I wrote my second novel, A Little Life, in what I still think of as a fever dream: For 18 months, I was unable to properly concentrate on anything else. The book, which was published last month, is about four male friends who age from their mid-20s into their early 50s in an undated New York. The characters — Jude, JB, Willem, and Malcolm — aren’t based directly or consciously on anyone I know, and their professional worlds (law, art, acting, and architecture, respectively), aren’t ones I know firsthand.

But if the actual writing of the book was brief, it’s only now that I realize that I had been thinking of this novel for far longer. I began collecting photography when I was 26, 14 years ago; and when I actually began writing, it was these images I returned to, again and again: They provided a sort of tonal sound check, as it were — was I conveying in words and scenes what I felt when I saw these photographs and paintings? Now that the book is done, I realize that these images are now so inextricable from the book — and my experience of writing it — that looking at them again is somehow jolting: They’ve become a visual diary of that year and a half, and I find myself unable to look at them without thinking of the life of my novel.

Below is a short list of some of the artworks that informed and inspired A Little Life, in either subject or tone. Warning: Spoilers abound.

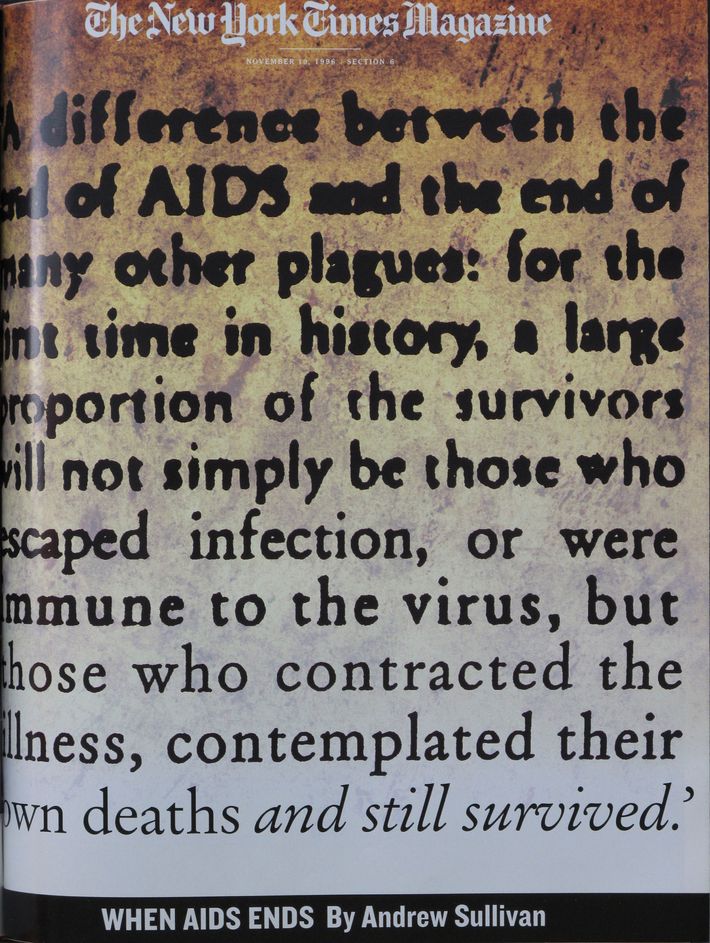

Chip Kidd for The New York Times Magazine’s “When AIDS Ends” cover, 1996; Prada fall/winter 2007 ready-to-wear show: One of the things I wanted to do with this book was create a protagonist who never gets better. I also wanted the narrative to have a slight sleight-of-hand quality: The reader would begin thinking it a fairly standard post-college New York City book (a literary subgenre I happen to love), and then, as the story progressed, would sense it was becoming something else, something unexpected. I turned repeatedly to two pieces of art to remind myself of this sensation. One of the ways I’d always described the book (to my editor and to my agent) was as a piece of ombré cloth: something that began on one end as a bright, light bluish-white, and ended as something so dark it was nearly black. I wanted it to approximate in language and feeling the pieces in Prada’s fall/winter 2007 ready-to-wear collection: skirts and jackets of heat-set, wrinkled woolen silks, their colors shading from pumpkins and greens into deep blacks. The other piece I returned to was Chip Kidd’s 1996 cover for a New York Times Magazine article by Andrew Sullivan about how combination therapies could mean the cessation of widespread death from AIDS in the United States, particularly among gay men. I remember being fascinated by the article, of course, but also by the cover, which remains one of my all-time-favorite pieces of editorial art: In it, the type starts out as “sick” — blurry, clotty, barely decipherable — and then, as it moves down the page, gets healthier, crisper, brighter, more legible. I wanted A Little Life to do the reverse: to begin healthy (or appear so), and end sick — both the main character, Jude, and the plot itself.

