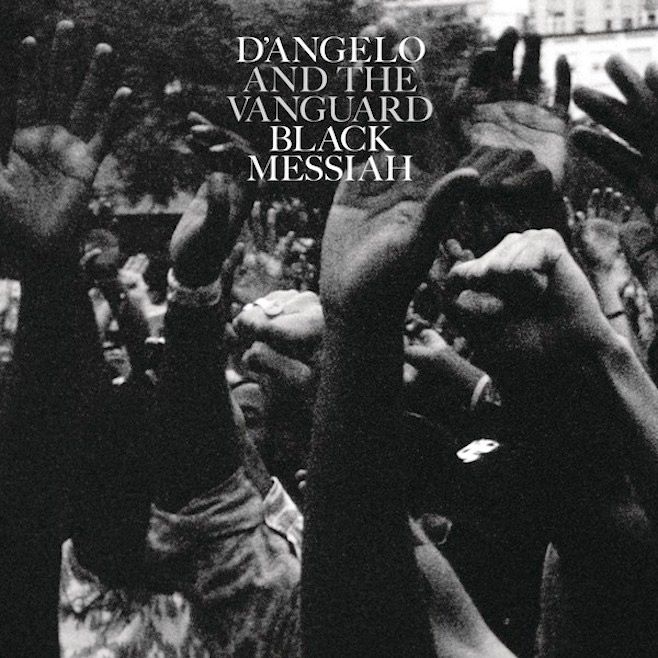

“Everyone around him knows about D-time,” GQ’s Amy Wallace wrote in a 2012 profile of D’Angelo, “a pace so slow that it could test even the most patient saint.” Fans knew about it, too: For nearly 15 years, they’ve been waiting for the second coming of D’Angelo, in the form of a promised follow-up to his 2000 neo-soul masterpiece, Voodoo. Recently, though, D’Angelo’s notorious internal clock kicked, quite unexpectedly, into fast motion. Inspired by protests over the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, D’Angelo and his label RCA reportedly rushed the release of his third album, Black Messiah (which they claim was slated for “early next year” — a refrain D’Angelo fans are used to by now). This kind of immediate action and blind trust in artistry is all but unheard of in today’s risk-averse major-label game; reportedly, some RCA employees did not even hear the album until Sunday night, when it was released on iTunes. We all knew that if D’Angelo’s comeback was ever going to happen, it would be boldly on his own terms — but it’s safe to say we didn’t expect them to be this bold.

When we talk about D’Angelo’s absence, we are not just talking about D’Angelo. We are talking about the particular burden placed on black genius in the 21st century; we are talking about Lauryn Hill and Dave Chappelle, as well as D’Angelo’s generation of neo-soul luminaries, like Erykah Badu and Maxwell. All struggled with the strange tensions that arise from mainstream success in a culture that is too often in denial about the fact that it is still intrinsically racist. All confronted the question of whether continuing to make successful work in that culture is a form of assimilation; most seemed to find the answer to be yes. Rather than become symbols, icons, or deliverers of some kind of clearly decipherable message, most of these artists chose to walk away. They chose silence — the kind of silence that, only if you’re listening closely enough, is its own protest song. “Black stardom is rough,” Chris Rock mused in that GQ piece. “If you’re a black ballerina, you represent the race, and you have responsibilities that go beyond your art. How dare you just be excellent?”

Calling this record Black Messiah feels at once bombastically earnest and slyly self-aware. D’Angelo is attempting to rise to the occasion while also acknowledging the burden of having to. The second track, “1000 Deaths,” opens with the sampled voice of a preacher. “When I say Jesus,” he intones, “I’m not talking about some blond-haired, blue-eyed, pale-skinned mother-milk complexion cracker Christ. I’m talking about the Jesus of the Bible, with hair like lamb’s wool.” The congregation goes wild. This is the sort of fiery, direct rallying cry we expect from a man assuming the mantle of Black Messiah in times of chaos. But then, when D’Angelo himself arrives on the track, his voice is muffled. Murky. It floats in and out, locked in the song’s hypnotic groove but occasionally drowned out by the bass line’s low boil. The contrast between these two voices, the two ways of addressing the listener, could not be more pronounced. One delivers a clear message that can be understood immediately and turned into a call for action. The other beckons you to come closer, listen harder, now listen again.

Another story we tell when we talk about D’Angelo is one we usually only tell about women: his resistance, in the wake of the iconic “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” video, to becoming a sex symbol; his frustration with the ensuing onstage cat calls; his need to assert himself as something more complicated than a body. (He addresses it with playful, if uncharacteristic, directness on “Back to the Future, Part I”: “So if you’re wondering about the shape I’m in / I hope it ain’t my abdomen that you’re referring to.”) And even more than the sprawling but sometimes hooky Voodoo, the structures of these new songs play around with the deferral and very occasional fulfillment of desire. The single, “Sugah Daddy,” occasionally feels like it will build to some kind of James Brown–shrieking catharsis, but in the end seems perfectly content taking a slow, jazzy stroll around a syncopated piano riff. The sighing, Spanish-guitar-driven ballad “Really Love” is the closest thing Black Messiah comes to an outright declaration, but even then it’s muttered, personal, and intimate — “I’m in really love with you” — as though he feels the emotion too deeply to raise his voice above a flutter.

Black Messiah has a confident faith in the patience of the listener, and for all its sonic kinship with Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, this feels like the most retro thing about it. Never content to be an easily legible symbol of anything, D’Angelo has made an album that does not reveal all of its secrets on the first listen (or even the tenth). In this age of surprise album drops and instant, knee-jerk judgment, pretty much every headline this week has told us, in nearly identical terms, that it was “worth the wait.” I’ll add my voice to the chorus, and while I don’t think it quite reaches the heights of Voodoo, I’m looking forward to seeing what sort of hidden pleasures it reveals over the long haul. Maybe that was the secret logic of D-Time all along: Black Messiah finds D’Angelo making music that speaks, however obliquely, to the moment, but that also invites you to look beyond it, behind it, and at its most transcendent — above it.