The title Whiplash is dead-on. That’s what it is; that’s what it gives you. Miles Teller plays a young drummer, Andrew Neyman, who announces to anyone who’ll listen that he wants to be “one of the greats.” Long into the night, he thumps on his drums, blisters opening, blood smudging his sticks. The movie charts his education/torture at the hands of an instructor named Terence Fletcher (J. K. Simmons), who conducts the elite jazz band at the Manhattan conservatory where Andrew is a new student. Film has a long (dis)honor roll of sadistic teachers and drill sergeants, but few have looked like they were getting as much of an erotic thrill out of brutalizing (or outright destroying) their charges. In the course of a gut-twisting, appalling two hours, writer-director Damien Chazelle has you wondering two things at once. Will Andrew finally succeed in wowing this most exacting of judges? And, more important: What can be gained by doing so when the man is manifestly psychotic?

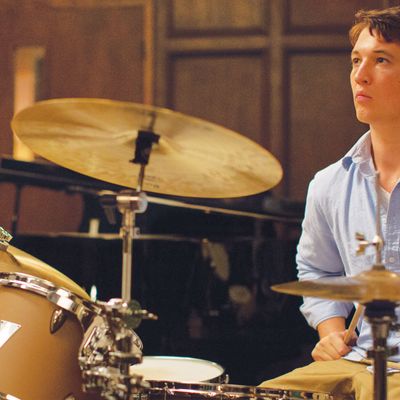

As a go-for-it music movie, Whiplash is just about peerless. The fear is contagious, but so is the jazz vibe: When Andrew snatches up his sticks and the band launches into a standard—say, Hank Levy’s “Whiplash”—it’s hard not to smile, judder, and sway. Teller was a drummer as a kid and does all the character’s playing, so Chazelle doesn’t have to hide his hands. The camera sweeps toward Andrew from the side, arcs around him, pulls back, zooms in. The style is keyed to the tempo—it’s as if Chazelle were extending the music into space. Except for the occasional grimace, Teller’s face is rapt: He’s playing, he’s not acting playing. And when he isn’t playing there’s no wasted motion. Andrew is keeping his head down, conserving his energy. Early on, he courts a college girl (Melissa Benoist) who works at the refreshment stand of a revival cinema, but he drops her—coldly—when he thinks she might become a distraction. The conservatory is now his entire universe.

As Chazelle presents it, that school is not a social place—no kibitzing, no empathetic glances, only glumness and the terror of being replaced in a snap by someone else. Simmons’s Fletcher materializes in the doorway of his class like a vampire, the skin on his bald dome taut. The ridges in his sallow face are deep and hard, like the belly of a frog fresh out of formaldehyde. There’s no fat on him—he’s all teeth and dome and sinew. As an actor, Simmons is usually self-contained to the point of spookiness, but his Fletcher is so inscrutable he’s bloodcurdling. Suddenly, he’ll be warmly attentive, telling Andrew that the key is “to just relax, have fun,” asking about his family, making sympathetic noises as the young man explains that he grew up with his dad after his mom moved out. A moment later, Fletcher is taunting Andrew in front of the band and attacking his father’s masculinity. (Some audiences have been taken aback by Fletcher’s homophobic slurs, which are baroque.) He hurls chairs; makes students play until they bleed; screams, “If you deliberately sabotage my band, I’m going to fuck you like a fucking pig!”

His behavior is monstrous, but the question hangs: Does Andrew at this point need a “bad” father? Andrew’s real dad (Paul Reiser) is a soft, mild presence, a man who watches black-and-white movies and sprinkles Raisinets on his popcorn. He loves Andrew unconditionally—which is just what we want from a parent, right? The absence of such unconditional love fuels billions of hours of therapy and is the root of a thousand unreadable memoirs. But to go to the next level, does an artist need to fear being shamed? Fletcher likes to hold forth about the teenage Charlie Parker, who fled a Kansas City jam after drummer Jo Jones threw a cymbal at his head, vowing to be back—only better.

Whiplash will spark debate—some of it angry—over whether, in the end, Chazelle is vindicating Fletcher’s methods, suggesting that only a harsh taskmaster can push Andrew to the next level. I don’t think he’s that conclusive. But he’s certainly leaving the question open. When you read Jan Swafford’s exhaustive new Beethoven biography or listen to world-class musicians or Olympic athletes talk about their driving parents and lack of a “real” childhood, you see how pushing kids to the brink can in some cases pay off. It can also—more often—be inhuman, soul-killing, even criminal; it can screw people up for life. I know a woman whose gorgeous soprano was destroyed by an abusive teacher. And I know actors who went further than they ever thought possible under directors who played sick games with their heads. A good dramatist doesn’t need to reconcile these two sides, only bring them to life.

At the end of Chazelle’s audacious, low-budget debut feature, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2009), the protagonist, on the verge of losing his lover, plays a long, plaintive, increasingly desperate and discordant trumpet solo. He’s pushing against the limits of his talent, maybe the limits of his soul. Where art is concerned, Chazelle doesn’t believe in going after something within reach. He wants to push the limit—by any means necessary. His heroes are artists-existentialists: They create themselves anew every day, beating the drums and bleeding on them.

*This article appears in the October 6, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.