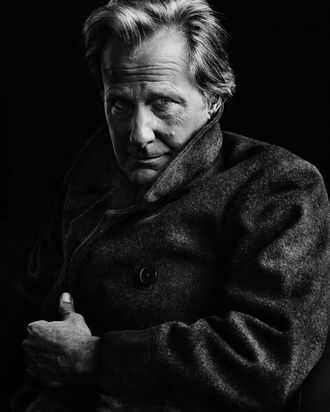

“Excuse me, Jeff Daniels? Can I take a picture with you?”

“No, but thanks, sir,” says the actor, shaking the fan’s hand and moving on, heading the wrong way up the bike lane of Central Park’s West Drive. “You’ve just got to keep walking.” In a Carhartt jacket and loose wool shirt, he looks inconspicuous enough, but his puppyish, elastic face, which his father once told him he’d “grow into,” is everywhere. Two weeks after our interview, HBO will launch the third and final season of The Newsroom, Aaron Sorkin’s well-rated, critically hated HBO soap opera–cum–civics class, in which Daniels plays Will McAvoy, a cable anchor who dares to practice Real Journalism. Five days after that will be the opening of Dumb and Dumber To, the very belated sequel to a movie that made a quarter of a billion dollars and turned this creature of the stage into a slapstick star. “I made a career on range, so there’s the range,” he says. “I couldn’t have planned it better.”

Though he admits he might have planned it earlier. “At 21, driving through the Holland Tunnel, your eyes wide open — if I’d have slipped into the passenger seat and said to myself, ‘By the way, um, it’s not really gonna happen for you until you’re 59, but just hang in there’? I’d have turned around. Gone back to my dad’s lumber company. Fifty-what? I didn’t think I’d be alive at 59.”

Daniels is an engrossing narrator on the topic of his own perpetual marginality — as he sees it, anyway — a point on which he vacillates between pride (“Welcome to my career path, where I make decisions”) and pain (“I got tired of being that guy that they used”). Both attitudes might look to an actual outsider like the narcissism of Hollywood’s small differences: Whether you’re the first or the fifth actor called in to read a part, it was still you starring in Terms of Endearment, The Purple Rose of Cairo, the epic Gettysburg, and Jonathan Demme’s money-losing but memorable Something Wild. In the unironic, matinee-idol ’80s, Daniels had made it, but not like other people had, which sometimes felt like not making it at all. So he took himself out of the race.

Even when Daniels made that first drive east in 1976 to join the Circle Repertory Company, part of him was still in Chelsea, Michigan, where he’d met his wife and where his father had once been the mayor. He made bargains with himself — “I can stay for five years,” and then, after five years of Off Broadway, “until I’m 30.” A couple of years before the second deadline, he landed a role as Debra Winger’s dopey but devious young husband in the 1983 weepfest Terms of Endearment. Daniels joked to his Circle Rep colleague Timothy Busfield that he was appearing in The Kid’s Big Break. The film won five Oscars from its 11 nominations — none for Daniels. “My friend said, ‘Even the guy who combed your hair got nominated,’ ” he says. It stung, “but, at 28, to have somebody slam the brakes on, it’s okay.”

As he tells it, he fell back on the advice of his theatrical mentors, Circle Rep founder Marshall Mason and the playwright Lanford Wilson. “I was told, ‘You’re not an actor, you’re an artist.’ I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew it didn’t mean going to L.A. and trying to be famous. It meant doing things that only good actors would try to do.” So he tried something radical, at least by the tooth-and-claw standards of Hollywood. In 1986, Daniels, his wife, Kathleen, and their 2-year-old boy moved back to Michigan — not as a movie-star lark but as a pivotal moment, a choice around which he believes the rest of his career has hinged. “I didn’t know how to bring a kid up in New York, and I sure as hell didn’t know how to do it in L.A. So let’s go back to where we know how” — they had two more children there — “and let me just be an actor for hire. You bring me in, a producer’s gonna love me, I’m gonna work with your A-lister. I’ll save you money. And then when I’m done, I’m gone.”

In Chelsea, Daniels founded a regional theater, the Purple Rose, for which he’s since written 15 plays in a variety of registers, on subjects ranging from bumpkin Michigan “Yoopers” (Escanaba in da Moonlight) to the gender politics of vasectomies (The Vast Difference). Several have been produced around the country and in New York, and Daniels adapted two into indie films. He also writes and performs countrified folk songs, some of them about Hollywood — on working with Clint Eastwood, on being mistaken for Jeff Bridges. By eschewing L.A., he says, he recused himself from the pressure to brand himself as a type, the traditional leading-man path for everyone from Clark Gable to Jim Carrey.

But by the time Dumb and Dumber was offered, disengagement had curdled into dissatisfaction. The day before flying out for his first fitting, he was on the phone with three agents, two of whom were convinced he was ruining his career. No, he told them, he was rescuing it. “I want to do comedy, I know I can. I want to change it up, because the career is starting to do this,” he says, tracing a lazy downward spiral with his finger.

“I would have taken anyone,” says Peter Farrelly, half of the Farrelly brothers, whose lowbrow-humor juggernaut was launched with Dumb and Dumber after dozens of actors turned it down. “The white guy from In Living Color wants to do it? Great!” With Ace Ventura: Pet Detective coming out, Jim Carrey had enough clout to insist that his buddy be a straight man. “Jim said, ‘A comedian will just try to top me,’ ” says Daniels. “He said, ‘I need someone who’s gonna force me to listen and react.’ ”

Someone had to be the dumber one, and “my job was to get my leash jerked this way and that,” says Daniels, “because we can’t both be pulling it.” Walking down Central Park West, Daniels pauses to show me the work that goes into turning himself into Harry. He gives his head the vigorous shake of a golden retriever fresh out of a lake. His face droops, tongue protrudes, hair spontaneously frizzes. Daniels will spend the rest of the afternoon smoothing it back into McAvoy mode.

