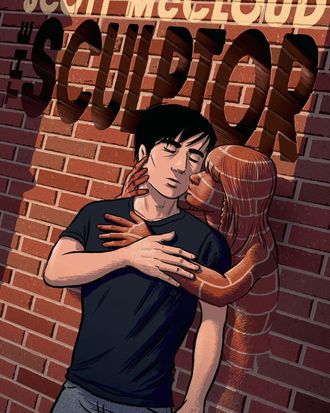

Ever since the 1993 release of his Understanding Comics, and his subsequent books Reinventing Comics and Making Comics, Scott McCloud has been universally acknowledged as one of the comic worldÔÇÖs foremost theorists. Not a bad thing to be, but also a slightly misleading one ÔÇö long before he made his name explaining how comics work, McCloud, 54, was himself an award-winning comic artist. With The Sculptor, his hefty first foray into graphic novels, McCloud has dispelled any questions about where his true talent lies. Recently optioned by Sony Pictures, The Sculptor ÔÇö the story of David, an ambitious young artist struggling to realize his gifts ÔÇö is gorgeous, moving, wry, and wise.

McCloud spoke on the phone about his graphic novel, comicsÔÇÖ cultural ascendance, and marrying a Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

YouÔÇÖre known as someone whoÔÇÖs fluent in the structure and function of comics. Did you feel with The Sculptor┬áthat you had to make a graphic novel that would stand up to the sort of extremely close reading that youÔÇÖre known for doing yourself? Was Scott McCloud the theorist watching over the back of Scott McCloud the artist?

Yeah, I felt tremendous pressure. I would have felt pressure just based on Understanding Comics, which I wrote trying to be nothing more than a good reader. But I also had the temerity to write Making Comics, so it was even worse! So there was pressure. For whatever reason, though ÔÇö I guess I just have that sort of temperament ÔÇö I just took the pressure as rocket fuel, as a kind of message from my readers that failure was not an option. A real belly flop wouldÔÇÖve been just too humiliating and conspicuous.

YouÔÇÖd sort of put up a flag and said you know what makes a good comic.

Right. With the books IÔÇÖd written, I was basically saying, ÔÇ£Hey, everybody look!ÔÇØ as I either succeeded or failed. So I had to do my best to succeed. ThatÔÇÖs really all we can ask from ourselves, to know that we did the best we could with what we had. ThatÔÇÖs sort of how I feel about this one: that itÔÇÖs the best I could put down on the page at this time in my life.

One of The SculptorÔÇÖs biggest questions, and one that David doesnÔÇÖt necessarily find an answer to, is what makes a well-lived life, and what lengths one should go to in order to achieve that. Did you feel like you had a handle on what you wanted to say about those questions before you started work on the book? Or did you arrive at your conclusions by doing the work?

The ideas that are at the heart of the story really only came into focus for me in the process of writing and rewriting and rewriting. It was a gradual shift away from the story that the young me wanted to tell ÔÇö because this was a story that I conceived of when I was half my current age. As I worked, I shifted gradually toward the story that the older me knew how to tell: a story of acceptance, of the relentlessness of time and decay, of the futility of art. These are not the sorts of things that a 20-year-old usually embarks on. To be able to engage with those things in a way that still celebrates them and finds them beautiful was the way I was able to honor the vitality of the younger manÔÇÖs story.

DavidÔÇÖs love interest is Meg, who fits right into the trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. YouÔÇÖre obviously aware of that character as a maybe overused archetype. Why did you go down that path with her?

I was definitely aware of the concern with what Nathan Rabin has identified as the more toxic aspects of the trope. The trope got a bit out of control and became a kind of literary witch hunt after a while, something that I think Nathan was concerned with. When he walked it back a little later on, a lot of really terrific and very, very different characters started to get thrown into that same pond. But nevertheless, I certainly took a very close look at the character. The reason I couldnÔÇÖt steer her away from that collision course entirely is because Meg was based so closely on my wife. I married the trope ÔÇö what am I gonna do?

ÔÇ£I married a tropeÔÇØ sounds like a postmodern ÔÇÿ50s horror movie.

I mean, look, you know there really are people a lot like that. TheyÔÇÖre not all fictional. And interestingly enough, my wife, Ivy, had a fondness for some of those very same characters that were being pilloried. I had to give some thought to the nontoxic aspects of that archetype. I donÔÇÖt think itÔÇÖs an entirely regressive spirit thatÔÇÖs inhabiting characters from time to time. In fact, I think often it has an empowering, progressive impulse. Usually the Manic Pixie Dream Girl is a reasonably empowered character whoÔÇÖs pretty much in charge of the story, who is usually a kind of Dionysian counterbalance to an Apollonian dullard ÔÇö which my hero, David, kind of is.

ItÔÇÖs also interesting which archetypes people choose to see as being tired and which ones people think are still fresh. David is a man whose power becomes both a gift and a curse, which is a problem he has in common with a million comic-book characters. But people donÔÇÖt seem to feel like that archetype is regressive, even though itÔÇÖs been done to death.

The whole business of archetypes generally  I see literature as on a continuum, all the way from Alice Munro on one end to Little Red Riding Hood on the other. I thought it was okay to place The Sculptor somewhere along that continuum. Sometimes people seem to think that only one end of the scale is the correct one. You also touched on something else that I think is really important: Archetypes traditionally associated with male genres seem to get a pass, and I found [that] especially concerning. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl is an archetype that shows up in romance almost exclusively, and our reaction is to mark it for death. We shouldnt kill what we dont understand. Theres a reason why this character shows up again and again. I dont know how well a job Ive done of investigating those reasons, but I hope theres something in The Sculptor that makes Meg worthwhile.

With the rise of superhero movies, comics are driving pop culture in a way that we havenÔÇÖt seen before. On the one end itÔÇÖs easy to see this period as a golden age for comics. But do you feel like the explosion of interest in comic-book characters has also made people more interested in meaty graphic novels like The Sculptor? Or are these things existing on entirely different planes?

ThereÔÇÖs some spillover. Anecdotally youÔÇÖll see cases where people understand that a movie or TV show is the ancillary product of a singular work, like Watchmen, and have a sense that it was something worthwhile as a comic. I think people are less likely to go to a comic if they just see itÔÇÖs a part of a corporate series of products, like with The Avengers, for example. Although I canÔÇÖt say exactly how well those books sell; IÔÇÖm sure they sell relatively well. But the real stunning spillover is, like I said, in things like Watchmen, which probably sold a million copies before the movie even came out, just because of that awesome trailer with the Smashing Pumpkins song.

That sort of ambient interest in comics canÔÇÖt be anything but helpful, can it?

The generalized buzz around nerd culture hasnÔÇÖt really been bad ÔÇö itÔÇÖs probably helped us somewhat. ItÔÇÖs kind of charged the air a little bit so that works associated with our genre ÔÇö medium, I should say medium ÔÇö are a little bit more likely to get a fair hearing. And somehow, despite the prevalence of the superhero genre that sells on TV, people do seem to be getting the message that comics are about more than just superheroes. That seems to be an article of faith on the part of a lot of folks ÔÇö maybe not a majority of them. IÔÇÖm sure there are a lot of people who think that comics are just superheroes. But I think there are more people than ever who understand that the medium itself is just a blank page, and itÔÇÖs capable of accommodating any level of ambition, or creativity, or literary intent.