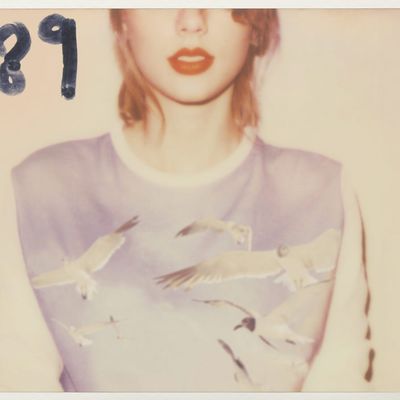

If the past decade in pop has often felt like a dark, twisted, apocalyptic rager, Taylor Swift has been its designated driver. Poised, dependable, and preternaturally self-possessed, Swift has fashioned herself the sober-eyed observer in the corner, meticulously and sort of mischievously cataloguing the sordid details that everyone else will be too shitfaced to remember in the morning. (“22,” Swift’s requisite but irresistible take on the Millennial Party Anthem, proved that her idea of a wild time was not swinging from a chandelier or dancing with molly but eating breakfast … at midnight.) Of course, Taylor Swift has been invited to this party for years now — arguably since her 2008 album Fearless, which yielded country-to-pop crossover hits like “Love Story” and “You Belong With Me” — but she is choosing with great fanfare to call her fifth full-length, 1989, her “very first documented, official pop album.”

Not so fast, though: She would like us to know that 1989 is not your ordinary, run-of-the-mill, “evil pop” album. “Evil pop is when you’re singing something in your head … and you don’t know why because it’s brainless,”she said in a recent interview with her collaborator Jack Antonoff. “We wanted to keep this pop clean and good and right, and if it’s stuck in your head I want you to know what the song is about as well.” This quote is telling: At every stretch, 1989 is an album that believes in its own “goodness,” but also one that sees goodness as an adversarial stance. On one of its best songs, the sassy, bleacher-stomping “Blank Space,” Swift calls herself “a nightmare dressed like a daydream” and boasts, “I can make the bad boys good for a weekend” so confidently that it comes off as a threat.

For anyone even remotely skeptical of Swift’s new, self-proclaimed pop direction, the stretch leading up to 1989 has been an emotional roller coaster. First we got “Shake It Off,” her attempt to write the kind of Pharrell-esque, world-conquering pop song designed to make all the other songs played during the Ellen commercial break cower in shame. When I am not listening to “Shake It Off,” I have quibbles with the Idea of It; when I am, I forget them. I have sung it into a hairbrush in the last 48 hours. It is a very good pop song. Once “Shake It Off” had effectively achieved its planned domination, Swift revealed something even more promising: the cavernous, Antonoff-produced “Out of the Woods,” which seemed to herald an exciting, unexpected, and mature new direction in Swift’s sound. Only a week later, though, these hopes were dashed against the rocks by the listless electro-pop track “Welcome to New York,” which sounded less like the work of a multi-multi-multi-award-winning songwriter and more like a song that a Franklin Lakes investment banker purchased from ARK Music Factory for his daughter’s Super Sweet 16. We all wondered which of these very different songs would be most representative of 1989, and when I saw that “Welcome to New York” was the opening track, I will admit I feared the worst. But the good news is that the song isn’t quite as much of a disaster in context. It’s still an unforgivably dull mission statement, but it’s really only here to set the scene: Welcome to New Taylor. A clean and bright and shiny place where the subway never smells like piss because you never have to take it.

But once “Welcome to New York” is endured, or perhaps skipped, 1989 really hits its stride across a stretch of three songs on which Swift seems to be making pop music bend to her will, rather than the other way around. “Blank Space” is a brighter, chirpier take on Lorde’s brand of minimalist electro-pop. Then comes the audaciously named, Patrick Nagel–slick “Style,” which is such a good Don Henley song that I hope whoever directs the music video has the sense to shoot it in black-and-white and film Swift in close-up on the back of a truck. All of this momentum ramps up to “Out of the Woods,” which ends up being the album’s most triumphant moment — it’s not only the song that unites ‘80s and contemporary influences most seamlessly (very Hunger Games Without Frontiers), but also the one that brings you most immersively into Swift’s world. All Taylor Swift songs are written from the perspective of the girl who Feels It more than everybody else; the goal of every Taylor Swift is for you to fleetingly feel it as much as she does. “Out of the Woods” has such a captivating, driving momentum that it’s hard not to get swept up in its melodrama. For four minutes, at least, we believe her when she says the trees are really monsters.

1989 can’t quite sustain this run, though. The back half too often finds her chasing the sounds of her peers rather than articulating what sets her apart from them. The vaporous, fog-machine ballad “Wildest Dreams” sounds like the work of a Lana Del Rey lyric generator, and the forgettable “I Know Places” is a Lorde song in all but name and … quality. (Ryan Tedder, who co-wrote “Places” and “Welcome to New York,” bats 0 for 2 on 1989.) It’s kind of ironic that “Bad Blood” is such an obvious Katy Perry dis, because the faceless mall-pop of songs like “All You Had to Do Was Stay” and “How You Get the Girl” proves that Swift is no better with early-’90s pastiche than Perry was on Prism’s duds “This Is How We Do” and “Walking on Air.” It seems likely that Swift’s comments about “brainless, evil pop” are at least partially directed towards Perry, but toward the end of 1989, the line she’s painstakingly drawn between herself and other artists grows less and less clear.

Yesterday, I put 1989 to any Taylor Swift album’s ultimate test: I played it in a car while driving around with some of my girlfriends. When it was over, one of them said, “I kept forgetting we were listening to a Taylor Swift album and not just listening to the radio.” In some sense, that’s a compliment — almost any one of these songs could (and probably will) be hits. But in the process of streamlining her sound, Swift has sanded off a lot of the edges that once made her perspective so unique. The disappointing thing is that she didn’t really have to. More and more these days, going pop is seen as a declaration of independence rather than a manifesto of self-imposed formulaic limitations. (I sometimes think of a quote from an early interview with Icona Pop, who declared, “You can do whatever you want and call it pop!”) Swift’s definition of the genre is a little old-fashioned, and laying out such a self-conscious plan to make a “documented, official pop album” seems to have boxed her in. As much as she’d like us to see 1989 as a reinvention, it actually strikes me as her most conservative record, sticking to the speed limit at almost every turn.

*This article appears in the November 3, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.