Would you like to see a two-hander in which Jake Gyllenhaal plays a hunky but bashful British beekeeper, hemming and half-smiling, while Ruth Wilson, so recently embaubled with a Golden Globe for The Affair, plays a charmingly ditzy astrophysicist? Would you like to watch the pair meet cute at a barbecue, grope their way toward romance, survive infidelity, and face tragedy together? I would; it sounds like an engaging play. Unfortunately it’s not the one now running at the Manhattan Theatre Club under the title Constellations, even though all those things do happen in it. But since Nick Payne, the author, is unwilling to give us that romantic trifle, this delightful, beautifully acted, and infuriating new drama is so much more, and less.

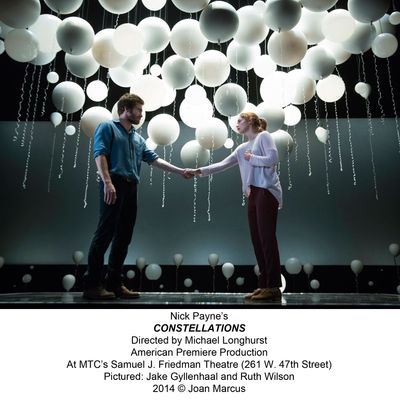

The more and the less both stem from the gimmick with which Payne attempts to lift the material to an intellectual plane. We can at once guess that that’s the goal from Tom Scutt’s chic set design, which looks like a birthday party on Alpha Centauri, with armies of glowing white balloons floating above a raised white platform. But what do the Busby Berkeley–meets–Voyager décor, and the interstellar music, refer to specifically? Happily, Wilson’s astrophysicist character, Marianne, explains it to us as she explains it to Gyllenhaal’s character, Roland:

MARIANNE: Despite our best efforts, there are certain microscopic observations that just cannot be predicted absolutely. Now, potentially, one way of explaining this is to draw the conclusion that, at any given moment, several outcomes can co-exist simultaneously.

ROLAND: This is genuinely turning me on, you do realize that.

MARIANNE: In the Quantum Multiverse, every choice, every decision you’ve ever and never made exists in an unimaginably vast ensemble of parallel universes.

That’s what Payne tries to give us: a play about every possible way the story of Marianne and Roland could spool out in the multiverse. This can’t really be represented onstage, of course; you can barely get two stories going at once in the theater, let alone innumerable billions. What Payne does instead is show us sequential snippets of selected variants. (It’s hard to count, but I’d guess there are a dozen permutations of a few basic choices cycling through the play.) The couple, for instance, meets three different ways at the barbecue. Who is unfaithful, and how much, and with whom, is presented in four different variations. At least three times the tragic element appears to end tragically; one time it does not. In any case, we only see one option at a time, so the intended multiplicity isn’t really achieved. To cover for this, Payne tosses in another dramaturgical trick, this one more familiar: The sequence within the stories is jumbled, with bits of later developments sometimes spliced into early scenes to tease and confuse. If you like sudoku, you’ll love this.

I happen to find puzzling out such things enjoyable; your mileage may vary. Either way, there are several dramatic problems that arise from Payne’s putting his one egg in so many baskets. The biggest is that not every possible alternative within a supposed multiverse is meaningful. When Marianne develops a brain tumor, there are really just two results to be played out; if it’s benign one time, it’ll be malignant another. Marriage, too, is a yes-or-no proposition. So you generally know what options are coming next. And since Payne doesn’t really follow those options for very long, we never get a strong feeling of consequence; the meaning of the multiverse theory within actual human life is left undramatized. The musical If/Then, which embraced a similar concept, made the more manageable choice of focusing on the permutations arising from just one branching of the multiverse and could make a coherent case about the implications (or irrelevance) of choice. Constellations rarely gives us the chance to explore ideas like that, though when it briefly does, it’s very moving. “We have all the time we’ve always had,” Marianne tells Roland. “You’ll still have all our time. … There’s not going to be any more or less of it.”

For the most part, though, the multiverse superstructure turns out to be inexpressive and so overbearing that it sucks the dramatic nutrition out of the play. That the stories it is meant to support do not in fact wither or get crushed beneath it, and remain quite engaging, is a tribute to Payne’s highly playable dialogue and the immense skill of both actors. Wilson’s Marianne is the more baroque invention, given the brunt of the playwright’s justifications, but she folds that into a canny take on an instantly recognizable type of woman, constantly second-guessing what she says but never what she believes. And Gyllenhaal is terrific (as he was in Payne’s If There Is I Haven’t Found It Yet, which played off Broadway in 2012) adapting his subtle movie technique to the more presentational requirements of the stage. (He easily makes lines like “Yeah, no, yeah, I am, yeah,” not just naturalistic but emotionally legible.) Together, and most astonishingly, the two make the play’s innumerable leaps (which replace a normal play’s transitions) in brilliant lockstep, like synchronized divers. Sometimes those leaps happen every few seconds, which however funny it is to watch must be devilish to perform, especially when the mood shifts radically. One bit starts with Roland nearly in tears.

But it does get wearing, even at just 70 minutes. (The director Michael Longhurst moves it along as fast as he can.) And when Payne permits the actors a scene that lasts more than a beat, you realize what you’ve been missing, because it is only then that you start to get gripped. At those moments, you may find yourself asking why a playwright would so willfully abjure the stuff of drama when he’s clearly so capable of providing it. I guess in some other universe he doesn’t.

Constellations is at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre through March 15.