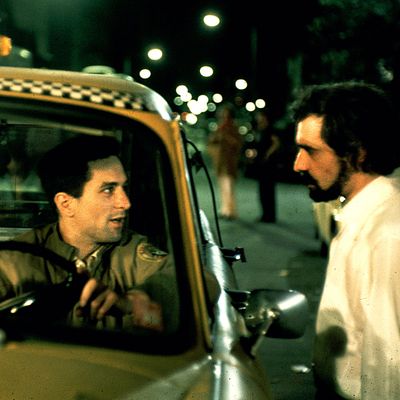

Last week, for its annual “Yesteryear” issue, New York Magazine published “New York After Midnight,” a celebration of the city after dark from a variety of writers and cultural figures. In honor of that, we went to the man who directed what may well be the greatest New York–by-night movie ever. The man is Martin Scorsese. And the film, of course, is Taxi Driver, a stylized, gritty 1976 portrait of a lonely cabbie’s descent into madness and violence in a hellish city. Emailing from Taipei (where he’s working on his latest film, Silence), Scorsese reflected on the experience of shooting Taxi Driver during one particularly grisly summer in New York City.

Taxi Driver often seems like a vision of hell. Did you have to do anything special to make the streets seem like Hell? Or were they pretty much already pretty hellish?

It was a rough period in the history of New York — as a matter of fact, the famous Daily News headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead” came out while we were editing. Although I couldn’t tell the difference. Apparently, the city felt like it was falling apart, there was garbage everywhere, and for someone like Travis, who’s come from the Midwest, the New York of the mid-’70s would be hell — [that] must have prompted visions of hell in his mind. But one thing I can tell you: We didn’t have to “dress” the city to make it look hellish.

Did using real-life locations ever cause any problems?

Location shooting always presents problems — getting the permits, dealing with street noise, camera movement in actual locations. For instance, the tracking shot over the murder scene at the end, which was shot in a real apartment building: We had to go through the ceiling to get it. It took three months to cut through the ceiling, and 20 minutes to shoot the shot.

You’re shooting on-location at night, and you’ve got actors playing characters who could conceivably be walking these streets. Did Robert De Niro ever get mistaken for a real cabbie? Did Jodie Foster ever get mistaken for a real prostitute?

Well, obviously, it all happened pretty close to the bone — the difference between what you see on the screen and what was happening on the streets at the time is pretty slight. I can tell you that Bob De Niro got a hack license in preparation for the movie. One of his passengers recognized him from Godfather II, for which he’d won an Oscar, and he said, “Gee, I guess it’s tough to find work.”

You had shot parts of Mean Streets in Los Angeles. Given some of the challenges of shooting Taxi Driver, did you at any point wish you’d gone back to L.A. to shoot it?

It’s the other way around: I wanted to shoot all of Mean Streets in New York, but I couldn’t afford to. I’m happy with the way it turned out. But with Taxi Driver, I was fortunate to be able to shoot every inch of it in the city. The difficulty of shooting on the streets of New York finds its way into the fabric of the picture, in ways that I can’t really articulate. For the same reasons, it would never have made sense to shoot New York, New York anywhere but Hollywood, where I could reinterpret New York in the classic Hollywood studio tradition.

There was both a heat wave and a garbage strike during the time you were shooting Taxi Driver. What kinds of challenges did that present?

Big ones. But it was great, because it was all perfect for the movie. Truffaut made a statement right before he died, about the fact that when you’re making a movie, you’re in something like a fugue state. So difficulties and opportunities and mistakes and surprises and grace notes all blend together.

In the scene where you’re playing Travis’s passenger, I read that De Niro actually gave you some direction. Is this true? What did he say? And how did you come to play that part?

George Memmoli, who appears in Mean Streets, American Boy, and New York, New York, was supposed to play the part. George had an accident, and I stepped in. Did Bob give me direction? He gave me an action — I had to make him keep the meter running. We worked it out between us.

Today, many of us see Taxi Driver’s New York — particularly midtown — as a city that doesn’t exist anymore. Did it ever occur to you while shooting the film that this world wouldn’t exist anymore, that the film would feel like a time capsule?

That’s an interesting question. Really, you could ask the same question about any picture made on-location in New York during any era. Now, for instance. Will all these clean, scrubbed surfaces stay so clean and scrubbed? Will all these glass towers be standing in 100 years? Will Manhattan be as becalmed and kind of domesticated as it is now in 20 years? Fifty years? I don’t think we had a consciousness of this question while we were shooting. I know that Woody Allen, quite beautifully, actually set out to create a time capsule with Manhattan, but that’s something entirely different: different story, different way of life, different New York.

How does shooting at night in New York today compare to what it was like back then?

It’s more orderly, I suppose. A little easier. I suppose that’s indicative of the fact that the city is now pretty well-managed and operated. The downside, of course, is that it’s now so expensive to live here. I seem to remember that Patti Smith told an audience, if you’re young and you want to be an artist, don’t come to New York. Sad to say, I agree with her. On the other hand, as the father of a teenager, I’m glad that the city is so much safer. For the moment …