“Who says that? What if it turns into something good? I can’t let that happen!” Larry Wilmore laughs as he recalls one of the few career what-ifs he still wonders about. It was 1991, and he had just decided to move on from a decent but stalled career as an actor and stand-up comic to the uncertain but slightly more practical world of television writing. Within the first nine months of his new gig, he got two calls to appear on Seinfeld. He desperately wanted to give acting one last go, but each time he turned it down. “It would have changed the whole direction of my career,” he says. “But I’m glad it happened the way it did.”

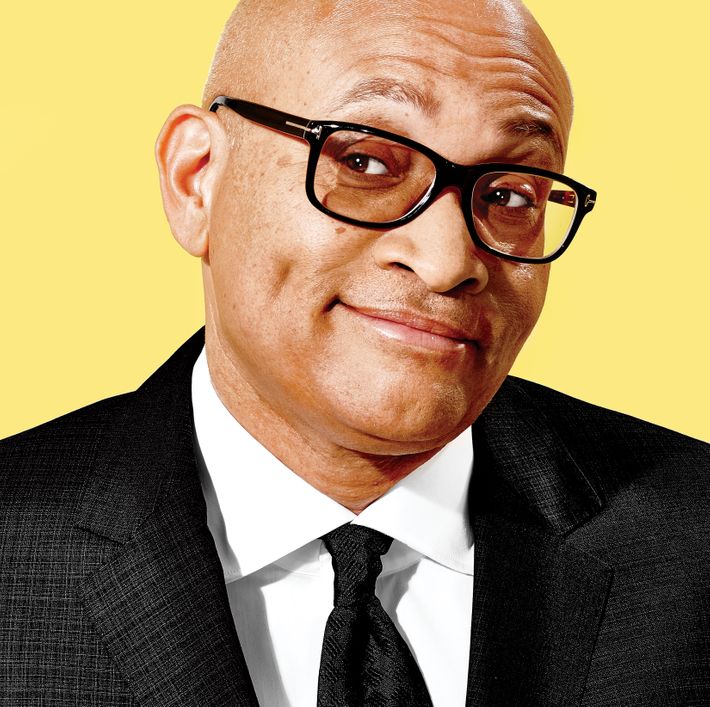

That’s because it’s all happening according to his secret, decades-in-the-works plan. Formerly the Senior Black Correspondent on The Daily Show, the 53-year-old Wilmore will host Comedy Central’s upcoming Nightly Show, heir to the 11:30 p.m. spot vacated by Stephen Colbert. It’s early November, a little more than two months before The Nightly Show’s January 19 debut, and I’m trying my best not to get lost in its mazy, makeshift office in Hell’s Kitchen. When The Colbert Report packs up shop in a few weeks, the staff will move to their permanent home a few blocks away. But for now they are like a rebel encampment on an unused floor of a CBS-production high-rise. Offices double as storage; someone else’s posters line the hallways. Everything is so fluid that, up until yesterday, The Nightly Show was still called The Minority Report, the name that was announced when Wilmore got the job in May.

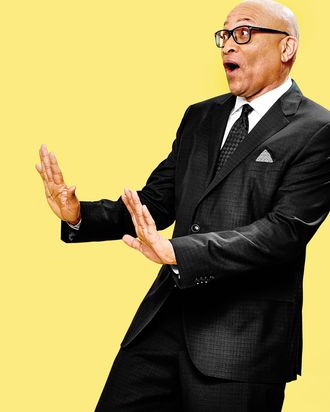

Wilmore has an unusual kind of fame, the kind where people walking down the street might recognize him from The Daily Show but not know him by name. The Nightly Show’s first promo clip plays up his seeming anonymity. In it, he patrols a late-night eatery, warmly pitching himself and his new show to skeptical, confused diners. The Nightly Show’s conceit is fairly simple: It’s a news show from the perspective of the underrepresented. Besides Wilmore’s monologues, there will be a mix of panelists and recurring players, taped on-the-street segments, and interviews. What Wilmore essentially wants to get at are broader questions of power and powerlessness, the gap between the CEO and the minimum-wage worker: “I look at it in terms of top dog and underdog,” he explains. “Underdog gets to make fun of top dog, but top dog can’t make fun of underdog. But guess what you get, top dog? You get to be top dog.”