The Backwards Man in His Hotel Room by Diane Arbus, 1961: This photograph isn’t technically one of Arbus’s best — it’s slightly grainy, and it has a clumsy, voyeuristic quality that her later work doesn’t — but I have been captivated by it ever since I saw it in 2002. For a decade, I thought and thought about that image: I knew I had some words to put to it, but it wasn’t until I began writing this book that I knew that A Little Life would be, in some way, at least, the text that I’d write to accompany that photograph. Although I always describe the book as largely concerning itself with male friendship, I also intended it as a portrait of loneliness — specifically, the kind of loneliness that only city dwellers know.

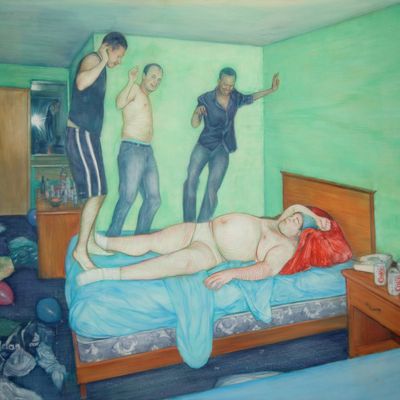

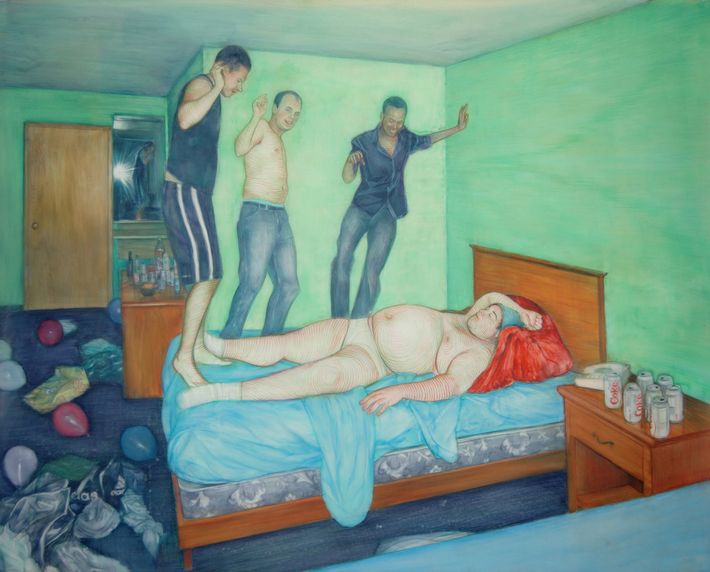

Boys in the Band by Geoffrey Chadsey, 2006: From 1999 through 2001, I was an editor at a now-defunct magazine about the media industry called Brill’s Content that eventually merged with a now-defunct website about the media industry called Inside.com. It was my first magazine job, and I found it terrifying, like being moved from the high-school literary magazine to the high-school debate team: Everyone was smart and facile and articulate and argumentative. One of my co-workers (and, eventually, one of my writers) was a man named Seth, and it was through him that I became friends with two of his friends from college: Joe, who was a copy editor at the magazine, and Jared, who was Seth’s former roommate and an editor at Inside.com. I found them all fascinating. I had attended a women’s college, and graduated into a women’s industry, and so this was the first time I was really getting to observe young adult males in action: the way they spoke to one another, how they expressed friendship, how they got angry or sad, the things they’d talk about with me but not with each other. I was also struck by their physicality, which young men express differently (obviously) than young women.

As I began writing, I thought a great deal about that particular brand of male unself-consciousness, which JB and Willem embody but which Jude cannot. One of the reasons Jude’s interior life doesn’t appear in the book until the second section was because I wanted the first section, which concentrates on the other three characters, to be, in a sense, a study of their normalcy, a foil to the strangeness of Jude’s own life. As I created Jude’s friends, I looked particularly to the work of Felix Cid and Ryan McGinley, both of whom capture so well that pleasure that young people take in their bodies, as well as this work by Geoffrey Chadsey. I’ve long been a fan of Chadsey’s, whose earlier works — about fratty boys, all young, dumb, and full of cum — are slightly winking, slightly leering portraits of male group intimacy, and their attendant and inevitable submerged homoeroticism. In an interesting footnote, I later discovered that Chadsey himself had been a friend of Joe’s at college, which meant that he and my other friends had all been in one another’s orbits, or near them, at the same time.

3878 from “Interiors/Motels,” by Todd Hido: Alec Soth, Joel Sternfeld, Todd Hido, Stephen Shore, PL diCorcia: There could be an entire show (and probably has been) dedicated to great American photographers’ images of American motels. There is something uniquely American about the motel: It speaks to the transient nature of America itself, one enabled and encouraged by our roads and highways. But they also remind me of the vastness, the unknowability of this country: These days, whenever I drive past one, I always wonder, What’s behind those curtains? How many lives will we never know? How many impossible stories have passed through those rooms, and have gone elsewhere, never to be found, never to be heard? It’s those questions that make possible Jude’s life, and it’s one of the reasons that I consider this a book, and a narrative, that could only take place in this country.

