The great, strangely stirring new Mountain Goats record Beat the Champ is ostensibly a concept album about wrestling, but it’s also an album about fandom writ large — how the seemingly trivial art forms we follow can help us learn to love, escape, and survive. The punchy single “The Legend of Chavo Guerrero” seems at first to be a ballad about the life and career of the El Paso–born wrestler, until front man/songwriter John Darnielle zooms out in the last verse: “He was my hero back when I was a kid / You let me down but Chavo never once did.” The forlorn final track “Hair Match” spells it out even more bluntly: “I loved you before I ever even knew what love was like.”

John Darnielle is a man of many enthusiasms (novel-writing being his most recent one; his unflinching debut Wolf in White Van was long-listed for a National Book Award last year), and anyone who’s ever seen him live knows that he brings an infectious energy not only to his songs, but to whatever he’s bantering about between them. Given the fan’s knowledge and loving attention to detail he brings to Beat the Champ, it’s no surprise that this is a man who could talk for almost an hour about the fine art of the wrestling promo. Below, Darnielle picks what he believes to be the eight finest examples of the form, from Macho Man Randy Savage’s quasi-Shakespearean coffee-creamer monologue to Luna Vachon’s Brechtian exorcism, and more.

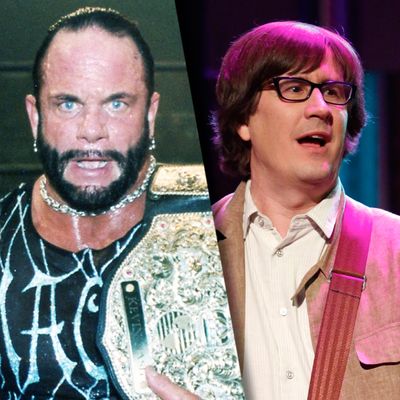

Macho Man Randy Savage: “The Cream of the Crop”

John Darnielle: Wrestling promos now, generally speaking … if they’re not completely scripted and TelePrompTed, they’re pretty close. But the old style of the promo was, “Look, we’re gonna do a little interview,” and then the wrestlers would generally come up with their own ideas. In the ’80s, they started to be a lot more stage-managed, because there are some guys who just can’t do it right. They’re good wrestlers, but they can’t ad-lib. It’s an improv skill — to be able to do a good promo, you used to have to be good on the mic. It’s like freestyling. And Savage could go at any time. The guy’s good for it.

My theory about this clip is that he was backstage and they were talking about who was good at promos, and Savage was like, “I bet I can do it with this creamer.” They probably had, like, a dollar bet that he couldn’t make the creamer work. And he just said, “Watch.”

He’s also doing sleight of hand here. He’s doing super-basic street magic, which is amazing. And then when he tries to balance the creamer on his head, he works the fact that it falls off into the script. It falls off his head, and he says, “On balance, off balance, it don’t matter, I’m better than you are.” This should be a text that is studied the way we study Shakespearean sonnets.

If you do something like that now, inside of three weeks you’re doing callbacks to it, and it’s like, it becomes this big thing. One of the worst things about the modern world is that if a person does something that’s cool, we just milk it until there’s not a drop left. But wrestling would move really fast back then, and you couldn’t watch the same thing over and over online, so things would sort of just have the mercy and grace to go away, instead of being dragged out again and again until everybody’s sick of it. We only have this one thing. He didn’t call back the Cream of the Crop or make his own Cream of the Crop T-shirts. It’s also, though, the fact that it’s on the internet now is why we’re able to recall it. Otherwise it would be, just like, some guy sitting around going, “Remember the one he did with the creamer?”

Hulk Hogan and Macho Man Randy Savage Join Forces

JD: At the time, these are the two largest stars in the WWF. Hogan is larger than life, he’s incredibly popular. Savage is getting popular, but he’s a heel. They are not allies, and they’re coming together to form an alliance. But they’re doing this amazing thing of pretending to be afraid to actually shake hands because there will be some giant energy popping off the handshake. The whole conceit of the performance is that the handshake might, as Hogan says, “blow up the whole planet.”

