Two and a Half Men aired its very first episode on September 22, 2003, nestled between long-gone CBS hits Everybody Loves Raymond and CSI: Miami. Viewers immediately took an interest in the Odd Couple–esque comedy starring Charlie Sheen and Jon Cryer: An Eye press release at the time touted the fact that Men was the most-watched new show of premiere week and had retained a bigger percentage of its Raymond lead-in than any other comedy the network had put behind it in the 9:30 p.m. Monday slot. Twelve seasons, 260 episodes, two major cast changes, and one epic talent meltdown later, Men will finally shuffle off the prime-time coil this night as one of the most financially successful sitcoms of the century to date.

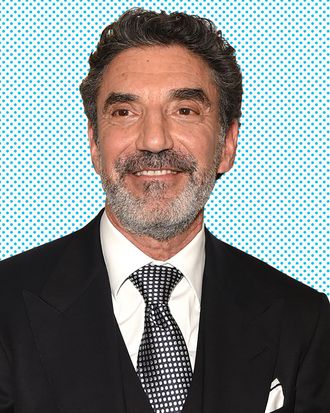

Its longevity is all the more impressive given Sheen’s stormy departure at the end of season eight: A show that could’ve easily crumbled instead found a new co-lead (Ashton Kutcher), rebooted huge parts of its premise, and prospered for another four years. And while its current audience of just over 11 million viewers is notably smaller than at the show’s peak, Men still ranks among the top five most-watched sitcoms on TV. Vulture caught up with series co-creator Chuck Lorre by phone last week, grabbing him for 20 minutes as he drove to work producing two of the small screen’s other five most-watched comedies (The Big Bang Theory and Mom). He told us how he and his production team kept Men alive after Hurricane Charlie, what we can expect from the finale, and his response — in Yiddish! — to those who won’t at all be sad to see the show go.

So now that Two and Half Men is headed off to the TV afterlife, what do you hope its legacy will be?

I don’t get to write the legacy, do I? Other people will opine as to what the show’s legacy is, or if there is one. To me, it’s a show that, like Roger Maris’s 61 home runs — it has an asterisk next to it. It really was two shows. It was a series that, oddly, ended twice for me. I watched it implode, and I was certain it was over. And then we just wrapped it once again, Friday night. So it’s a very strange experience for me because in a way it’s become two shows, not one.

Let’s talk about that feat, of keeping the show going after losing your star. Were you always confident you could do what you ended up doing?

When [Kutcher] and Jon Cryer walked onstage at Carnegie Hall to announce that the show would return, I remember siting in the audience, thinking, I have no idea how we’re going to do this. Our original intent was to [make Sheen’s replacement] a darker, more decadent character. But after spending a few hours with Ashton, I thought, No, that’s not this guy’s energy. He’s so much more life-affirming. He looks out at the world, and he’s excited about it. When I first met him, all he wanted to do was talk about the purchase of Skype by Microsoft. He was so invested in the technological landscape. And I wanted to bring that into the show. It changed the dynamic immediately. The conversation about his character initially was, we were going to have him be a ne’er-do-well, with a dark, nefarious lifestyle — and we threw that out. Ashton embodies something so much more “up,” so we rebuilt the show around him being an internet millionaire who’s excited about life, who’s excited about what he does — and yet is completely incompetent at maintaining a relationship with women. The alpha dog on the show was no longer a predator. If anything, he was something of a victim in relationships, sort of bumbling.

That was a pretty big shift from how Men had worked its first eight seasons.

That was a big change. The series had flourished with the charming playboy character that Charlie embodied. It was a great character to write for. And Charlie had this amazing Teflon ability that allowed the audience to forgive him his excesses. It’s a rare ability. Dean Martin had it — he could do anything in that day and age, along the same lines, and it was okay.

When you were thinking of how to approach the transition, were you inspired by any previous sitcom-star shuffles?

Well. [Pauses.] When they replaced Coach on Cheers, after [Nicholas Colasanto] passed away, they brought in Woody Harrelson. And he played a younger version of the same guy — impenetrably and wonderfully and charmingly stupid. And he was brilliant at it. It was a perfect transition during a very difficult time for that show. The show was early in its run, they lost one of their key guys — and they made the transition work by keeping the character; the guy behind the bar was a lovable knucklehead. That worked. And we were all aware of that.

