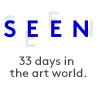

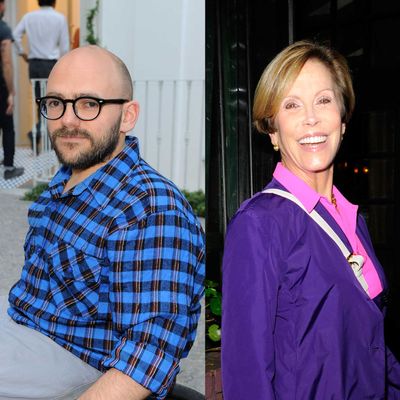

On an ice-cold morning last month, art adviser Thea Westreich tried to woo Ryan Gander. ÔÇ£He called me up and asked me on a date, and I said I was married,ÔÇØ she joked of her first meeting with the British conceptual artist, who came to the city to accept an honor at the New MuseumÔÇÖs Next Generation fete (ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm in town for some dinners,ÔÇØ he told us modestly).┬áFor his last day, the artist decided to give Westreich ÔÇö who is, in truth, an old friend ÔÇö a shot at nabbing him as a client. Westreich arrived to the Upper East Side via black car wearing a quilted parka, her blonde hair neatly bobbed, to find Gander, in plaid and a puffer vest, already deep in conversation with her current client, Grant Henegan, a collector and businessman in town from North Carolina looking for his latest find.┬áOn the agenda were visits to Skarstedt, Dominique L├®vy, MoMA, and Fergus McCaffrey for some Oehlen, Polke, Gober, and more, as Gander observed adviser and advisee. In a nod to Gander, we present a script from the day.

Act One

Per Skarstedt

20 East 79th Street

New York, NY 10075

Introductions

Grant Henegan: IÔÇÖve an eager eye to see what you pick up today.

Ryan Gander: HeÔÇÖs the real collector. IÔÇÖm just observing.

GH: So to manage your work, youÔÇÖve got to be able to produce the art, manage your career, manage it commercially, and in your case particularly youÔÇÖve got a lot of people producing in your studio for you.

RG: Yeah, itÔÇÖs strange. Whatever amount you earn, you donÔÇÖt just keep the money ÔÇö with the studio, itÔÇÖs extraordinary. And when you see the tax return at the end of the year, IÔÇÖm like, ÔÇ£How did we spend that much money? What did we make, cars?ÔÇØ

GH: How many works did you make last year?

RG: I made 324. We have a really accurate database.

GH: And you have someone from your studio keeping track of where it is, who got it, and once it goes to the gallery 

RG: No, see, we do it differently. We donÔÇÖt have a main gallery or anything. We run it as a business so we allocate works with an allocation fee like a gallery would consign a work to another gallery. It has to be returned within six months if itÔÇÖs not sold and the price is fixed. The amount of discount given has to be fixed, the gallery absorbs any further discount. You just lose track of work. There was a point ten years ago where I was making, like, 60 works. Just had no idea what we had anymore. My studioÔÇÖs in London, and then I have another one in Suffolk near home, in between a nuclear power station and a dog-food factory. Very romantic.

The Setup

Thea Westreich: So the reason that weÔÇÖre doing this is that IÔÇÖm trying to get Ryan as a client. I already have Grant as a client. What we typically do is allow a lot of space in terms of what the client sees in advance of their selecting a way to go forward: how theyÔÇÖre going to collect, what theyÔÇÖre going to collect, and why. We would do this with Grant with or without trying to capture RyanÔÇÖs interest.

RG: I hadnÔÇÖt thought about that.

TW: Yes, this is what we would be doing with Grant in any case. The reason weÔÇÖre coming to Oehlen is because weÔÇÖve talked about people like [Michael] Krebber and Merlin Carpenter ÔÇöpeople who emerged in the early 1980s in Cologne. Per has a particularly good secondary market eye, and he collects almost always when he gives a show like this.

On when you encounter a master:

GH: Yeah, having just seen the Polke show in London [at the Tate], you get it.

RG: Amaaaazing.

GH: WasnÔÇÖt that a great show? A walk-through of a life.

RG: It shook me up a bit.

TW: Yeah?

RG: I thought I should have been an electrician or something else. I had the feeling I wasnÔÇÖt good enough.

TW: Well, with that show, with the two of them ÔÇö Malevich and Polke in one ÔÇö I mean, youÔÇÖd have to give it all up. Anybody would. But I have faith in you, baby. I wouldnÔÇÖt give up on you.

When one is enough for the collection:

TW: Do you have a favorite? [They regard the Albert Oehlen paintings.]

RG: I think youÔÇÖd need more than one.

TW: Of these?

RG: No?

TW: If I were thinking about if I did want to collect another, I would want a painting but from a different expression of his because theyÔÇÖre all various and theyÔÇÖre all very, very good. For example, thereÔÇÖs a black-and-white series of paintings that are very good. When you start with buying younger artists, like, for example, we did ÔÇö you go in and you buy your first Christopher Wool ÔÇö and youÔÇÖre really invested, you keep going, until the price points get out of hand, and then you start with something else. You want an evolution of AlbertÔÇÖs paintings to have an important collection.

