I have places inside me where there are works of art: internal abysms that feel full, physical, like forces that fuse past and present. In the early 2000s, I spent four straight days in the Prado; all of itÔÇÖs still within me like some huge, Proustian madeleine. Almost every Bosch, C├®zanne, Matisse, Alice Neel, Bill Traylor, Mart├¡n Ram├¡rez, and Marsden Hartley that IÔÇÖve ever seen can flash like lightning at will. I spent a day enraptured by Matthias Gr├╝newaldÔÇÖs┬áIsenheim Altarpiece┬áin Colmar. (I still wonder if I became invisible that day, when guards silently allowed me to remain in the museum while it closed for its two-hour lunch.) I have a psychic zero-point for all the Seurat drawings IÔÇÖve ever seen, and at the center of this point is the small Giovanni di Paolo in Chicago that I saw when I was 10 years old, which set me on the course of my life ÔÇö the genesis moment when I understood that paintings werenÔÇÖt only things to be┬álooked at┬ábut are objects that┬ádo things.

Among these and the other inner alpha points, these particular paintings made my inner trees fall and are in me always, churning. What I gleaned from them was so paradigmatically extensive that it recalibrated almost everything I knew about art. Even though this internal lightning is always with me, it went bioluminescent a few months ago, when paintings found on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia were estimated to have been made 40,000 years ago. ThatÔÇÖs 10,000 years older than the oldest cave paintings in Europe (in the Chauvet Caves). Not long before that came reports of decorative beads and mixed pigments dating back more than 75,000 years. Not to mention the deliberate, delicate symmetries in newly discovered stone axes made 100,000 years ago by an entirely different and extinct species: Neanderthals. (ThereÔÇÖs evidence that Neanderthals also built and sailed watercraft; there are Neanderthal stone cleavers that date back 170,000 years.) How could I not use these revelations to relate my own come-to-cave-art moment?

In 2008, my wife and I spent a week driving through the stunning Spanish Pyrenees looking at small Romanesque churches, often alone, with no tourists around. I knew there were Paleolithic caves nearby in France, so before we left New York, I booked a time slot for a group tour inside the Niaux Caves. We crossed the Pyrenees, and after being horrified by hordes of European shoppers who come daily to Andorra for tax-free goods, we passed into a chasm that became a deep mountain gorge. The Niaux Caves are located at the southern mouth of this valley. I imagined that even 13,000 years ago, this would have a place with a constant source of fresh water, an abundance of raw materials, fish, game, a perch from which to observe herds and watch for invaders, and a view to die for.

We parked in large lot. I began hearing something I hadnÔÇÖt heard for a week: English. Scads of European families and Americans with fanny packs and kids were all around. (I later learned the lot mainly served day hikers and a nearby park.) Soon about 15 of us met in a pre-designated spot near the entrance to the caves. We were greeted by our guide, a 20-something art historian from Paris. She handed each of us a small flashlight and explained that these would be the only source of light on our trip inside the caves, and that we were to stick together in a single-file line until we got to ÔÇ£the gallery.ÔÇØ

Ducking low through a small opening in the stone, we passed into darkness. The caveÔÇÖs original, much-larger entrance had been elsewhere and, along with an enormous overhang, had collapsed millennia ago, sometime after the last ice age. Presumably, these caves were originally not entirely dark, as light was able to flood in. In any event, itÔÇÖs thought that this entry opened sometime around 1600. My wife and I stuck close to the guide as she lectured. Already something was happening to me. I loved being in this subterranean world, feeling the atmospheric pressures change, noting the sounds of the world fading, new humidities, air currents and sounds appearing, seeing walls undulate. I felt grateful to be here, and very close to my wife and to our guide. I wasnÔÇÖt afraid to be here, but I was aware that I was not only in an alien world, but something alien inside me was awakening, and my senses were sharpening in strange ways.

After walking for a while, feeling my interior world intensify, we stopped, and our guide said, ÔÇ£Please gather around me. We are about to enter the gallery. Stick together. Do not touch anything or leave the path. Please hand me all of your flashlights. I will have the only light in the gallery.ÔÇØ I had an instant of wanting to hide my flashlight so as to use it to see better. As I handed my light to her, I sensed she knew that this moment produced apprehension, as she smiled at each of us reassuringly. Like two kids, my wife and I huddled on either side of the guide, walking another 200 feet in total silence, until we came to what felt like a large, irregularly shaped cavern. I can still feel cool currents on my face. We were in the ÔÇ£Salon noir.ÔÇØ Everything remained silent; our guide pointed her light to the ground so our eyes could adjust. After a moment, she wordlessly shined the beam upward. A never-ending clap of thunder sounded inside me; one reality was replaced by another. I will try to recount what I saw next and what it made me think.

