The revelations in Alex Gibney’s new documentary Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief won’t come as a huge surprise to anyone who’s read Lawrence Wright’s devastating, similarly titled book-length exposé. But a movie is a very different thing than a book, for better and for worse. There were numerous books about SeaWorld’s shady practices before Blackfish came around; there was tons of literature on climate change before An Inconvenient Truth came out. Raise your profile and you raise your stakes. This is something Gibney and Wright understand. It’s also something Scientology understands. That’s probably why they’ve been fighting back so vehemently against this film, which is opening in limited theatrical release this week and will show on HBO later this month. (It premiered at Sundance in January, with a heavily buzzed-about screening that saw festival volunteers forming a human chain around Gibney and his subjects afterward.)

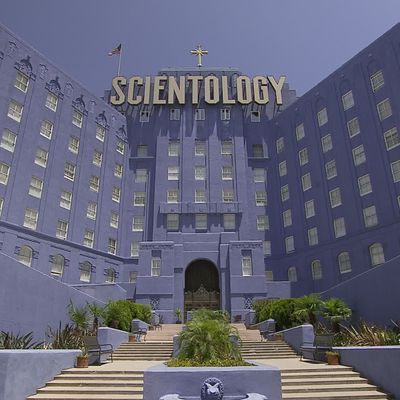

The cult is right to be scared. Going Clear is spectacular stuff. Literally. Scientology thrives on spectacle, and one big advantage the film has over the book is that it can show us footage of Scientology’s big “events,” which look like Nazi rallies crossed with Hollywood awards shows. It can also show us video footage of the church’s leaders dissembling and evading when confronted by reporters. Seeing is disbelieving: Watching this stuff, instead of merely reading about it, somehow makes Scientology both more ridiculous and more chilling.

The film starts, much like the book does, with writer-director and longtime Scientology adherent Paul Haggis discussing how he was drawn to the cult in the early 1970s. At the time, he was a lost, lovesick young man and aspiring filmmaker looking for meaning and entertaining a healthy sense of curiosity. Much of the first section of the film, however, discusses Scientology founder and sci-fi novelist L. Ron Hubbard’s rather nutty life and career, as well as the ways in which so much of Scientology’s belief system reflects aspects of the sci-fi genre — stuff that makes for entertaining, imaginative worlds as fiction, but sounds crazy when presented as fact.

Several of Gibney’s interview subjects were at the topmost levels of Scientology — including Marty Rathbun, who was essentially the church’s second-in-command and chief enforcer for many years — and they offer insights into how Scientology actively pursues celebrities, and the tactics by which it keeps them bound. Among these celebs, of course, are the church’s two supposed crown jewels, Tom Cruise and John Travolta. Travolta, it’s suggested, is kept in the group because they have mountains and mountains of dirt on him, the result of years of spiritual “auditing” (the process by which Scientologists basically reveal their deepest secrets, which are then catalogued and brought out whenever someone needs some, uh, encouragement, as the Mafia likes to say). In Cruise’s case, he had actually put some distance between himself and Scientology in the 1990s, but the group insinuated itself back into his good graces by working overtime to wreck his marriage to Nicole Kidman, who had always been skeptical about them.

Why do people even get wrapped up in such a crazy cult? As the film makes clear, Scientology presents itself initially as a set of tools to help you live a better, freer, more purposeful life. Unlike other religions, it doesn’t actually tell you what its core belief system is until you’ve spent years and years (and, most likely, thousands and thousands of dollars) as a member. It’s only when you ascend “The Bridge” and get to that Operating Thetan level that you’re given the sacred text — L. Ron Hubbard’s handwritten notes explaining humanity’s crazy backstory, about how Earth is a slave planet and how humans were brought here billions of years ago by the intergalactic dictator Xenu, placed in volcanoes, and blown up with hydrogen bombs, etc. (When he finally read Hubbard’s notes, Haggis says he thought, “Maybe it’s an insanity test? Maybe if you believe this, they kick you out?” No such luck.)

It’d be funny if it weren’t so tragic — and possibly even criminal. As Going Clear posits, for all the crazy mumbo jumbo, Scientology is also a brutal, heavily retaliatory organization. Its current leader, David Miscavige, who took over after L. Ron Hubbard’s death, sticks to the founder’s credo, “Never defend, always attack.” The brave souls who spoke out for Wright and for Gibney, some of whom were at the uppermost levels of the organization, have been harassed, followed, threatened. But many of those still in the religion fare worse, with elaborate punishments that would be considered assault and torture if you or I did it, but in Scientology’s case are — amazingly — protected under the First Amendment as freedom of religion. The thinking apparently goes like this: Someone who’s been brainwashed claims they were a willing participant in their punishment; examples from other religions, such as monks who take vows of silence or give up their belongings or flagellate themselves, give Scientology additional cover. It’s also worth noting that the group spent decades trying to get the IRS to classify it as a religious group, and finally managed to get it done in part by launching a vast number of countersuits, then promising to pull them in return for religious-group designation. (Going Clear makes it clear that, had Scientology not gotten this designation, it probably would have gone bankrupt.)

If Gibney’s film sometimes seems a little shapeless, that’s understandable: There’s a lot of stuff in Going Clear, and it doesn’t lend itself easily to a feature-length structure. The salacious celebrity stuff has to live alongside the sad tales of lesser-known individual members who had their families torn apart; the heavily modernized, fascistic recent iteration of the group has to live alongside Hubbard’s own kooky antics; the legal intricacies of Scientology’s defense have to live alongside the dramatic tales of surveillance. Gibney’s a bit like a kid in an exposé candy store here, and you can sense him trying to cram as much as he can into the film. Good for him: Going Clear is jaw-dropping. You wouldn’t really want it any other way.

A version of this review ran on January 25 after Going Clear’s Sundance premiere.