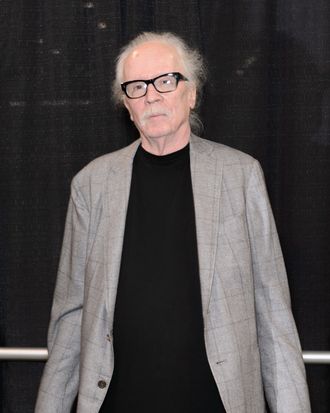

Horror filmmaker John Carpenter’s body of work is atypical in that his films often seem to have been made by an uncompromisingly intuitive commercial artist. Never content just to take a check, Carpenter abandoned the Halloween franchise after co-writing and producing the series’ first two unsuccessful sequels and took on bold projects, such as Big Trouble in Little China and Prince of Darkness that suggested he knew how to make movies without giving in to creative pressure to make palatable pablum. Vulture talked to Carpenter about how he resolved key conflicts on projects that defined his career, particularly The Thing, his Halloween sequels, and others.

In The Films of John Carpenter, author John Kenneth Muir writes that an early cut of Halloween was deemed “not scary enough” and you spent two weeks reworking it, and adding the score.

No, that’s incorrect.

That seemed like an odd coincidence since you also said that about an early cut of Halloween II. Was that just Halloween II then?

That’s right, it was just Halloween II. Halloween was cut together and was just right. All it needed was music.

How did you collaborate with [credited co-writer] Debra Hill on the Halloween II script?

On that particular script, I wrote most of that by myself. That was a painful script because I didn’t feel like I had any story. And the only thing I could think to do was to start immediately after Halloween ended, and just carry on. And it was a script I wrote with a six-pack of beer every night, trying to get some inspiration.

Do you remember what beer you were drinking?

I would think Budweiser because it would give me a buzz, but wouldn’t get me drunk.

How did you break the news to [director] Rick Rosenthal that the rough cut of Halloween II he submitted just wasn’t scary?

He showed me his cut, and I said, “There’s one thing that this really has to be, and that’s scary. And it isn’t quite there yet. So I want you to take” … I forget how many days I gave him. But: “Take a few days, and work on it.” And nothing really changed. So I said, “Well, I’m going to have to fix this.” We did a little recutting, and then we did some reshooting.

Weren’t most of the scenes that were added ones where Michael [Myers] attacks people? Is that an exaggeration?

That’s not quite it. There were, however, two scenes added where he attacks other characters.

You and Hill have talked about how slasher films were passe, and that the best way to proceed with Halloween III and succeeding sequels would be to make them about the holiday Halloween, not Michael Myers.

I would never put it in those words. I would never use the word slasher. That’s a word that was made up later. I thought, I don’t think there’s any story left here. So let’s do something else, come up with a new story. That’s how it started. I was talking with Joe Dante about it, and he said “You know [British science-fiction writer] Nigel Kneale is in town, and he may have a good story. Let’s go talk to him.” So I ran out to talk to him; it was Joe, Debra, and myself. And he was working on Creature From the Black Lagoon out at Universal. He came up with a story that I thought was real interesting.

Dante was at one point attached to direct that Creature From the Black Lagoon remake, as were you. Was Dante working on that film at the time you approached Kneale?

I don’t think so. I wanted Joe to direct Halloween III, but he didn’t end up doing it.

Was he too busy?

I don’t remember now.

Other than the holiday theme, were there any other plans for how to use Halloween III as a model for succeeding Halloween sequels?

It wasn’t that. We thought we’d take it a project at a time. Halloween III was just a good story. It was a different story: It didn’t have Michael Myers in it. Which is the reason it wasn’t a hit.

What kind of discussions did you have with Nigel Kneale about his script, before and after changes were made to it?

We just let him write it. His first draft wasn’t very sharp, and it had a lot of British stuff that no one understood. The main character works in a British hospital where no one gets healed. I’m not quite sure what that means: Is it a poor area? Is it a poor hospital? Sounds odd. We had a director at that point, Tommy Lee Wallace. And he began to work with Nigel on the rewrites. But Nigel Kneale didn’t want to change anything of his precious writing. And it wasn’t up to what we needed it to be. So we worked on it, Tommy Lee and I. Nigel Kneale is a brilliant writer, but by the time I met him, he was pretty irascible, and mean. He was a mean character. He started making fun of Jack Arnold, the director of the original Creature From the Black Lagoon. At that point, Jack Arnold had lost a leg. And Nigel made fun of him for that. Terrible. [Nigel] thought he was above us, us horror filmmakers.

That’s striking, since your Prince of Darkness is an homage to Kneale’s work.

He didn’t care about any of that. If he didn’t do it? Bullshit.

But your estimation of his work didn’t change over time.

No, I really loved his original stuff. I just think he’s groundbreaking … but unpleasant to work with! [Laughs.]

When they made Halloween IV, did you have any alternative plans for sequels?

No, I was not involved after [Halloween III].

You’ve previously said that Dark Star’s failure to attract more and bigger projects caused “the first depression of my life” but was also invaluable in that it tempered your expectations.

That’s right. You’re right.

Can you remember the moment when you realized Dark Star didn’t make the impact you wanted it to?

[Laughs.] I don’t know! I guess when I realized it didn’t make me money. I don’t know.

