÔÇÖs how I know how good the work is.

The first pieces we encounter inside GoberÔÇÖs stunning new MoMA survey will likely whisk viewers to this never-understand land, as well. ThereÔÇÖs a recessed closet with no door, a tiny intaglio print of an anonymous cat-sitter ad, and on the floor jutting from the wall ÔÇö as if crushed by DorothyÔÇÖs house crashing down into some eerie Oz ÔÇö a manÔÇÖs severed leg with pants cuff, hairy shin, and old shoe.

The whole show conjures a house possessed, stripped-down, roughed-up  Gobers inner home, ours, Americas. The second gallery zeroes in on a mad family of contorted sculptures of sinks. All evoke inanimate beings, anomalous anatomies, secret selves, hybrid bodies in pain, absence, emotional masks donned and removed. Made in 1984, these are the works that put Gober on the map  albeit off to one side. Famous but never as white-hot as Jeff Koons, Gober has always been viewed by the art world as some sort of good object, while Koons is seen as the bad object. This even though the two are pretty similar: about the same age, from working-class northeastern families, obsessed with sex, religion, history, freakish levels of craft, hygiene, and cleanliness (Gober with sinks, Koons with vacuum cleaners). Gobers sinks, fashioned from plaster, wood, wire lath, and coated in layers of bland semi-gloss enamel, slung low, are exoskeleton ghost sculptures, dysfunctional with no running plumbing. All holes and bowls, some look like mouths and feel more like urinals or creatures with needs  clunky, funny, wanting, bizarre. Gober has said, What do you do when you stand in front of sink? You clean yourself  (these sinks are) about the inability to (do that).

As you proceed deeper into this apparitional house, be forewarned. The repeated paleness of his palette, the hermeticism, almost empty rooms, and surrealism can make GoberÔÇÖs art turn wan, monotonous, joyless. In the next gallery two crooked playpens might mangle any kidÔÇÖs internal compass but the work is optically inert, emotionally obvious. Gober does ambiguity better. Way better. Which brings us to something of a skeleton key to GoberÔÇÖs work. A plain piece of plywood, made in 1987, leans against a wall. ThatÔÇÖs it. Look closely at the surfaces, edges, and materials. Crafted carefully from laminated fir and particle board, this is a work cloaked, camouflaged, passing as a piece of plywood passing as sculpture passing as art, blending in, acting one way while being another. It is a sculpture in drag.

A work from 1979ÔÇô1980, made when Gober was 25, a large dollhouse, is a near-perfect hand-rendered re-creation of a typical working-class American home. It is the kind of house you might pass on a shortcut on your way to school and think about how comparatively normal life inside it must be. In this exhibition, the work is shown with its sides closed, and therefore hidden, but in other shows theyÔÇÖve been thrown open, exposing whatÔÇÖs within to all. Inside, the house looks abandoned, and the walls are covered with painted scenes of roads, landscapes, shapes of the states. Alarm bells sound. These are images of longing, loneliness, dreaming of other places, getting out, getting away. That empty closet, severed leg, and disembodied sinks all transform into WhitmanÔÇÖs ÔÇ£phantoms curiously floating.ÔÇØ This is someoneÔÇÖs prolapsing life.

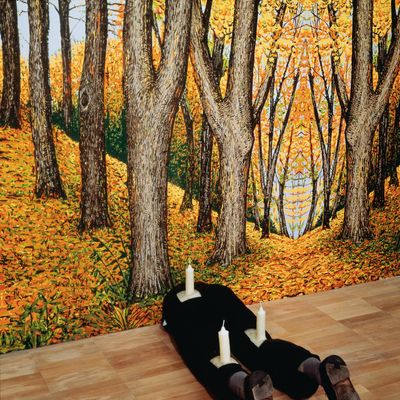

Nearby, another empty doorway ÔÇö and a work one of GoberÔÇÖs best critics ÔÇö curator Richard Flood referred to as ÔÇ£a curious bag of groceries.ÔÇØ A hermaphroditic torso with one male and one female breast. Human hair has been tweezed in. ItÔÇÖs as maniacally made as a Jeff Koons sculpture. Lumped on the floor and leaning against the wall like a sack of gravel, this is a body in conflict, psychic boundaries bulging, contested, cursed, alive with possibilities. By this point in the show, youÔÇÖve seen all sorts of hyper-realistic attenuated body parts jutting from walls, in corners, on the floor: A pair of manÔÇÖs legs with drains, anotherÔÇÖs sprouts candles, anotherÔÇÖs has sheet music embedded on his naked posterior. A large cement crucifix spouts a stream of water from ChristÔÇÖs nipples into a jackhammered hole in the museum floor. Tears, nourishment, violence, and sex mingle in this image of sacrifice and violent death. There is an empty wedding dress in a room wallpapered with repeating images of a sleeping white man and a hanged black man. ┬áIt sends chills. As does as a truncated naked female torso giving birth to a grown manÔÇÖs leg with shoe and pants, foot-first. When this untitled 1993 work was first shown I remember many being outraged at perceived misogyny, hatred. GoberÔÇÖs own mother said ÔÇ£Bobby, why would you want to make something like this?ÔÇØ Maybe it just says weÔÇÖre born this way. Either way many of these works still make the hair on the back of my neck stand up. As always with Gober, the important thing is not what the work says, or what itÔÇÖs about, but what it does to you ÔÇö what it brings up in you.

But where does it come from, this strange grotesque netherworld that is both horrifying and unshakably personal, intimate, familiar? Gobers art comes from many places and cant be reduced to identity politics, sex, religion, race, or psychology. Yet it helps to look at a context that helped forge this art. In 1981, the New York Times published a one column article titled Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals. Outbreak Occurs Among Men in New York and California. AIDS had come into the land. Rather than the U.S. mobilizing and the sick being succored by family, religion, and government, gay men were shunned, left to fend for themselves and die in public. By the time President Ronald Reagan finally said the word AIDs in over 21,000 American citizens had succumbed to the disease. Its hard to conjure what New York looked like then, what a ride on the subway was like. Emaciated, marked, scared men everywhere. People afraid, contemptuous of one another. Hate crimes were being directed against gay men and women; sodomy was declared a punishable offense. Gobers and our home had turned into a house of death. Gober said, I was a gay man living in the epicenter of 20th century Americas worst health epidemic. He later wrote that it is primarily gay men  who have organized themselves to care for their own when their families and their government recoiled in bewilderment and fear should gay men succeed in moving through the discrimination  their achievement will be remarkable. As surreal and beyond ones grasp as his art might seem, this is what the world was actually like then.

One of the last pieces in the show offers such sweet sustenance and hope. A simple potato print of the words of Rodgers & HammersteinÔÇÖs 1959 Climb Every Mountain, I found myself humming this song as I absorbed all the sorrow and lost souls evoked here. ItÔÇÖs pure schmaltz, maybe. But thatÔÇÖs a part of what weÔÇÖre made of ÔÇö gushing inexplicable feelings. And even when these feelings come from show tunes they can add up to sublimities. GoberÔÇÖs work exhorts, annoys, lulls, lets boredom slip in. Yet it almost always radiates a disquieting radical strangeness and in its weird way heals. He is one of the best American artists of the last 30 years. This impressive exhibition more than does him justice.