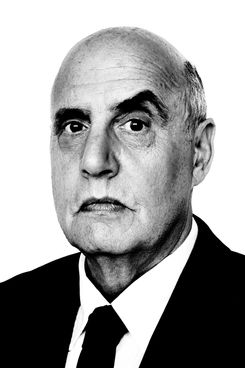

It is mid-August, and Jeffrey Tambor is sitting at the kitchen table, wearing a V-neck undershirt, baggy cargo shorts, and flip-flops that reveal toenails painted a tasteful brownish red.

“It’s my secret way of still touching her,” he says, gazing at them. “I’m afraid to put her down. I want her near.”

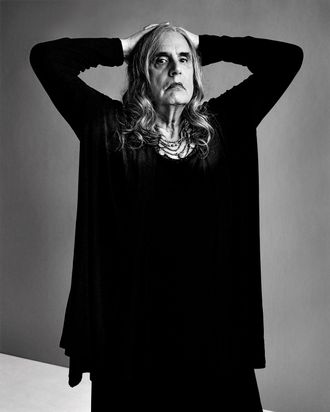

Filming ended two weeks ago on the inaugural ten-episode season of Transparent—Amazon Studios’ bid for a critical breakout—but Tambor still can’t let go of his character, Maura Pfefferman, a retired political-science professor making a late-in-life gender transition to female.

It’s no wonder Tambor feels so connected to his character: Just as Maura is beginning her new, true life, Tambor is also settling into his second act—or possibly his third or fourth.

“Mommy said I need to eat, and I want fried rice and turkey cold cuts,” says his 9-year-old son, Gabriel (born the same week as his grandson). Tambor married his third wife, Kasia Ostlun, in 2001, and the couple also have a 7-year-old daughter and 5-year-old twin sons.

“They’re my best teachers and inspiration,” he says of his children. “They keep me alive spiritually and physically. I don’t feel 70. I feel 50. There are times between five and seven when this house is like a bowling alley, but it’s reinspired me. My acting has gotten better because of these kids. I feel the same spirit I did when I was doing Off Broadway.”

Tambor heats up his son’s lunch in the microwave, then walks outside, unfurls the patio umbrella, and sits in a paisley lawn chair. The Tambors moved to the upstate village of Cross River, New York, from Los Angeles last year. “Movie stars are usually assholes and their wives are worse,” says Ostlun, a former actress, explaining the move.

“Smell that!” Tambor says, holding his arms out. “That’s why we’re here. Look at that tree. Seasons make you feel present.”

Tambor grew up in San Francisco in what he describes as “a traditional Jewish upper-middle-class family.” His father was a pro boxer turned floor contractor and his mother was a housewife. They lived across the street from San Francisco State University, where, as a kid, Tambor would sneak into the auditorium to watch the acting class rehearse.

“It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen,” he says, leaning back in his chair. “I realized whatever that was, art or whatever, was more interesting and better than life. Plus they welcomed me, this 8-year-old kid who had this lisp and was overweight.”

One day, while watching a production of Arthur Laurents’s Home of the Brave, he was invited to help strike the set. “There was a huge boulder, and they said, ‘Take this off the stage,’ and I said, ‘I can’t,’ and they said, ‘You can.’ It just rose above my head, and I went, Whatever this is, I have to do this, this magic. There are, what, half a dozen moments like that in life when you are so connected? It was a powerful moment, and I remember crying. I was overcome by it.”

Tambor would attend the same school to study acting. “I went bald when I was 18,” he says. “My father cried. He cried about many things. But it allowed me to play older men in summer stock.” After the actor playing Octavius Caesar mocked him during rehearsals for Antony and Cleopatra, Tambor treated his lisp with speech therapy. Off Broadway led to supporting roles in film and TV, his most steady gigs being a judge on the ’80s cop drama Hill Street Blues, followed, in the ’90s, by the hapless-buffoon co-host on The Larry Sanders Show.

At the time he was drinking heavily. “I was so out of control,” he says. “I was smoking and drinking and doing the whole thing.” Then in 2001, soon after playing the art critic Clement Greenberg in Pollock, he quit drinking. “If you see Pollock, I weighed almost 270 pounds,” he says. “A review said ‘the fleshy Jeffrey Tambor.’ That didn’t prompt my sobriety, but that’s when I knew trouble was a-brewing.” Around the same time, he married Ostlun, whom he’d met a few years earlier on the set of Meet Joe Black. Then, in 2003, he landed the role that made him, if not famous, then at least a cult favorite: George Bluth Sr., the squirrelly paterfamilias on Arrested Development.