Similarly, you saw the rough cut of The Fog, and knew that it didn’t work. How did you steel yourself to tell the film’s executives that you needed more time and money? What was your feeling and who did you talk to about this?

The head of the studio. I just walked in, and said “We need to work on this some more.” And they said “Okay!”

Wow, really, as easy as that?

[Laughs.] Yeah.

So you knew you would get that response? That’s a tough call to make given that you’re an artist, and you have to navigate the studio system to get your films made. So you have to be diplomatic, but you also work on instinct, knowing what works, and what doesn’t. So that’s a delicate balance, especially when there are expectations …

That’s well said. [Laughs.] That’s what I think, too! You’re trying to deliver expectations of people that give you the money, so you have to put that in the equation. You can’t just do what you want. You try to give them what they want. And what they want in the end is a hit. So if you can deliver a movie that makes money, that’s good. So the times I’ve said I don’t believe it’s good enough … I just didn’t believe it was good enough. We had to make it better so the studio, the producers, everybody would be happy.

You submitted a shorter, less violent print of Assault on Precinct 13 to the MPAA that the one that was theatrically release.

That’s not quite accurate. We were going to get an [X-rating] because of the little girl scene …

With the ice-cream cone.

Correct. So the distributor said “Just cut the shot out for the ‘R,’ and we’ll release it as it is.

Did anyone catch on?

Nobody said anything to me.

Fast-forwarding for a minute: [Texas Chainsaw Massacre co-creators] Tobe Hooper and Kim Henkel worked on the script for The Thing at one point.

Yes. They wrote a whole draft before I came along. All sorts of drafts were written before I came along. One was underwater … they were just trying to make it work.

Did you meet with them, or any of the other screenwriters?

No.

With regard to that film’s score: As a point of reference, you referred to Max Steiner’s scores as “music that disappears.” What other points of reference did you have, or did you have a specific Steiner score in mind?

Steiner’s music did not disappear. I was comparing Mickey Mouse–ing to the kind of music that I do. Mickey Mouse–ing is what Max Steiner did in King Kong. The footsteps of King Kong are scored: bom-bom-bom. Mickey Mouse–ing is over-scoring. It’s what happens today. Everything is over-scored. Minimalist music, a lot of it from my time — ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. Tangerine Dream did some. The Exorcist’s score is another. They weren’t Mickey Mouse scores. By Mickey Mouse, I don’t mean dumb, or cartoonish, but everything was musically it: footsteps, everything. That’s what Steiner was famous for.

Creature effects designer Rob Bottin says that he suggested playing the film’s five violent transformations up as “fantasy,” partly to nip censors’ objections in the bud, especially in the way the thing’s internal organs look, and the color palette. He was working on creature effects for the film right down to its release, though, if I understand correctly. What kind of conversations did you have with him on the film?

Oh, man, I can’t even begin to go into it with you, there were just so many. But we did decide at one point to calm down the blood and viscera’s color. That is true. But we decided that after we shot a bunch of it. But that wasn’t our grand scheme from the beginning.

After making The Thing, you read a demographical study that said the audience for horror movies shrank by 70 percent over a six-month period.

Yes. It was shocking! [Laughs.]

Can you remember where you saw this?

It was sitting in my office at Universal. Universal had sent it over.

Was it their way of saying “Lower your expectations”?

Yeah: “Brace yourself.”

This must have been around the time that you did a rough cut …

No, it was after we were finishing it.

Wow, that’s demoralizing! This was a really daring movie for a studio film. You seemed to have a clear vision for this film, but how much of a vacuum are you in, working with actors and guys like Bottin on achieving a certain effect? Did you routinely look at rushes, and say “This is exactly what I want”?

[Laughs.] Well, it all starts with the planning. To plan the movie, you make certain decisions, and you live by them. Casting is the biggest thing: You cast the actors, and then stay out of their way. Give them what they want to do their best job. The same was true for Rob Bottin: In the project we originally came up with, the creature was just one thing. And Rob’s idea was that it could look like anything, and it keeps changing. So I went with that. My job was giving him everything he needed to do his best job. Sometimes we’d discuss the design of it in a particular scene and walk through it together. It’s an ongoing process, but once you make that first decision, then you’re into it.

In 2000, you taught a class on sexuality and brutality on film.

Sex and Violence in Cinema, that’s correct.

At University at Santa Barbara. You showed stuff like Straw Dogs and In the Realm of the Senses, but was Blood Feast on your syllabus?

No, it was more of a sophisticated … I could have, but it was more of a historical class. What I wanted to do with the class was get conversations going. I wanted to get kids to think about what they’re watching. So the movies that upset them the most were Straw Dogs and In the Realm of the Senses. Those movies really stirred up emotions.

Terry Gilliam recently said that when you’re between films, it feels like you’re in a strange limbo: You’ve got one project out of your system and are now waiting for the next one to latch onto. How did you reviews and the general reception of The Thing hit you? One notoriously unkind reviewer said that you were “a pornographer of violence.”

Like any human being! [Laughs.] There’s no secret to it: You just have to develop a thick skin, and you just keep going. You just don’t let that stuff get you.

Even after The Thing’s failure, you didn’t jump at any project offered to you … you were offered Top Gun, no?

I don’t know that I was offered it, but I did read it. I wouldn’t have done it even if they did offer it to me. It was ridiculous!