Act Two

Dominique L├®vy

909 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10021

On whatÔÇÖs really happening when people gift works to museums:

RG: [He is recounting the prices from Per Skarstedt]: 1.1 million, 800,000, 600,000  thats like 3 million, and 15 percent at the secondary market 

GW: I donÔÇÖt understand the commercial model because they all do it: Gagosian does it, Zwirner does it, they all seem to do these historic exhibitions with nothing for sale!

TW: In this case, theyÔÇÖre probably not for sale. That may or may not be true: It may be in collections that Per has already built or that heÔÇÖs already sold to. Did you hear them say that somebody bought it as a gift for MoMA? Well, now the dealers with work thatÔÇÖs very hard to get, that has high currency in the market, theyÔÇÖre saying, ÔÇ£Oh, IÔÇÖm sorry, weÔÇÖre only selling to people who are giving their work to institutions.ÔÇØ

RG: IsnÔÇÖt that a conflict of interest?

TW: Of course it is.

RG: Because then it puts pressure on the museum to do a retrospective of that artist, which will increase the prices in their collection, and theyÔÇÖre the trustees of the museum, and itÔÇÖs all a big circle of deceit.

TW: No one knows how to get out it. No one. IÔÇÖve seen patrons in museums talking to curators telling them to raise and lower paintings, or fix the lights. ItÔÇÖs an astounding thing to witness. But the big thing I say to everyone with whom we work is great art is great art. Sooner or later the rubbish goes to the rubbish cans, and the great art stays in the forefront of history.

On taking things slow when it comes to building your collection:

TW: Collecting is an incredibly interesting experience if you do it the way Grant is doing: learning, taking the time to look at things, making decisions emphatically when they need to be made.

RG: I always felt that collecting is a bit like  in the same realms of panic. You know what I mean?

TW: Ummmm 

RG: If I was collecting now without you here, I think IÔÇÖd just be running around like headless chicken going, ÔÇ£Fuuuuuuck!ÔÇØ

TW: You would be.

RG: Well, thatÔÇÖs the thing is that now IÔÇÖm really relaxed. YouÔÇÖve unfolded the whole of art history in front of us, and weÔÇÖre looking at one little swatch, and now weÔÇÖre going to look at another swatch. Which is a nice way to think about collecting, isnÔÇÖt it?

On supporting young artists ÔÇö even when itÔÇÖs ugly:

RG: I have a merely ethical and moral relationship to collecting.

GH: Moral?

RG: A moral and ethical relationship to collecting, whereby I never collect things that I necessarily like. I collect things by young artists who donÔÇÖt have any money because I need to give them some money! Because I think that they should carry on whether I like it or not.

TW: See, I have the opposite feeling: I think you should give to artists you really believe in, so that they can continue to give the world 

RG: ThatÔÇÖs what I do, but itÔÇÖs kind of like the idea of being swayed by aesthetics of beauty for your collection. Because sometimes buying the ugly work is the thing that you know you should do.

TW: Ohhhh.

G: WeÔÇÖve all learnt that!

TW: ThatÔÇÖs for sure!

G: Ugly is good!

TW: Absolutely.

RG: You see the practice of an artist and want to better them and further their career and know that currency could enable them the time and space to make more work. But. I might not actually like the work. And I think thatÔÇÖs really important, like when I do selections for shows, like prizes.

TW: Yeah, but Ryan, if you start to really collect with a vision, what you say is ugly is by somebody elses eye. Its more that you recognize that theres something significant being done and that it interests you, and you may not know all about it, but it does draw you into the room. I mean, I hardly know all about your work and Ive been looking at it for

RG: ItÔÇÖs less to do with it being ugly than IÔÇÖm not buying it for myself. IÔÇÖm buying it for them.

On a possible sale at Dominique L├®vy:

TW: HereÔÇÖs an artist, for example, who is not highly recognized in the international world, Antek Walczak. WeÔÇÖre very eager for Grant to buy this work. HeÔÇÖs a major figure in the young art world. I can never describe his work adequately, but two of his works are available. Remember, this is post-internet art that weÔÇÖre looking at.

RG: Is it?

TW: Yep.

GH: IÔÇÖve got two already.

TW: HeÔÇÖs got the American version thereof.

RG: But I like this.

Act Three

Afterward

The verdict:

RG: I always say artists must broaden their research. I go to casinos, fly fishing, to show apartments in new residential buildings, watch fairs, the football, ikebana courses, survival expeditions, Dungeons & Dragons nights, and it doesnÔÇÖt matter which of these I personally want to do ÔÇö that is my job. ThatÔÇÖs true research; otherwise, it would be a bit like masturbating. My fantasy art collection day was part of this diverse research.

I wasnÔÇÖt taken to anywhere I would have gone if I was alone. An ÔÇ£I know what I likeÔÇØ mentality is hard to shake, but of course appreciation has space for being challenged. I think thatÔÇÖs what Thea and Ethan are awesome at: listening and then turning collectors upside down and shaking them, then listening again when theyÔÇÖre back on their feet.

TW: Grant acquired the Antek painting, which is the third of Anteks work in his collection. He is also interested in Sam Lewitt, but the piece he wanted had already been sold  Ryan is more likely to make a work of art about the event than we are to get him as a client.

RG: I would love to go to the auctions with Thea once also, if sheÔÇÖll have me.