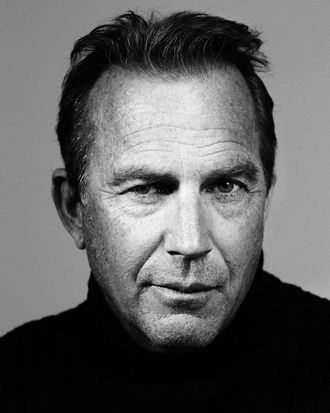

Kevin Costner sidles into a West Hollywood hotel room at precisely noon. After making about 50 films and winning two Oscars (for Dances With Wolves, the movie he directed and produced a quarter-century ago), he knows when he’s on the clock. He gives every appearance of being the Joe Regular you expect, the Western-movie star of his era. Sun-bronzed, rugged face, camel-color Levi’s, cowboy boots. He supposes they’re Lucchese. “You’d have to ask my wife,” he says. “She bought them. The only thing I know about clothes is how to put them on.”

So it’s disorienting to hear Costner — the environmentalist and booster of Native American cultural history — hurl the term “street nigger” onscreen. In his new biracial-custody-fight drama Black or White, that phrase is employed by both black and white characters. Its presence in the script by writer-director Mike Binder may have been a red flag for investors, and Costner had to bankroll most of the movie himself. “One of the reasons I financed this film is so the script that I read — the script I just could not ignore — would not become a casualty of conventional moviemaking,” he declares. “If we back away from using that word that so many of us have used — and maybe not always in anger, but also in ignorance or in a joke or in a time that is no longer appropriate — then we lose a lot of the drama. So much of what movies are about is what the people in them get to say. So it had to stay.”

That defense is pure Costner, the latest in a career built on soliloquies spoken by sensitive manly men: the lone athlete, gunslinger, politician, Robin Hood, Pa Kent. He’s not an ironist, although, when accepting a recent Critics’ Choice Lifetime Achievement award, he did joke that he’d wandered onto “a list of actors of a certain age that happened to be in town.” It’s hard to picture him not being earnest: Think of perhaps his most famous moment, the monologue that seduced Susan Sarandon’s character — and a sizable part of America’s female population — in the 1988 baseball film Bull Durham. That proclamation began with “I believe in the soul, the cock, the pussy, the small of a woman’s back, the hangin’ curveball, high fiber, good Scotch,” and wound up with “I believe in long, slow, deep, soft, wet kisses that last three days.”

In this decade, Costner has been trying his hand at character roles in franchise films (lately Man of Steel and Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit) and a Luc Besson shoot-’em-up (3 Days to Kill). This fall, he’ll also become an author, with an adventure novel called The Explorers Guild that’s intended to inaugurate a series. With Black or White, a “little film,” as he calls it — shot in 26 days on his $10 million budget — he’s going from rugged dad to, for the first time, grandfather. “But a young grandfather, in case you didn’t notice,” he says with a flash of that wolfish grin. He takes a sip of room-service tea. Yesterday, he turned 60.

Was there a birthday blowout? “I’ve had enough attention for a lifetime, and I didn’t want a party,” he replies, “but my wife and oldest daughter wouldn’t have it.” So there was a bash at the oceanfront Coral Casino in Santa Barbara. “My daughter gave me a treasure chest containing 60 letters. She said, ‘Curl up with them, these little whispers of what your friends and family feel about you.’ ” Some of his children — he has seven, ranging from age 4 to 30 — toasted him. “It was very moving,” he says. “You go from wondering if they can cross the street by themselves to listening to them talk about you in front of hundreds of people.” He likes working with kids, too, he says, and remarks that one of his favorite performances was in A Perfect World, the 1993 Clint Eastwood film in which he plays an escaped convict who befriends the boy he has kidnapped. The following year in The War, he played a Vietnam vet struggling to teach his combative son, played by a young Elijah Wood, what’s worth fighting for. “I will get emotional talking about this,” Costner says, his voice breaking as he looks away and swallows hard. “But The War is the only movie my father can’t watch. The role I play reminded him so much of his dad.”

Costner casts his own life in cinematic terms. His paternal grandfather, who lost everything in the Dust Bowl, “was Tom Joad,” and his wife “ran money for Bugsy Siegel.” The actor’s own parents, Sharon, a welfare worker, and William, who worked for the electric company, gave their baseball-obsessed son “a Huckleberry Finn childhood” of tree houses and camping trips. During high school, the Costners moved every year, and Kevin was a John Hughes–style outcast — always the newest, shortest kid in his class. “I had plenty of confidence until I got my driver’s license and passed it around and girls said, ‘You’re only five-foot-two!’ ” He did a lot better once he sprouted up to six-one.

In Black or White, the intergenerational drama begins on the worst day ever for the well-off Brentwood attorney Elliot Anderson (Costner). His wife has just died in a car crash, leaving him to raise his beloved granddaughter, Eloise (Jillian Estell), the biracial offspring of his teenage daughter, who died in childbirth. As the grieving widower, Costner fumbles awkwardly doing simple things like brushing his little girl’s hair and tying a bow in it. “This is a stark reminder of what men hand over to the women in our lives and what is going to be in front of him,” he says. “And then, of course, this little girl tells him he’s doing it all wrong.” Costner laughs, leaning forward to deliver a punch line, “That the way he tied the bow is like a tennis shoe.”

As if on cue, his phone rings, and his wife, Christine, is calling to fill him in. (The ringtone is a guitar twang from his country-rock band, Kevin Costner & Modern West.) Their son had been sick that morning; after “eking out as much time with him as I could,” Costner had left the house in a hurry. Has he packed properly for the film’s premiere tonight, Christine asks? “I brought my big folding bag with everything I need,” he replies. “But bring a backup suit.”

Black or White’s Elliot is disheveled and boozy, a sad and angry shell. A custody battle for the granddaughter ensues, pitting Anderson against her grandmother, Rowena (Octavia Spencer). “The possibility of Elliot losing this little girl — the last connection to his wife and daughter, the two women he loved the most — puts him off balance, riding grief in a fog,” he explains. Does it get ugly? “It is raw,” he answers, “but does not lack for a sense of humor. Broken people say awful things and do incredibly absurd things.”

Costner made a point of taking the film to St. Louis for a screening. “Some people said maybe not now — but isn’t Ferguson us?” he says. “I saw a family on CNN.com whose restaurant was in danger [of being vandalized], and I read a cool story about a biracial couple with a biracial son, and I said, Why don’t you come to the movie?” The Cardinals’ former shortstop Ozzie Smith came along, too, a gesture to Costner’s Bull Durham and Field of Dreams fame. How’d it go? “Black and white, they applauded,” he says. “People get it. And that’s what I make movies for — for people.”

*This article appears in the January 26, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.