When the show was canceled in 2006, Tambor fell back on character acting. “I didn’t think, Oh, gosh, I’ll never work again and be selling oranges,” he says, but his career did seem to be regressing, especially after he left Los Angeles. He made the rounds of locally filmed shows like Law & Order: SVU and The Good Wife. Then Transparent came along. “I was stunned. It was so brilliant and right,” he says.

A family drama peppered with dark comedy, Transparent has as much in common with Norman Lear’s “issues” sitcoms of the ’70s, like Maude and All in the Family, as it does with marquee cable series. And it’s not just the of-the-moment story line of its lead character. Her three children, played by Jay Duplass, Amy Landecker, and Gaby Hoffmann—who partakes in perhaps television’s most awkward ecstasy-fueled three-way—are all self-obsessed Silver Lakers going through their own (albeit less physical) transitions: In the first few episodes Transparent tackles abortion and an extramarital lesbian affair.

“That’s part of the design of the show,” says Tambor. “There is laughter and feelings and tears. The gyroscope moves quite a bit, as does life.” And like that other breakout web-only show, Orange Is the New Black, it puts transgenderism in front of viewers without ever making it the butt of the joke. “Ultimately, this is going to put light and clarity on a subject that needs it,” says Tambor. “The conversation is going to move way forward.”

Jill Soloway, the show’s creator and a former producer for Six Feet Under, based the series in part on the experiences of her father, who began transitioning three years ago. The show became a way for her to process her own experiences with her dad. “It’s created out of my desire to make the world safer for my dad to walk out of their apartment building,” she says. (“Them” is her dad’s preferred pronoun.)

In interviews, she has been careful to protect her father’s privacy. “My father is super-excited for the show, but I’m trying to let them take their time with how much they want to expose about their own life.”

She’s taken pains to portray transgenderism with compassion, down to hiring members of the crew, who were selected on the basis of what she calls “trans-firmative action.” Trans people worked in all departments, from camera to catering to transportation, and many of the supporting actors are transgendered.

She also brought on Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst to serve as trans advisers to the show and provide sensitivity training for the entire crew and cast. “Early on in production meetings,” says Drucker, “Rhys and I gave out a cheat sheet: ‘What does misgendering mean?’ ‘What do you do if you don’t know which pronoun to use?’ One thing that happens when it comes to interfacing with trans people is people are worried they are going to say something wrong.”

Still, all of that sensitivity training might not be enough to dampen the criticism of having a non-transgendered actor in the lead role, something the show’s team is, well, sensitive to. When Jared Leto won an Oscar earlier this year for his turn as transgendered prostitute Rayon in Dallas Buyers Club, one trans writer wrote that the actor was perpetuating “the stereotype that we are men in drag.”

Drucker argues that Tambor’s performance transcends the criticism. “Jeffrey has approached this character from the inside as a human,” says Drucker. “It’s understandable that many people have passionate opinions about a cisgender actor playing a trans person, but I hope they reserve judgment until after they see the show.”

Tambor as Maura certainly has none of Leto’s sultry charm. For one, she has a penchant for breathy caftans. “I told the stylist, ‘Think of your perfect Jewish therapist on vacation in Martha’s Vineyard,’ ” Soloway says.

“She’s not hip, and I love that about her,” says Tambor. “She has glasses and doesn’t wear high heels and isn’t trying to be something she isn’t.”

Tambor was Soloway’s first pick for the lead. “Whenever I’ve seen Jeffrey on TV, he reminded me of my dad,” she says. “Maura is real, and she needed Jeffrey. It’s like she’s a spirit possessing Jeffrey. We have no choice but to bow down to her desires.”

Tambor’s preparation for Maura was immersive. Drucker and Ernst helped him get into drag and took him to a trans club. “I was so nervous about getting out of the elevator and walking through the lobby to the car,” Tambor says. “I thought, Please remember this. This is how it feels every time.” Tambor also went shopping and to lunch dressed as Maura. Once, while waiting for a plane at La Guardia, he got so caught up studying his lines that he went into the women’s bathroom. “I was thinking about Maura so much,” he says, “that MEN and WOMEN signs made no sense to me, and some woman went, ‘Sir, sir!’

“I would wear the undergarments around the house,” he says. “As cliché as it would seem, it did help. But at a certain point I had to go within and find the truth in me and make it personal. I was nervous about it. I wanted to do well for me and for Maura. It is bigger than me. I have a responsibility. It’s incumbent upon me to do Maura the best I can.”

Tambor looks out at the tree line and continues: “It’s about freedom, isn’t it, when you get down to it? Imagine the courage it took her to say, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ ”

*This article appears in the September 22, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.