As readers of the book will know, a significant portion of Jude’s childhood is spent in motel rooms. Many of my significant childhood memories also involve motels; my family moved frequently, and we were often driving across the country, going from one place to the next. I still remember the particular bleakness of those one- or two-story structures, usually directly off the interstate, and the particular feeling of suspension — though of course I wouldn’t have been able to articulate that at the time — you experienced while staying in one. We would arrive at a motel late in the evening, and my brother and I would be instructed to sit motionless on one of the beds while my mother drove around whatever small half-town we’d stopped in, looking for a grocery store to buy bread and peanut butter for our dinner. I have never forgotten that sensation: the feel of the patterned polyester bedspread that matched the curtains, or the green carpeting worn shiny by hundreds of feet; or the sight of the television bolted to the wall; or the sound, like a river rushing, of cars zooming down the road just a few hundred feet away; or the expectancy I felt as we waited for my mother to return with our food. We were well-cared for, and protected, and there was never any question that she would come back to us, but I remember the moment as a hollow, empty one; it was one I knew Jude would feel as well as he waited alone in his room for his guardian, Brother Luke, to return to him.

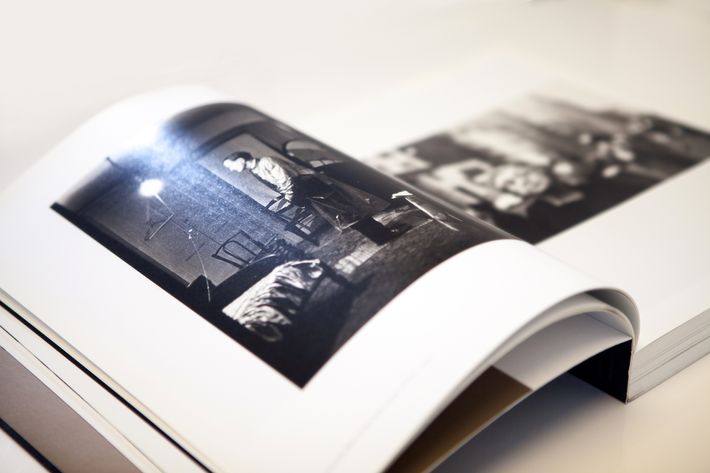

The Brown Sisters, by Nicholas Nixon, 1975–present: JB, one of the characters in the book, is an artist, but before I made him a figurative painter, I’d imagined him as a photographer, one whose life’s work would be two simultaneous series that documented his three friends’ lives. One of those series would be hundreds of casual, semi-reportorial “found moments”: Visually, I thought they’d look like a mash-up between Tina Barney and Nan Goldin. His second series, “The Boys” (I kept the name but applied it to something else), would be an annual black-and-white portrait of himself with his friends, always posed in the same order, shot against a seamless.

It quickly became clear that neither of these would work. The first wouldn’t work because of the sheer amount of time it’d take JB to accomplish it, and the sheer invasiveness of the project itself: All of the characters have busy, often peripatetic lives, and Jude in particular would never tolerate such a violation of his time and space. The second wasn’t going to work because it was a direct ripoff of Nicholas Nixon’s series “The Brown Sisters,” for which Nixon has shot his wife, Bibi, and her three sisters — always in the same arrangement — every year since 1975. Collectively, the photographs are as grave, moving, and chilling as you might expect: They illustrate perfectly the mercilessness of time, and the mercy of love.

One of the minor concerns my editor, Gerry, had about JB’s work was that he was too dependent on his friends for material — all of his series, save one, feature them in one way or another. (I believe the editorial notes “He needs to get a life!” were scribbled in red ink on one page or another.) But some of the greatest photographic series ever made are about a single life or set of lives, and the documentation of those lives can in fact be the stuff of an entire career, or at least many years. Nan Goldin’s iconic “Ballad of Sexual Dependency” is one such series. So is Nobuyoshi Araki’s chronicling of his wife, Yoko, which he began with Sentimental Journey, which was printed as a book in 1971, and concluded with Winter Journey — and Yoko’s death — in 1990. And I was particularly influenced by Andrea Modica’s beautiful series about a girl named Barbara in upstate New York. Modica began shooting Barbara in 1986, when the girl was 7, and continued photographing her until Barbara’s death from diabetes in 2001. The two resulting series — “Treadwell” and “Barbara” — are studies in compassion and, equally, in nuance and technical élan. In the same way as these series, I wanted this book to feel as if it contained entire lives, as if the reader is getting to pay witness to people they’re watching change, and grow, and stumble — to life itself — in a compressed amount of time and space.