It was a misunderstanding — almost a clerical error — the way the gifted Compton rapper Kendrick Lamar got to be famous in the first place: He made a very incisive song about inner-city alcoholism that a lot of people mistook for a party anthem. It was called “Swimming Pools (Drank),” and I saw him play it the first time I was sent to cover his live show, at an absurdly lavish party thrown in the lobby of a planetarium to celebrate the cosmically named new scent of a popular-selling body spray. Lamar’s set was short and, presumably, generously compensated. While he played, people in rented astronaut suits traversed the floor with trays of Champagne; a rumor circulated that the company was raffling off a trip to space. These are the kinds of scenes some aspiring rappers dream of inhabiting, but Kendrick Lamar has never been that kind of rapper. He doesn’t even consider himself a rapper, really; he told Stephen Colbert in an interview late last year that he prefers the term writer. And like many who claim that particular mantle, Lamar often wears a spacey, inwardly focused expression and oscillates between a vibe of jumpy anxiety and near-monastic calm. That was definitely what he projected that night at the planetarium; as people lifted their glasses to the repeated word “DRANK,” Lamar seemed a little puzzled and radiated this sense that he did not really know what to do with himself now that he was a superstar. “Like Barack Obama,” a Billboard writer remarked a little while later, in a recent cover story, “Lamar is an introvert with an extrovert’s job.”

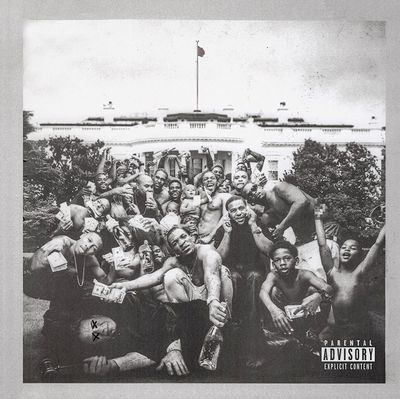

But judging by his staggering and incendiary sophomore album, To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar is done conforming to anybody else’s job description. It is a work of focused intensity — one of the most incisive and imperatively timed records about race in recent musical memory. You can tell that Lamar does not consider it a pop record so much as a work of revisionist American history: It begins with a sample of Boris Gardiner’s dreamy and uplifting soul curio “Every Nigger is a Star,” and its finale is a spoken-word torrent reminding us of the N-word’s etymological roots as a synonym for royalty. “Why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street?” Lamar raps on the spitfire single “The Blacker the Berry,” which is not a call to arms so much as an urgent and scathing exploration of the artist’s self-perceived hypocrisy. Though it addresses recent American unrest, To Pimp a Butterfly is something more complex than a rallying cry; it is a depiction of the internal struggle to believe in anything deeply enough to shout it. Deftly weaving together dual narratives of Lamar’s distrust of fame and his country’s historical distrust of black people, Butterfly is as much about the war on the streets as it is the war within.

Lamar’s signature trick is to deliver a verse — like the scene-stealer he spit while guesting with alt-rock Stomp production Imagine Dragons at the 2014 Grammys — that gradually builds in intensity, beginning as a soft-spoken Jekyll and ending a wild-eyed Hyde. Or maybe beginning as Method Man and ending as ODB. Lamar crafts different flows and personae for the many voices in his head, and on Butterfly, there are enough of them to sound like an entire (one-man) rap crew. (“Kendrick, this is your conscience,” an alien voice beamed down in “Swimming Pools,” in a flow now so iconic, it’s since been imitated by the likes of Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé.) This multiplicity of persona is used to great — but often anxiety-inducing — effect on Butterfly, as many Kendricks give voice to the many conflicts in his soul. Can he still speak for Compton now that he’s hobnobbing with celebs at the BET Awards? Or, more important, can he in good conscience be the musical darling of a country that enslaved his ancestors and continues to shoot down his people in the street unarmed? What does it mean to acquire wealth in a country that less than two centuries ago would have denied him the right to own property? These are the kinds of questions that have kept Kendrick Lamar up at night since he’s become famous, and we learn on Butterfly that his success rekindled a depression that he’d been battling since his teens. As it winds uninterruptedly through Lamar’s troubled consciousness, To Pimp a Butterfly doesn’t remind me of any recent rap record so much as it reminds me of Birdman, a formally innovative depiction of the angels and devils perched on a popular artist’s shoulders. (Also: jazz drumming.) “Loving you is complicated,” Lamar shrieks on the harrowing, impressionistic “u,” which unfolds more like a one-act play than a conventional rap song. At some point you realize he’s been delivering this monologue into a mirror.

But when Butterfly gets too stuck in its creator’s chatty brain, it’s the Mothership that brings it back down to Earth. Beginning with an opening-track blessing from none other than George Clinton (“When the four corners of this cocoon collide …”), the record is heavily indebted to the liquid groove of ’70s funk. Lamar’s great backing band — bassist Thundercat, drummer and occasional singer Bilal, backup vocalist Anna Wise, and saxophonist Terrence Martin — keep Butterfly moving on tracks like the bass-heavy grimace “King Kunta” and the swaying, Prince-esque “These Walls.” Like D’Angelo’s recent comeback Black Messiah, To Pimp a Butterfly is a record that finds liberation from present ills in the studio craftsmanship and heaving, live-band energy of the past.

In a moment when Drake is winningly experimenting with digital release strategies and Kanye West is talking so much about the future that he has felt the need to abbreviate it “the fütch,” Kendrick Lamar is the most nostalgic rapper at the top of the pack right now. When he painted his self-portrait on his famous 2013 guest verse on Big Sean’s “Control,” he was soaring high above his contemporaries, “bumpin’ Pac in the cockpit.” But oddly, it’s the ghost of 2Pac that occasionally leads Lamar’s opus astray. Between tracks, he repeats fragments of a 2Pac poem that begins, “I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence.” Did anyone really think that rap’s good kid Kendrick Lamar was misusing his influence? Lamar has painstakingly positioned himself as the most levelheaded, integrity-focused, fame-averse rapper in the game right now, and at its most overwrought, Butterfly spends too much time repenting for sins that no one was accusing him of committing in the first place. (Another thing we learned from the “Control” verse is that he hates fame so much that he cannot even pronounce Lindsay Lohan’s name.) To Pimp a Butterfly ends with a visit from Hologram 2Pac, in the form of an old Pac interview that Lamar has edited to make it seem as though he is asking the questions and conversing with his hero. But this moment backfires a little: By the end of the first question, you remember how much more charismatic — and genuinely funny — 2Pac was than Kendrick. Here, finally, is the man who actually embodied all of the contradictions with which Butterfly is so operatically grappling. It’s enough to make you miss him anew.

But these minor quibbles do not diminish the overall awe-inspiring achievement of To Pimp a Butterfly. It is the most grandiose American rap record since West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (a record that, like Butterfly, was both vital and imperfect), and it may very likely remain the most impressive release of the year. But if others fail to reach its heights, it may only be because they’re building empires elsewhere, not particularly interested Lamar’s classical, lyrically dense, substance-over-style approach. “I’m trying to raise the bar high,” Lamar prophesized on “Control,” and here at last he has succeeded — though in a lane with few living competitors. In the end, the challenge to surpass it might be yet another battle he’s only fighting with himself.

*This article appears in the March 23, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.