Either one of them is enough to have on one mic. You don’t need two of them in the same frame. It’s excessive. Have you ever heard the metal response to Band-Aid’s “We Are the World”? They formed this group called Hear ‘n Aid and did a song called “Stars.” And in the middle of “Stars,” every major pop-metal guitarist who was working at the time takes a solo. It’s like seven-and-a-half minutes long, and they all solo one right after the other, and then all these guys who have all this metal vocal range all come back on the mic at once, and it’s just like 40 guys going, “WE’RE STAAAAAAARS!” Right? This is sort of like that.

Luna Vachon’s 1993 WWF Raw Promo

JD: That is a stunning performance. You know, there’s a lot of camp in Savage and Hogan. It’s funny. They know it’s funny. It’s not a sense of you and me noticing it’s funny, but them not realizing. Everybody knows it’s funny. With Luna, that’s, like, a style of theater from the time of Brecht. Decadent prewar Berlin.

She used to do this thing where she would knock somebody down, and she’d be walking toward them to kick them some more, but then she would stop and physically just look like she was bathing in her own evil. It’s like if you’re on the dance floor and throw your head back and go, ahhhhh! just possessed by a feeling. She spends the promo doing that. Just sort of consumed by her own feeling for her character.

If you look at later interviews with her, I do think she spent a bit of her voice on her character. But you know, it’s like, sometimes, when you’re using it up, you’re like, “Well, what else is it for?”

Dusty Rhodes: “Hard Times”

JD: I mean, what can you say about the “Hard Times” promo? This is like a ’30s campaign pitch. It’s like something from the New Deal.

One great thing about wrestling promos is that they’ll try to make this small world of entertainment feel like it has a massive connection to larger things going on at the moment. Which it does, actually. Like when people say music is the healing force of the universe? Well, it’s true. But at the same time, you can step back from that and think, Well, no, I can’t … stanch bleeding with music.

So when Dusty Rhodes connects the struggle of scripted wrestling matches to a depressed economy, it’s both kind of absurd and kind of not. Because, even though it’s less so now, wrestling was a cheap ticket back in the day. So if you were working a 40-hour job and needed some entertainment to completely take you out of the annoyances of your daily grind, wrestling was the ticket. You’ll be so transported by the theater of it that you won’t have to think about your own stuff for three or four hours on a Friday night. So in a sense, he’s connecting to that. But he’s also trying to connect big sociological issues to this absurd theater. And it somehow hits both of those buttons at the same time. It’s perfect. It’s absolutely perfect.

Roddy Piper Hates Canada

JD: There was this Mexican wrestler named Black Gordman who would yell at the Mexican wrestlers in Los Angeles, as if he weren’t himself Mexican. He would do this character just to rile up the crowd. And the crowd at a Southern California match comes from a Mexican tradition, the lucha tradition. So it’s like singling out whoever would be most of the people in the room, and pissing them off. And Piper’s doing the same thing here. Because he’s a heel, he wants to make sure as many people as possible are angry at him.

He is Canadian, you know. He used to wrestle as a wrestler called “the Canadian.” As a masked wrestler when he was in L.A. It was a gimmick where he was called “the Canadian” and you were not supposed to know who it was, but everybody knew it was Roddy Piper. And so, for Roddy Piper to stand on a Canadian mic and play up Canadian stereotypes … there is no troll that has improved on this.

What he’s supposed to be doing is drawing heat. If your character’s a villain, you need to make people genuinely hate you. It’s not enough for people to know he’s supposed to be the villain, and everybody knows it’s fake, everybody knows that you are actually someone else. So the trick is to settle on something that hits people on a visceral-enough level that even though they know you’re only doing it to rile them up, they still can’t help but be angry. The heel is basically a little sibling. They find your button, and you know that’s what they’re trying to do, but you still get mad.

Ox Baker Threatening to Break Bones

JD: That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen. It’s 42 seconds. It’s 42 seconds of just threatening to break some guy’s bones.

[When I was growing up,] Ox Baker came to Southern California one week, and that was not his territory. I have theories about why he was there. My theory is, like, oh, he has family to visit, and he asked someone to give him some work to pay for the plane ticket or something. So one day this guy that I’d seen in magazines pops up on the screen, and he’s being interviewed, and he did his routine. He did this thing where he’s talking in this deep voice and he’s threatening to make people bleed and really hurt them.

