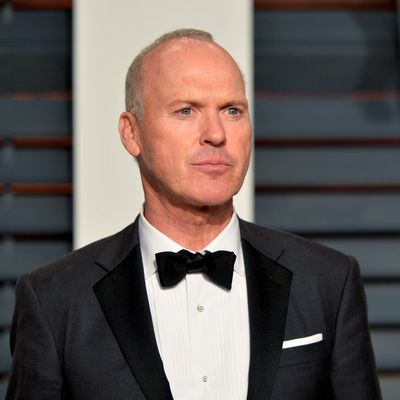

Who doesn’t love a comeback story? Well, the Oscars, apparently. Don’t get me wrong — they seem to like a comeback story. They can get behind a comeback, sort of — up to a point. But every great comeback tale seems to falter at the finish line — and maybe none more so than the improbable rebirth of Michael Keaton in Birdman.

You may not think Keaton deserved to win (in which case: Congrats! He didn’t), but no one can deny that (a) his personal narrative is a comeback tale perfectly suited for a show like the Oscars, and (b) it’s a little weird that his movie, Birdman, was celebrated for almost everything but the tour de force performance at its center. If you don’t buy Keaton as Riggan Thomson, the aging onetime superstar trying to reclaim some measure of artistic respectability, then you likely won’t buy the whole film. But it’s really hard to imagine how you buy the whole film — Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Original Screenplay, Best Picture — but not Keaton’s performance.

Yet Keaton’s loss is not that surprising given Oscar’s history. Of all the common wisdom parroted about the Oscars, the idea that the Academy loves a comeback story might be the most fallacious. There have been plenty of intriguing comebacks surrounding the Oscars, but they rarely deliver. Mickey Rourke, exhumed from the dead and nominated for Best Actor for The Wrestler, lost in the end to Sean Penn. In 1995, John Travolta — who turned up last night in an off-putting appearance that played off last year’s off-putting appearance — offered a prototypical heartwarming tale with his work in Pulp Fiction; even the studio fought Tarantino about casting Travolta in the movie, and then he went on to earn a Best Actor nomination, 17 years after his first nomination for Saturday Night Fever. Welcome back, John Travolta — er, not so fast. He lost in the end to Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump. (Hanks, of course, had come all the way back from winning Best Actor the year before for Philadelphia.) Annette Bening won a Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy for The Kids Are All Right, but lost the Oscar to Natalie Portman. Colin Farrell won a comeback-of-sorts Golden Globe for In Bruges, and he didn’t even make it into the five nominees for the Academy Award. Matthew McConaughey seemed to complete a comeback last year with his Best Actor win, but he’s a different case than Keaton or Rourke: McConaughey reinvented himself, yes, but it’s not like he disappeared for years; and by the time he won the Oscar, his comeback, which started with Bernie and Killer Joe, was already two years old. In fact, the far better comeback story was Bruce Dern’s, one of the actors McConaughey beat.

I guess you could point to Ben Affleck’s Best Picture win for Argo as the most dramatic recent Oscar comeback story that actually came all the way back, except Affleck wasn’t even nominated for Best Director, and what, exactly, was he coming back from? The ignominy of Bennifer? His tale was surely heartening in a dating–Jennifer Lopez–will-only-temporarily-derail-your-career kind of way, but it wasn’t nearly so linear or visceral as Keaton’s story: the onetime superstar, known for a superhero franchise, who’d fallen off the map for more than a decade only to return basically playing himself.

You might also argue that the point of the Oscars is to honor excellence, not to deliver heartening narratives, but come on. Much had been made of Selma being undernominated in a year that marks the 50th anniversary of the historic events the film portrays. And over and over again during the telecast, there was a palpable sense of a huge missed opportunity — the stirring night that could have been. (Instead, the Oscars chose to shamelessly and transparently court younger viewers with a long anniversary celebration of The Sound of Music.) Keaton’s comeback wouldn’t have carried quite the same resonance, but it’s yet another example of how, often, in a town that’s supposedly built on delivering rousing narratives, the story consistently falls apart in the very last act.