But I was kind of burned out, personally, by all the tumultuous stuff that went on. I didn’t want to do a series anymore about a character who was imploding, who was [running through] women and alcohol. I was really exhausted by that whole experience. I wanted a chance to move the show in a lighter direction, and Ashton provided that opportunity. I loved the eight and a half years that we did with Charlie. I loved the character that he created, and he played it beautifully. Perfectly. He made it look very, very easy. But I was done with it.

So we tried to design a character that captured what was special about Ashton. And that was a lot of fun. It was a stumbling process. I don’t think we got it right, right out of the gate. We didn’t quite understand what we were doing as we were doing it. But we looked at each other and said, “Why not try?” There’s no harm in trying to rebuild the show instead of walking away. Ashton’s chemistry with Jon became immediate. They had a good time working with each other. And the idea of keeping the show going became very realistic, very quickly.

Cheers had other big transitions, which were more like what you did with Men. After Shelley Long left …

Kirstie Alley brought in a whole new sensibility. You’re right. And it worked great, and it added life to that show. And this added life to our show. It opened up so many opportunities that we would have never imagined. So in that tragic transition, we were given the opportunity to write lots more stories about different things. And maybe that’s what helped us keep going.

And now here you are at the end of Men. Guiding a series in for a landing, particularly one that has been on as long as this, is always a challenge. What was the thinking as you and the other writers of the episode (Lee Aronsohn, Don Reo, and Jim Patterson) plotted out the hour?

The show has become something other than a TV show because of all of the drama surrounding it. So I thought we needed to address the characters in the show — the fictional nature of the show — and the macro elements, the tabloid elements that have become attached to [it]. When you say Two and a Half Men to anybody now, their eyebrows immediately go up. And they want to talk some trash! That’s part of our legacy. So I thought, let’s go for it. Let’s do a finale that addresses all of that, that doesn’t ignore that the show has a miasmic cloud around it. Before we started writing the finale, I said to everyone, “We never really had any dignity attached to the show. There’s no reason to start now. Let’s try to put on an hour that’s big and brash and vivacious and pisses some people off.” Hopefully it’s funny. Doing one of these shows as an hour is an entirely different structure.

I know you won’t talk about whether Charlie Sheen returns, though the title of the episode (“Of Course He’s Dead”) indicates his character will be part of the proceedings. But what specifics can you offer?

There is something of a mystery that drives the plot. I think from the very first scene, you’ll see where we’re going. I don’t want to say much more than that. I can’t speak to whether people will like it or not, because that’s none of my business. But I loved doing it. It was so much fun.

This is admittedly a bit of a boilerplate question, but it seems appropriate in a conversation about an ending: Is there a particular episode of Men that stands as your favorite?

That’s really hard. It’d be really hard to pull one episode out. We got 262 shots at making a TV show over 12 years. There are an awful lot of moments where we achieved what we set out what we set to do.

Last year, some media outlets published stories online with headlines saying you had “apologized” for Two and a Half Men at an awards show. But you really didn’t.

That was a joke! We’d gotten this award for Mom for depiction of alcoholism. And it’s clearly 180 degrees from what I’d been doing all those years. And so it was an off-the-cuff remark. I thought it was funny. I was surprised that it got reported as a legitimate headline. I worked really hard on [Two and a Half Men]. Why would I apologize? There are things I have to apologize for — it just doesn’t happen to be a TV show.

And yet while there are literally millions of fans of Two and a Half Men, the show has also generated more than its share of criticism — not just people who don’t think it’s funny, but some who think the characters are just awful, in some cases, misogynistic people. When you heard or read such complaints, how do you respond?

How do I respond? Change the channel. It’s a miracle to get a show on the air. It’s a miracle to keep it on the air. Let me tell you a story about my aunt Mickey. She passed away a few years ago. She was in her late 80s when Two and a Half Men was going strong. And she used to call me every day after the show aired. She’d go, “Chuckie, last night’s show was very blue.” And I’d say, “Was it too much? Should we pull it back?” And she’d say, “No! More.” She loved it. And she, for me, was a touchstone for what we were doing. She got that we were being mischievous and that we were being the bad-boy TV show. The fact that she was sitting there in Ft. Lauderdale watching it meant a lot to me.

It’s preposterous to think everyone is gonna like what you do. That’s a recipe for insanity — to hope that everyone is gonna like what you do. And the show found a voice early on, and it was somewhat provocative. But the goal was not … to outrage and incense. It was to create laughter. And for some people, it worked. And for some people, it didn’t. As my people say, Gai gezunterhait. Go with God.