ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs an old firehouse, so this is probably where the fire engines were kept and washed,ÔÇØ said Huma Bhahba as we roamed into her expansive studio in Poughkeepsie, New York. Born in Karachi, Pakistan, in 1962, Bhabha has lived upstate for 13 years. She occasionally teaches at Bard College in the summer MFA program, but the appointment wasnÔÇÖt the reason for landing in the region. ÔÇ£It was because I knew somebody who had moved here who was an artist. I started teaching at Bard much later. IÔÇÖve been here about 13 years.ÔÇØ After completing her MFA at Columbia University, Bhabha lived in New York for 13 years before abandoning it owing to rising real-estate prices. About living outside the gravitational pull of the city, Bhahba confirmed, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a shock but you can manage it.ÔÇØ

BhabhaÔÇÖs studio floor and walls were covered in brick tile ÔÇö a pattern the artist covered with paper and stepped on while working to create a frottage effect for several works on paper in her current exhibition at Salon 94ÔÇÖs downtown galleries, on view until June 28.

Although this show focuses on BhabhaÔÇÖs two-dimensional work, the artist is best known for her grotesque yet monumental sculptures born out of ancient tribal artifacts, German Expressionism, and popular science-fiction influences such as those in her recent exhibition at MoMA PS1 of otherworldly figures appearing in a state of decay.

In her current exhibition at Salon 94ÔÇÖs Bowery location, the rubber-sole patterns of BhabhaÔÇÖs treads repeat in the bronze The Escapist (2013) of three loosely braided tire tracks that lay flat near the feet of Constantium, 2014. The latter ÔÇö a figurative, totemic bronze ÔÇö stands guard as you descend into the subterranean, high-ceilinged gallery, a.k.a. her tomb. Originally carved from cork, the figureÔÇÖs lines and crevices are deeply crenulated. Crude chalklike marks indicate humanoid features such as eyes and breasts. But hair, or maybe a swath of tentacles, covers where a nose and mouth would be ÔÇö a look that references tribal masks, veiled women, and a Chewbacca/Pac-Man in equal parts.

The sculptureÔÇÖs base was cast from an object a friend had given her ÔÇö a hinged, cabinetlike object. ÔÇ£I hadnÔÇÖt even thought of this part as being part of the sculpture. I just wanted to place it on a higher surface, and this was lying around my studio. I liked the complication of the chain. It opened up another aspect to the work,ÔÇØ said Bhabha about the thread attached to the doorÔÇÖs lock which drapes up over the figureÔÇÖs head and around her neck ÔÇö part adornment, part a tethering to an underground world that this bronze no doubt has keys to.

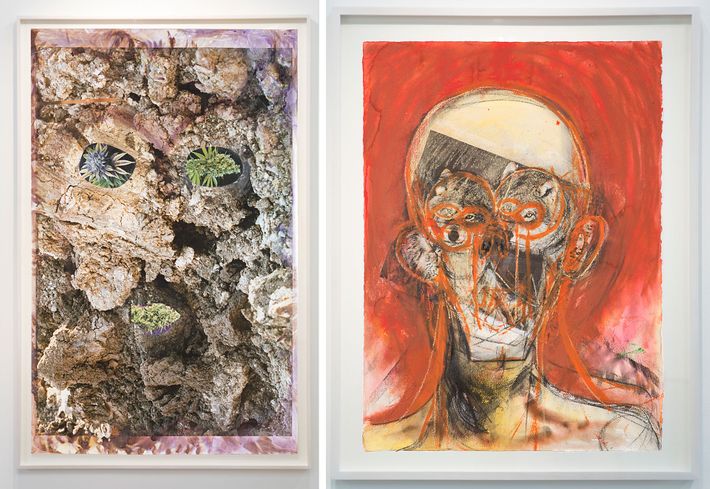

The second half of the exhibition, around the corner and inside Freeman Alley, features two-dimensional works of BhabhaÔÇÖs drawings with collaged photographs. From afar, the works are color-saturated portraits of animalistic yet alienlike heads that upon closer inspection reveal photos of dog breeds and wolves sourced from Hallmark-esque calendars and cannabis hybrids lifted from the magazine High Times. The unusual juxtapositions say: Would not some future anthropologist deem our pot-smoking and internet obsession with frolicking puppies as significant cultural rituals? We certainly clock an inordinate amount of time at both. But the works also point to perhaps that dogs should be treated, now, as the spirit animals they are.

Back at BhabhaÔÇÖs studio, ConstantiumÔÇÖs sister ÔÇö the artist proof of the series ÔÇö had taken up permanent residence in BhabhaÔÇÖs backyard. Taped above BhabhaÔÇÖs drawing table, photos of wolves were interbreeding with images of silverback gorillas, a Sigmar Polke, and a Gauguin, among other ephemera. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve been doing drawings with wolves as collage material for about two years now,ÔÇØ said Bhabha. ÔÇ£These are kind of just there ÔÇö IÔÇÖm not going to use them. I just like looking at them. I like using animals. I was using some wildlife and before that ÔÇö Jack Russells.ÔÇØ I asked if the one on her table was her own Jack Russell, Duncan, who had just joined us. ÔÇ£No, this photo was from a calendar. Even for the ones that have wolves in them ÔÇö they are also from a calendar.ÔÇØ Both in BhabhaÔÇÖs exhibition and in her studio practice, you could sense a slippage, an easy transference, between popular culture and the visual language of mythologies past. ÔÇ£I like dogs, and wolves, and animals, and werewolves,ÔÇØ she stated.

The sculptural materials that Bhabha manipulates into abstractions of bone, flesh, and organs were all at hand. Towering by the studio entrance, Styrofoam forms awaited their next reincarnation. Along the opposite wall, a selection of cut wood rested in a curated row, and, nearby, a collection of various metal scraps mingled inside a basin. ÔÇ£Ever since IÔÇÖve been making work, IÔÇÖve been collecting objects and using them to add to the work. So, itÔÇÖs always sort of a bit of an assemblage.ÔÇØ While most of the objects are found, Bhabha remarked that often people save interesting pieces to give to her.

I spotted a wood figurine on her table. ÔÇ£It belonged to my parents, but itÔÇÖs not an antique or anything. I always liked it, and now IÔÇÖm aware of how much my work relates with African sculpture.ÔÇØ I asked when her first encounter was with that visual language. ÔