The WhitneyÔÇÖs new building allowed the museum to send curators deep into its archives to resurface artworks that hadnÔÇÖt been seen in many years and tell new stories. One of the more disturbing, and thought-provoking, moments in the inaugural exhibition, ÔÇ£America Is Hard to See,ÔÇØ are five prints of lynchings ÔÇö racially motivated murders in the guise of vigilante justice ÔÇö created by artists in the 1930s in protest of the then-widespread mob-rule barbarity. The Tuskegee Institute counts 117 African-Americans killed in this manner that decade.

ÔÇ£I knew that artists had treated the subject,ÔÇØ says Whitney curator of drawings Carter Foster. ÔÇ£When we realized we had them in the collection, we thought they would make a powerful group; theyÔÇÖre important images for people to see.ÔÇØ The lynching images, by artists including Jose Clemente Orozco, Harry Sternberg, Paul Cadmus, and Hale Woodruff, were previously collected in two exhibitions in 1935, both in support of an anti-lynching bill that was first proposed in Congress the previous year that had failed to pass and continued to languish decades later.

The first exhibition was organized by the NAACP at the Arthur Newton Galleries on 57th Street. NAACP leader Walter White put out a call for artists to respond to the bill. Another exhibition organized by the Marxist John Reed Club at the socially activist ACA Galleries on Madison Avenue followed under the argument that the NAACP show ÔÇ£wasnÔÇÖt broad enough,ÔÇØ says Mia Curran, a Whitney curatorial assistant who researched the lynching images. ÔÇ£Their show would encompass broader racial equality issues.ÔÇØ Some of the Whitney pieces, like the Cadmus drawing, appeared in both shows.

These larger tensions make the images especially pertinent 80 years later, in light of massive protests around the police killings of Eric Garner and Michael Brown as well as the recent uprising in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray. These events were ÔÇ£developing as we worked on this show, so itÔÇÖs not in response to that specifically,ÔÇØ Foster says. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs unfortunate that these are so timely. It shows that this problem is a long-standing one.ÔÇØ

We asked the curators for their thoughts on the individual lynching images in the context of the time of their making as well as our own.

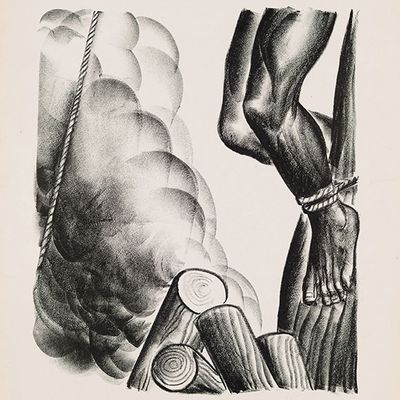

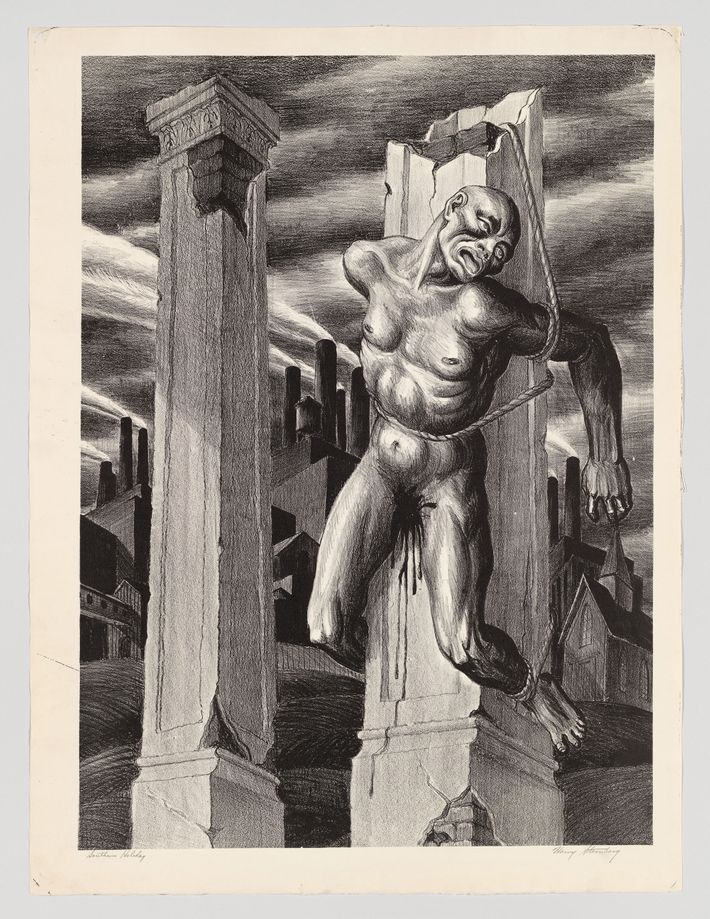

Harry Sternberg, Southern Holiday (1935)