When Wilmore talks about The Nightly Show’s self-consciously “underdog” identity, he could just as easily be talking about the long arc of his own career. He grew up in a Catholic household in Pomona, a mostly middle-class suburb about a half-hour outside Los Angeles. His childhood was fairly mellow, full of sports, sitcoms, and family-room skits he would stage with his younger brother, Marc, now an Emmy-winning writer with The Simpsons. In the early ’80s — inspired by his father, who had left his job as a probation officer and began studying medicine in his 40s — Wilmore dropped out of nearby California State Polytechnic University and started performing at the Mark Taper Forum in L.A. He figured he, too, could simply become a doctor if nothing had panned out by his 40s. He pieced together a decent career as a performer, back in the days when a Star Search appearance or a recurring bit on The Facts of Life (he played a police officer) were enough to book a steady stream of stand-up gigs.

There’s a clip on YouTube of Wilmore doing stand-up on Comic Strip Live circa 1990. His act feels smooth and genial, calibrated to an almost bashful knowingness. Even when he makes an acerbic joke about “white slave masters” or rehearses an uncomfortable, Mickey Rooney–esque bit about a Chinese man playing an epic game of Wheel of Fortune (“I’d rike to buy another vower”), his calm, understated style makes it all seem rather tame and unthreatening. He hams it up as he talks about being light-skinned, quipping, “I just tell people, ‘Look, if I was a beer, I’d be a Negro Lite — and I am a third less angry than the regular Negro!’ ”

It’s easy to watch this clip now and recognize the challenges Wilmore would face in the early ’90s with the ascension of swaggering, raucous, hip-hop-influenced shows like In Living Color and Def Comedy Jam. It’s not that his sense of humor was at odds with those boundary-pushing upstarts; it was in his demeanor and delivery. From a casting perspective, black culture got collapsed into a limited range of brash archetypes, none of which suited the easygoing Wilmore. “They weren’t interested in my type.” It was strange, he says, to admire these shows from afar, knowing that they were having an adverse effect on his career. “At that point I knew Hollywood wasn’t going to find me. I needed to be able to control my own destiny. Being an actor was too flighty.”

He decided to try writing and producing, no matter who came calling. In 1990, he got a job writing jokes for a short-lived late-night talk show hosted by radio DJ Rick Dees. His second gig: writing for In Living Color. “The irony was I couldn’t audition for it, but I could write for it.” Wilmore hopped from show to show, seeking out new opportunities that would enhance his storytelling skills. The relentless grind of In Living Color taught him to be fearless about pitching ideas. Writing for Sister, Sister and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, he mastered the structure of the family sitcom.

In 1999, he co-created the bawdy animated series The PJs with Eddie Murphy and Steve Tompkins. In 2001, he created The Bernie Mac Show, one of the decade’s most brilliant and avant-garde shows, winning an Emmy for writing the pilot. Last year, Wilmore was hired as the showrunner of Black-ish, the highly rated ABC sitcom starring Anthony Anderson and Laurence Fishburne, a job from which he resigned when his dream gig opened up. “This was an opportunity that, ever since I started writing for Rick Dees, I was working toward,” Wilmore says, gesturing around his temporary office. “This was the destination. Having my own thing.”

A month later, I’m back at The Nightly Show to observe a pitch meeting, as the writers and producers refine the show’s voice by riffing through the week’s events. Today’s menu: torture, undercover cops, Bill Cosby, Sony, and the pope supposedly decreeing that dogs can go to heaven. About 30 writers and producers crowd around a table; a few others sit in the hallway just outside, craning their necks to get a look whenever someone says something especially riotous. Wilmore sits at the front of the room. Behind him, Nightly Show head writer Robin Thede commands the dry-erase board, jotting down riffs and assignments.

It’s a noticeably diverse room, and there’s a range of personas: Some laugh out loud and slap the table; others sit with arms folded, thinking, whispering permutations of a punch line to themselves until it’s ready for a full-throated test run. The vibe is charitable, democratic. Wilmore and the writers talk through process, staging, strategies for building skeptical, brows-raised pauses into their scripts; it’s like watching teammates work out where they want the ball delivered. Jokes are stretched to their limit, folks adding a minor tweak here and there until it’s down to two writers playing a friendly game of one-on-one. There is a brief discussion about rectal feeding and the absorptive properties of the anus. Thede’s voice booms over the din as she gamely corrals everyone back on track. The room works through a fantastic gag involving a controversial guest who doesn’t want to appear on-camera; he asks for his face to be blurred onscreen. Wilmore adds a clever wrinkle: What if they blurred out the terrified host’s face as well?