There were only a couple people who would work that angle, that what they wanted to do was injure their opponent. Greg Valentine was one of the big ones. But Ox Baker also, he would wear a shirt that said, “I Like to Hurt People.” That’s an amazing shirt to see, most days. If you or I wear something like that, we’re winking. We’re not actually going to hurt anybody. But Ox Baker, in the era of kayfabe, you look at this guy and you’re forced to think, This is a person who has sought out a job that will specifically allow him to get away with breaking people’s ribs. And all these shirts, if you look at them, they’re felt-letter press-ons. He’s going to some place in a mall and being like, “Okay, yes, I need a thing that says, THE FANTASTIC OX BAKER” or whatever. There was a very self-made quality to all of this.

He was apparently one of the sweetest guys that ever lived, but on the mic, this was his deal. And you see also that he’s, like, two full feet taller than the interview. He’s just massive.

Captain Lou Albano and Greg “the Hammer” Valentine: “Unborn Virgin Calfskin”

JD: Lou Albano is not remembered as the great a worker he really was. I mean, that spiel … apparently, I have heard people say he was like that all the time. He’s not a character. He would do that for you at a bar, he would do that at any given moment. “Unborn virgin calfskin!” I don’t think there’s really anything we can say to improve on that.

Lou had some piercings, he actually pioneered this thing … he had facial piercings that he would put a rubber band through. There was one, like, in his cheek. And he’d put feathers from roach clips … just anything. His thing was sort of like, “What if I stick a pin in my face?”

One thing that a lot of wrestlers used to do would be they’d stand and boast about their clothing, and you’d say, “Well, actually, I find that clothing somewhat bizarre.” But if you listen to somebody boast about this stuff long enough, you sort of see it from their angle. Lou Albano is talking about his own glamour. And eventually you buy into it.

Zeb Colter and Jack Swagger Address Glenn Beck

JD: Glenn Beck said something insulting about wrestling fans. He called them “stupid wrestling people,” and wrestlers were really insulted. You know, the span of people at a wrestling match is not a single demographic of people. It’s not a single class or a single race, it’s really a very democratic sport, and lots of people from lots of walks of life enjoy it. But then Glenn Beck said some classist garbage about the people who go to wrestling matches. And these guys [Zeb Colter and Jack Swagger] jumped in and did this amazing thing where they’re like, “You’re only saying that because you’re a character yourself.”

Kayfabe is the name of the wrestling code meaning that you never break character. It used to be that if you were a really good worker, you would not break kayfabe. Because that does make it more exciting. If classic-rock dudes are playing a song, and they interrupt the lyric to comment on it? It can work under a certain hand, but it can also take you very out of the song. You don’t want to hear about other memories of the song. You want to live within that world. And that’s the function of it. A performance is this imaginary space. But in the ’80s, as TV and cable were becoming a thing and wrestling was becoming mainstream and wrestlers were starting to go on talk shows, it was becoming harder and harder to keep kayfabe. People started breaking the fourth wall.

If you didn’t know what was coming on this promo, how shocked were you when the green screen came up? It’s beautiful. And when they drop their character, they still have the same accents, so you can also see how they’ve folded some of themselves into the characters. But at the same time, the demeanor of Zeb Colter is this exaggerated thing. And Glenn Beck was mad specifically at Zeb Colter, because Zeb Colter’s character is a xenophobic tea party guy. His name is a play on Ann Coulter. So Glenn Beck was mad that they have a character who is a right-wing dude, which is so hilarious that he would be mad at this one character when there’s a whole span of characters of all walks of life, and they’re all hugely broad types and they’re all caricatures and that’s the fun. But people on the far right, as soon as one of them gets caricatured, they complain of persecution, because to complain of persecution is to get donations.

But that particular callout is so priceless: “We play a character and so do you.” Glenn Beck’s character does this thing where he pretends to inhabit it in a way that he won’t break that fourth wall on camera ever. Whereas in wrestling — and this is how wrestling fans, as readers, are sort of considerably more sophisticated than other readers — they’re able to sustain both knowing that it’s not real and saying, “But, well, there’s a different version of real.”

It’s like listening to somebody sing a song. If I sing about being love-stricken, and it’s a song I’ve sung 400 times, you know very well that that’s not what I’m going through at that time. I’m standing on a stage in whatever town I’m in. So it’s not my present-day reality. But we suspend all that and live in the fantasy in the lyric where the stuff is going on right then. And we’re able to do that. It’s a thing that’s miraculous about the mind and about text and about art.