SternbergÔÇÖs gruesome print is a direct reference to Claude Neal, a Florida farmhand who was accused of raping and murdering a 19-year-old white woman named Lola Cannady. Neal was arrested and charged with the crime, but the evidence was insufficient to convict him. Yet lynch mobs chased Neal from jail to jail. He was later tortured and killed, though not before he was castrated, ÔÇ£which was a common thing to do,ÔÇØ Foster says. NealÔÇÖs bleeding genitals are visible in the print. SternbergÔÇÖs image ÔÇ£turns it into a somewhat more symbolic spectacle,ÔÇØ Foster says. The contrast of rural and industrial urban space ÔÇ£suggests that weÔÇÖve made some progress in particular aspects of our civilization, but weÔÇÖre still doing barbaric things.ÔÇØ

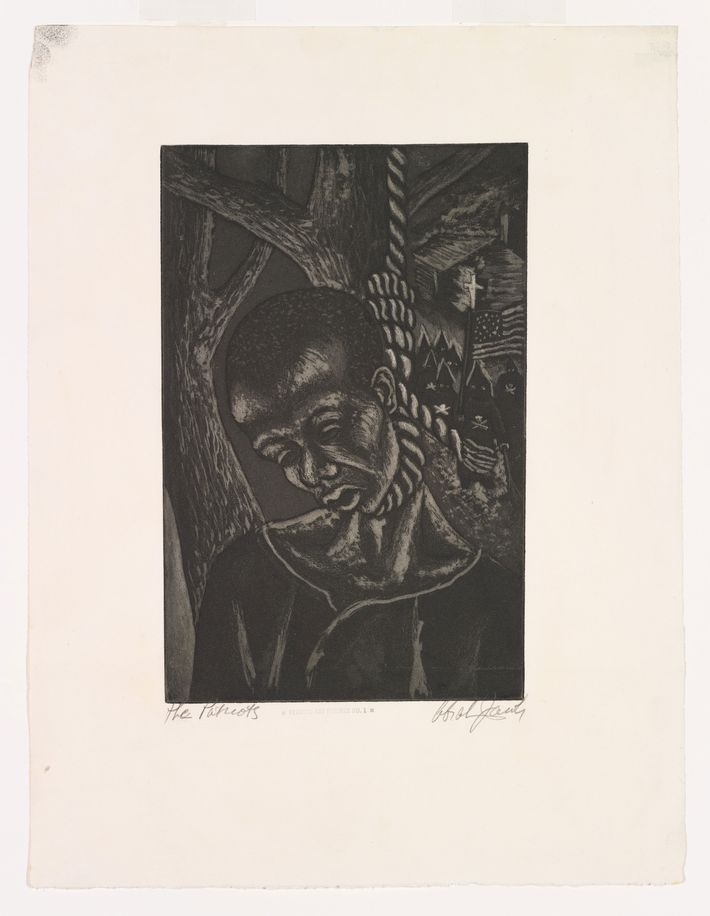

Abraham Jacobs, The Patriots (1937)

JacobsÔÇÖs print, made by etching and aquatint, shows a hanged man set against a group of KKK members and a burning cross. ÔÇ£Prints and politics really have their moment in the 1930s in the middle of the Depression,ÔÇØ Foster says. ÔÇ£Radically left artists used printmaking as more of a popular medium. It was easier to disseminate in periodicals and publications.ÔÇØ