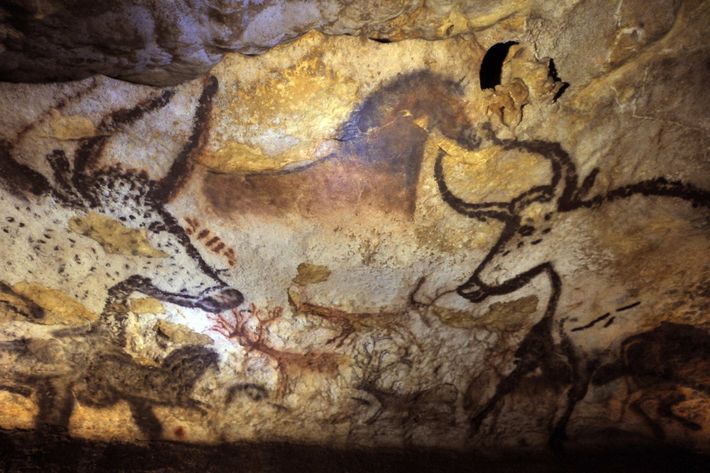

We were in an amphitheater with images all around us. Of individual animals and groups of animals. Bison, horses, reindeer, boars, ibex, and other mammals I canÔÇÖt identify. Stunned, ecstatic, I felt like I almost blacked out. Some animals were walking; others ran or galloped. Every gait was distinct. Some of these animals seemed to hunt, others were hunted. I think I saw a salmon with a perfectly defined dorsal fin; and nearby, possibly a vertical pig, drawn this way because the wall formation suggested it. I perceived a grouping of animals gathering to drink, rest, eat, play. Every image felt palpable, somatic, sensually rendered, real.

The idea that perspective was invented in Florence in 1414 collapsed in an instant. Here, larger mammals are in front of smaller ones who trail behind; animals at the back of packs are smaller than those in front. ThereÔÇÖs also whatÔÇÖs called reverse perspective, the sort of system used in China, where closer things are rendered smaller than farther things. Elsewhere, an ibex is depicted from behind and over the shoulder ÔÇö an incredibly sophisticated perspective. One horse is seen from a highly accomplished three-quarters view. Imagery seemed adjusted for curvatures and protrusions of the walls in the same ways that Renaissance frescoes adjust for distortions, distance, and odd viewing angles. I saw a bison with one horn curving up, the other curving down ÔÇö either from battle or birth. Whatever the cause, this was something that had been seen and intentionally rendered. A reindeer evinced shaggy pelage on antlers. Males appeared to sniff females for signs of estrous; others tilted horns, stomped the ground, charged forward, or assumed postures of sexual submission. In one gripping image, I thought I saw a wolf jumping up and bringing down a horse by the neck ÔÇö the horseÔÇÖs tail is raised in the exact way they hold their tails when alarmed. Nearby, a bison has three spears in its side. Regardless of whether this and other images depicted hunts or were instructions for how to approach and bring down bison, these painters loved depicting action, movement, gestures, things happening at very particular times. Nothing seemed only imagined; everything felt observed, studied, thought about, recorded. The psychovisual acuity for and empirical science of animal behavior boggled.

So does the desire for color, which came from roots, berries, bark, minerals, clay, red and yellow ochre, and minerals like hematite and manganese oxide, and were mixed with viscera, water, sap, soot, and blood. Moreover, these substances had to be gathered and transported; every color evinces desire for something more than just graphic outlines. Yet their lines are long, confident, fluid, and drawn from the sort of charcoal sticks youÔÇÖd find in any fire. The shading I saw on the rear hoof and fetlock of a bison, the first thing that I set eyes on when our guide shined her light in the gallery, never leaves me. It is the punctum ÔÇö the flash point ÔÇö of the caves for me. As are long, wavy red strokes that looked familiar. When I got home I made a studio visit, and I suddenly remembered where IÔÇÖd seen these lines: on studio walls made by artists dragging paint-covered brushes, fingers, or sticks to empty brushes of pigment, test colors, or just make marks.