It is late on a Friday afternoon, yet it doesn’t seem like anybody is going home anytime soon. As they nail down the final assignments for the mock show they’re staging the following week, Jon Stewart, creator and executive producer of The Nightly Show, slides into a chair next to Wilmore at the front of the room. Stewart surveys the board of ideas. He seems pensive, grave, not because he’s concerned but because he seems to revere and cherish the work going on in this room. Wilmore rehearses the highlights of the meeting for Stewart, refining a lot of the jokes on the fly. He talks about how they can use the wild and absurd to get to the serious, before destroying the room with an impression of Fat Albert admonishing his creator Cosby. “Hey, hey, hey,” Wilmore grunts, “rape’s not okay.”

Even though Wilmore always knew he wanted to host his own show, he didn’t feel ready to do so in the mid-aughts. He started performing again, most notably as the diversity specialist Mr. Brown on The Office, for which he also consulted. In order to host a talk show, he knew he had to learn the rhythms of live interviewing and audience interaction. He began hosting panel discussions and testing out new stand-up formats. He secured a meeting with Stewart in 2006, just as The Daily Show was recruiting a new crop of correspondents. Stewart quickly learned to trust his new hire. “Jon always calls me the adult in the room,” says Wilmore.

Other than Wilmore’s appearances on The Daily Show, he’s offered a few clues as to how he’ll approach The Nightly Show. In 2009, he published a book of faux punditry called I’d Rather We Got Casinos: And Other Black Thoughts (sample bit: What if black people rebranded themselves as the “chocolate people”? “Who doesn’t love chocolate?”). Three years later, he hosted Larry Wilmore’s Race, Religion and Sex, a pair of Showtime specials that were half stand-up, half town-hall meeting. He’s cultivated a way of broaching difficult subjects with a bemused mock-innocence, as when he playfully decried all the “shitty white people” during a remarkably rancor-free Daily Show segment on Ferguson.

The job of Wilmore’s writers is to figure out what they can do with his unusual range. As Thede explains to me a couple of weeks later, this is where the eclectic diversity of The Nightly Show staff becomes crucial. “I’d say in general having a room full of people of all different backgrounds — not just race, not just gender, but political background, life experience, economic background — it helps us have those real conversations.”

Wilmore doesn’t traffic in the righteous exasperation of Stewart or John Oliver — and one wonders if he would be in this position at all if his vibe were more indignant and outraged. He’s not playing a character like Colbert. Even if he wanted to, viewers would probably have a harder time recognizing that in the way they quickly mastered the premise of a fake Bill O’Reilly. “The fact of me being there sure makes it about race in some way, but that’s not what the show’s about. We’re not doing a race show or 30 minutes of Senior Black Correspondent. It is me doing a show the way Jon Stewart does his show.”

In other words, the show will succeed as soon as viewers realize that underdog isn’t purely code for race, though that will clearly be part of it. If Wilmore’s body of work (and career trajectory) offers any indication, this will be a show that resists cynicism, searching instead for moments of humanity or humor, even in dire situations. He wants the show to be premised on discovery, not opinion. This is why the question of tone will be so crucial. After all, it’s easier to shout than to use the scientific method. Given the polarization of contemporary politics, will America take to Wilmore’s thoughtful, even-keeled brand of self-professed “passionate centrism”?

“I realized early on that I have to do the things that are going to bring me fulfillment; otherwise, you can get burned out very quickly, you can get eaten up,” he says. Though there’s a light fray to his voice when we speak for the last time just before Christmas, he seems remarkably prepared for the months to come. He is largely unfazed by the pressures of following Colbert or the fact that he is unusually old to be making his talk-show debut. His concerns are more immediate: how to pace himself throughout the day so he remains fresh for taping, how to manage a bicoastal life while his wife and two children remain in L.A. “People say, ‘Why do you write?’ And I say, ‘Because I have a deadline.’ I’m not a romantic writer. I come to work, I start writing. That’s how it works. And when I’m done, I go home and I don’t write. Making people laugh is an expression for me more than anything else. If I was working at a bank, I’d still be making people laugh. I may not last long at that bank, but I’d still be doing it.”

*This article appears in the January 12, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.