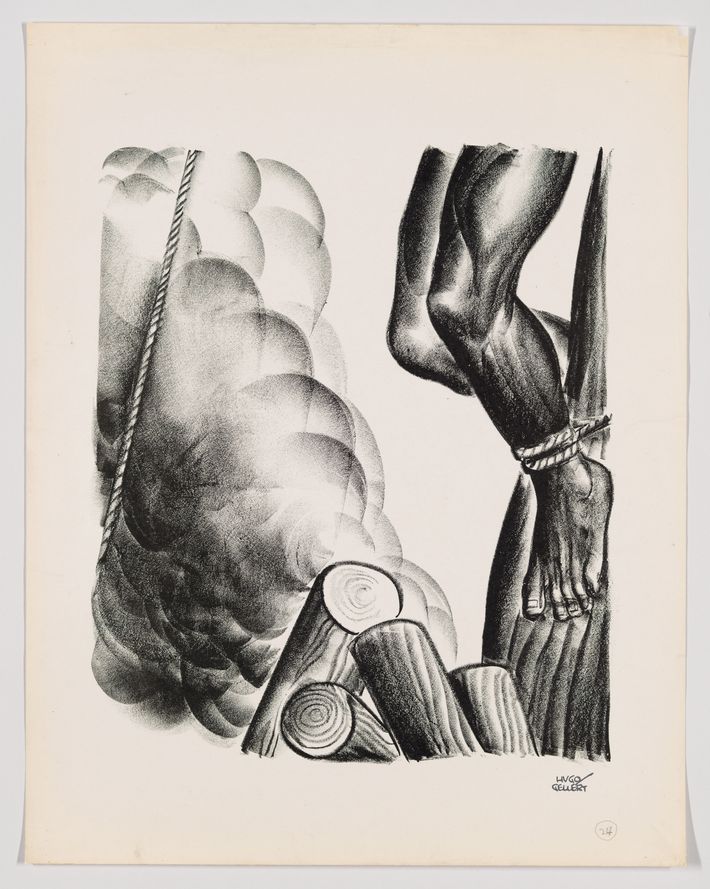

Hugo Gellert, Stake in the Commonwealth (1935)

Though the brutal act seems like it belongs to an earlier era of history, ÔÇ£the last public lynching was recently as the ÔÇÿ60s. It wasnÔÇÖt that long ago,ÔÇØ Foster says. This image was a print from Hungarian artist Hugo GellertÔÇÖs book Comrade Gulliver: An Illustrated Account of Travel Into That Strange Country the United States of America, which paired prints with a fiction story of a Soviet man traveling through the U.S. during the Great Depression. The artist was actively engaged in leftist politics and worked as a staff artist at The New Yorker, where he ÔÇ£was recognized for his bold graphic style,ÔÇØ Curran says.

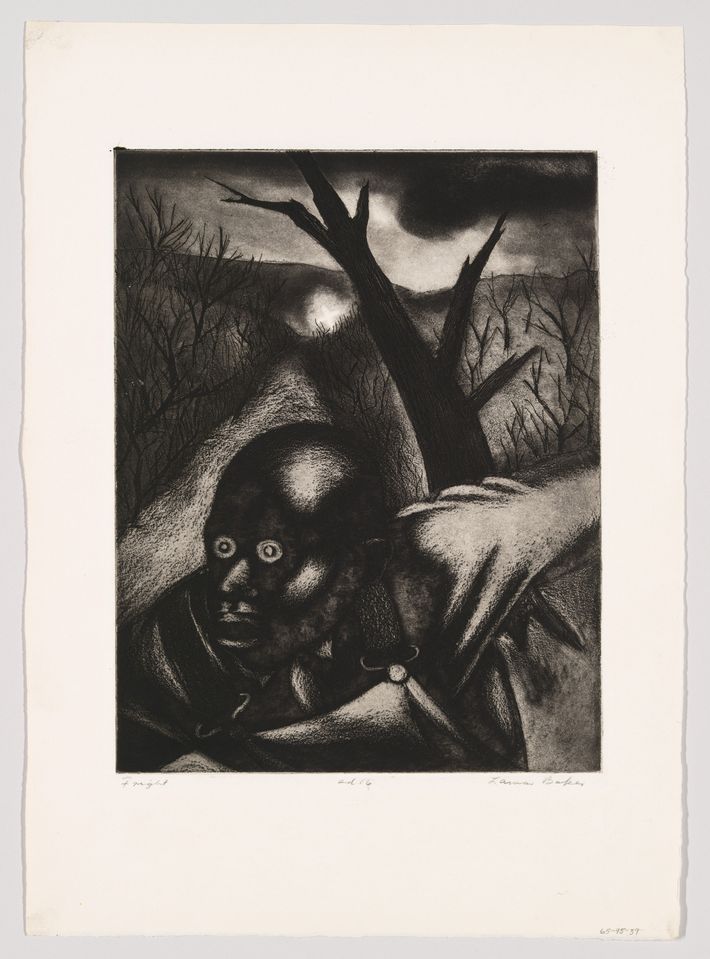

Lamar Baker,┬áFright (1936ÔÇô37)

Artist Lamar Baker was based in Georgia but studied lithography and etching at the Art Students League in New York under Harry Sternberg, who created Southern Holiday, seen above. Baker ÔÇ£was SternbergÔÇÖs student when he made Fright,ÔÇØ Curran says. ÔÇ£The terror in the manÔÇÖs eyes conveys the persistent fears of black Americans in the South during the 1930s.ÔÇØ In the background of the image, KKK members are illuminated and the suggestion of a burning cross is just visible ÔÇö the clear cause of the fear.

The Installation

ÔÇ£The salon style is a way to integrate multiple works on a wall together that are smaller scale,ÔÇØ Foster says. ÔÇ£All the works on that wall relate to the politics of that era and that decade, with lynching on the left and prints about labor and strikes on the right. ItÔÇÖs really about fitting both types of objects on a single flat plane.ÔÇØ The symmetrical arrangement plays up the repetition in the images themselves. ÔÇ£You have hanging bodies, faces with eyes ÔÇö it kind of echoes, making them all the more powerful.ÔÇØ The installation is a reminder that these incidents, like the police violence we face today, werenÔÇÖt isolated.