Dumb and Dumber is designed to be stupid and forgettable, yet it’s so pervasively memorable that a sequel feels reasonable, even inevitable, two decades later. The Farrellys are credited with reinvigorating the gross-out-humor genre, exemplified by Daniels’s performance of the pleasure-pain frisson of diarrheal release. Farrelly pegs the movie’s success, though, to the humanizing bromance between Harry and Lloyd as they proceed through their cross-country road trip — and he says he has the numbers to prove it. All the Farrelly movies test well with more than 80 percent of viewers under 25 and men over 25, but the numbers usually sink to 30 percent among women old enough to rent a car. “On this movie, women scored 92 percent,” he says. “And it’s because they love these guys, because they give you real moments. That’s what keeps people coming back.”

According to Farrelly, Carrey was paid $7 million for the first movie. The studio, still hoping for another comic, offered Daniels around $75,000. “They figured he’d say ‘Fuck you,’ but he took it,” Farrelly says — accepting a 99 percent pay gap that presumably only widened on the back end. Daniels will say only, “Some got paid on that, some didn’t.” His deal for the sequel is much better, “and I’ve earned it.”

Today, he admits those nay-saying agents were both right and wrong about the impact that playing addle-brained Harry would have on his career. “ ‘What’s his Q rating, is he bankable?’ — all that stuff matters, and one movie did that for me.” On the other hand, he says, “You’re off the Oscar trail, that’s for sure. It was easily five years where I was no longer a serious actor.”

Daniels bought his New York apartment in the late ’90s, and “it’s worth more than I paid for it,” but it could use an update. One of the few fancy touches is a set of guitars hanging from a wall by the nonworking fireplace. During a break in our conversation, he pulls one down and strums it absently. I suggest he might play a song.

“Oh, if you want,” he says. Anything on topic? He offers a rambling bluegrass number titled “Now You Know You Can.” “It’s about that Northwestern speech,” Will McAvoy’s first-episode-opening, Network-style rant about America’s decline. “It was day three of the pilot, and we don’t have a series yet,” Daniels recalls, setting the scene. “Well, we all love Jeff, but do we have a star? Everything is riding on this — and, by the way, a career.”

Sorkin remembers offering him cue cards, whereupon Daniels shot him a look that “unambiguously said, ‘Or I can help you shove the cards up your ass?’ Then he literally recited all the statistics from the speech forward and backward.” After a powerful first take, the script supervisor walked over and told him, “Now you know you can.” Daniels plays half the song for me, half-remembering it but closing strongly on the chorus: “Spread the news in another man’s shoes because now you know you can.”

After his bitterly comic 2005 turn as a jerky Park Slope dad in The Squid and the Whale, Daniels campaigned aggressively for an Oscar and was snubbed again. But, he says, he made his peace. “I thought, Okay, I’m gonna be Gene Hackman,” aging into a steady stream of eccentric lead roles. “Well, that became difficult, because for the next three years you get asshole-father roles, just like in Squid and the Whale — but now you’re the asshole father to a 26-year-old star who’s making $10 million and can’t find his mark.”

Daniels did other indie films, but instead of feeling liberated, he felt exploited — underpaid on movies more amateurish than Dumb and Dumber and certainly not as good for his Q rating. So he started doing New York theater again — notably God of Carnage opposite James Gandolfini. People like Sorkin noticed. People like Gandolfini told Daniels to get over his lifelong aversion to television. One night, after a Carnage performance, Daniels ran into his old friend Busfield, now a Sorkin regular and sometime producer, who’d been after him for years to do TV. “Come with me,” he told Busfield. “I’m ready.”

He and Busfield came up with Happily Ever After, a dramedy set in Michigan in which he’d play a laid-off middle manager who becomes a touring musician. Showtime outbid HBO for the rights to the series, but when they stalled, Daniels says he gave them an ultimatum: “If you don’t want it, I’m gonna do some kind of series somewhere, because the movies have dried up.” Sorkin hired him soon after, and Showtime responded with an offer to order Happily Ever After immediately. Daniels decided to stick with The Newsroom and said no.

When Daniels first met Sorkin and producer Scott Rudin to talk about The Newsroom over breakfast at the Four Seasons, “the one thing they asked was, ‘Can you get angry?’ ” he says. “Basically, ‘Do you have the balls to go there?’ ” To show them he could, he didn’t point to an old part. Instead, he dug deep and reenacted two occasions on which he himself had lost control. One tantrum was aimed at the producers of Gettysburg; he won’t say what the other was. “Aaron, who’s not big on confrontation, was like, ‘I got it, Jeff, I got it.’ ” Emily Mortimer, his co-star, says, “I think there was something in Jeff that really related to that sense of being held back, that grumpy-old-man-type thing — but at heart a romantic. Jeff just understood that person.”

Winning the Emmy for The Newsroom meant everything. “I’m still going through that,” he says. “The relief.” But two days later, he was in Atlanta, sloshing his brain around for the first take of Dumb and Dumber To. I suggest it might have been a difficult transition to make, just after being publicly celebrated for maybe the most complex role of his career. Daniels tees up another story. He remembers visiting Iraq War veterans at Walter Reed hospital — Dumb and Dumber fans to a man — and distracting them from brutal injuries by exchanging the stupidest bits of dialogue. “It has value,” he concludes. “It’s escapism. It’s one of the few things this country still manufactures.” I tell him that sounds like something Will McAvoy would say. “Well,” he says, “it’s true.”

*This article appears in the November 17, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.