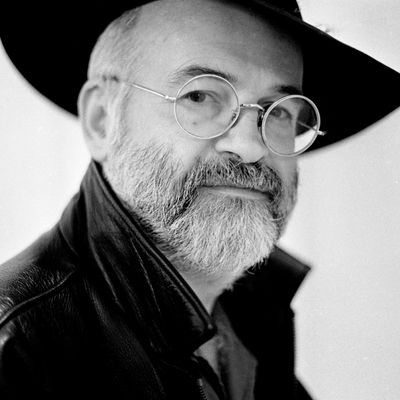

There’s part of you that wants to start channeling Pratchett’s character, Death, and (as the character did) start WRITING LIKE THIS AS IT’D BE NICE TO PRETEND YOU HAD ENOUGH DISTANCE TO JUST DO AN AFFECTIONATE HOMAGE.

But no.

With his announcement of tragic early onset Alzheimer’s in 2007, Sir Terry Pratchett’s death is a blow you were expecting. That doesn’t make it any easier. Doesn’t matter how many years’ warning you had, that extinction-level meteor strike crashing into Earth and sending continents sliding beneath the waves is still a bugger.

To the Americans, he was a cult success. To the British, it must be stressed, he was a phenomenon, the best-selling author of the ’90s. As such, the number of people this meteor has struck is more than a little overwhelming. The impact crater’s size makes makes me want to stop writing here and just give you my Twitter log-in details so you can scroll through my timeline and see the outpouring of memories of how much his work meant to people.

As I write this, my brother talks about his dyslexia and how Pratchett made him want to read even when his brain didn’t. I think earlier, and think of a teacher friend of mine who talked about the sheer number of children she taught who were brought into books by Pratchett. This reminds me how I was involved in a conversation earlier that compared him to Dickens, which struck me as correct. Massively popular writing powered by a strong sense of the pains of society. And then Pratchett added jokes, which makes him a dream mash-up of Dickens and Wodehouse, with a healthy sprinkling of genre just to ensure he got right up the right noses.

(“A complete amateur … doesn’t even write in chapters,” as the Late Review once said, the quote that was proudly printed at the front of a string of Pratchett books. The best revenge is always funny.)

Pratchett’s early books date back to 1971 with The Carpet People, but the Pratchett who cemented himself in the public mind was the writer of the Discworld books — originally a broadly satirical fantasy universe set on a disc on the back of four elephants on the back of an enormous turtle, which developed into a fantasy universe that could be used to satirize broadly anything (set on a disc on the back of, and so on, and so forth).

The first, The Colour of Magic, debuted in 1983, with the iconic, riotous, febrile Josh Kirby covers, which created the easy image of Pratchett in his critics’ minds as a parody of fantasy tropes. The third, Equal Rites, introduced what they tended to miss, starting his active desire to use the setting to explore bigger issues — in that particular case, sexism. The fourth, Mort, where Death decides he wants to take a holiday, was the first classic, and it all rolled from there in an extraordinary string of novels. Across the 40, with a 41st to be published posthumously, I struggle to think of a big issue he didn’t go to the mat and have a best of three with.

The jokes, the wordplay, the sentences were the style. We came to Pratchett for the substance, what he said about people. Pratchett fundamentally understood fantasy as a device for emphasizing humanity rather than escaping from it. You use the fantasy to make the point more precise, more undeniable, easier to digest, and impossible to refute. We can see ourselves more clearly. As core character and general force of nature Granny Weatherwax once put it: “Sin, young man, is when you treat people as things. Including yourself.”

Despite the core moral compass, a sermon wasn’t the point. This is moral rather than moralizing. When your core moral compass, as suggested above, is a militant empathy, then the characters have to embody that, even the villains — especially the villains. The one exception I can think of is his wicked deconstruction of all things elves in Lords and Ladies, and the attacking of the problematic core of the idea of “higher people” was very much the point.

By way of example, despite the fact that Pratchett was an atheist, Small Gods manages to brutally satirize religion while having at its core a sympathetic portrait of a prophet of a god in the body of a tortoise. Pratchett may not have believed, but he understood why people did. Both the practicing Catholic who first read it and the atheist who is writing this think it’s his best book, and if you’ve yet to read any Pratchett, Small Gods is where to begin.

I made a typo in that last paragraph, writing, “Pratchett is an atheist.” I moved the cursor back and corrected it to “was,” and the tears were in the eyes again.

We return to the empathy, and the power of leaving yourself open and opening others up. He made us fall in love with the most unlikely things, turning the things into people and making them our friends. As I write this, critic Cara Ellison writes to me, saying: “Pratchett wrote about Death and he made Death knowable, likable. There are so few writers who could make a million people across the world feel affection for death. Terry Pratchett made a whole generation of people fall in love with their own inevitable death.”

I cannot write this in isolation. I cannot write this alone, as Pratchett made me painfully aware that I’m not, and we’re in this together, for better or for worse, and that it’s generally “for worse” does not mean you get to stop trying.

While aware of it, while living through it, even I find myself blinking a little at the scale of his success. If Pratchett’s fiercely humanist, precisely angry books really are currently the second-most-read in the U.K., it’s the first time I’ve felt proud about my country for a long while. If that many people share Pratchett’s measured outrage, perhaps we’re going to be okay.