For me, all this gave the lie to our long-held, egocentric idea that cave paintings are the mystic machinations of master shamans who are portraying some primitive spirit or dream world. Instead, I saw an astonishing artistic naturalism, a stylized realism that accounted for every individual body part, action, dorsal line, and body language, down to what season or even time of day these images were made (bison chewing their cuds come midday, et cetera). I venture that when it comes to the best of these paintings, mammals have never been rendered better in the history of our species. These are the paintings of people who looked at mammals for over 30,000 years ÔÇö far longer than all of recorded history combined. I was seeing visual wisdom, the hard work of looking and taking the time and trouble to make exact renditions of what one watched. Looking at these images, I began to know things we donÔÇÖt know anymore but still know in our bones. I felt the narcotic power of this naturalism, what Norman Bryson has called ÔÇ£the metaphysics of presence.ÔÇØ I gleaned the carnal pleasures of painting textures, surfaces, and fur in variable viscosities; the vision of a world unfolding yet held in exactly these moments, and not framed by drawn lines but within geology. I felt a nobility of subject matter and process.

These astounding levels of visual intelligence tell me that had these people wanted to make only symbolic images of their mysticism and magic, they could have. One author of a typically romantic book on cave paintings plaintively writes, ÔÇ£We do not know what the images meant to those who made and viewed them.ÔÇØ The clap of thunder that sounded for me in the caves was that the world outside and around these people was the same as the world that was inside them. Among the chief subjects of these paintings is the inscribing body of the painters, and the pleasures taken in making these paintings. To turn this gigantic worldview into an either/or proposition ÔÇö into demeaning all this as merely hunting magic and dream worlds on the one hand, or going just as far in the other direction, lauding everything here as the masterpieces of a mysterious people, feels false, limiting, more Romanizing of the world in one easy way or another.

ItÔÇÖs estimated that about 99.9995 percent of all Paleolithic art is lost to time. My sparse research suggests that weÔÇÖve discovered about 400 painted cave sites, and almost that many open-air sites with art. ThereÔÇÖs evidence our ancestors didnÔÇÖt just paint rocks, that they drew in vertical riverbanks, in soft mud, sand, slurries of calcite that coat limestone surfaces; that they engaged in woodworking, body decoration, bark painting, the making of clothing, skin sewing, stone carving, firing clay, carving bone, and the like.

I conjecture that art in caves was, by far, the exception rather than the rule. Enormous, now-extinct cave bears, moreover, would have made cave-dwelling incredibly risky, if not suicidal. The preservation of cave paintings occurs only under incredibly narrow and lucky circumstances: There must be a very small temperature range (a steady 53.6 degrees Fahrenheit) with no freezing or thawing in 30,000 years, no wind bombardment, plant growth, water inundation, erosion, earthquakes, solar rays, human destruction, and on and on. The first person who stumbled on the Niaux caves in 1600 instantly inscribed his name and the date next to an ibex.

I saw absolute masterpieces of animal portraiture at Niaux, among the greatest paintings IÔÇÖve ever viewed. However, I also saw images that were crude, clownish, the scrawls of kids, and maybe even┬ádoodles. Indeed, it would be impossible that everything painted here and for thousands of years would be a ÔÇ£masterpiece.ÔÇØ┬áThe good and bad, however, all evinced things we can instantly relate to as zoological, psychological, frightening, funny, or just fun. I didnÔÇÖt notice any of the famous handprints made by spitting colored pulp around oneÔÇÖs hand. Recent computer studies of these handprints, however, suggest that about half of them are womenÔÇÖs. (Bye-bye, male-artist myth.) I saw some of the dotting and dashes that many conjecture are celestial observations or calendar notations, but I didnÔÇÖt spy any of the many vulvas and phalluses found at other sites ÔÇö the kinds of things kids were drawing then, what kids have always drawn when left alone. Either way, this is by and large the art of a young people, as life expectancy is thought to have been 35 years for men and 30 years for women.

Still, my romantic self ached for whatÔÇÖs not here. There are no images of war. Perhaps it didnÔÇÖt exist yet, or nomadic groups of 50 to 100 people had no need to have war. Given how much these people loved depicting action, I think that theyÔÇÖd have rendered war if it had existed. There are no dogs because dogs didnÔÇÖt exist yet. But why no pictures of the sun or moon, mountains, trees, or fire? Or tools? Why no fruit, insects, lakes, or rivers? No snow or rain? There are depictions of sex (not in Niaux) but, alas, no human portraiture. These are the proclaiming shadows cast by cave art for me.

In Niaux, art got much bigger for me, and became the flying buttress for all the art that follows it, maybe for much that is human. I donÔÇÖt want to sound like an insane art-critic version of Werner Herzog rhapsodizing about ÔÇ£albino alligators.ÔÇØ All I know is that something seismic hit me in those caves, some capacious cognizance, cryptic, wakeful. Whatever it was, a new type of human existence entered my consciousness ÔÇö one that I now recognize as, at once, my own and collective.

Note: The best book on cave paintings and only one that avoids the mystic mumbo-jumbo projection of other books is R. Dale GuthrieÔÇÖs The Nature of Paleolithic Art.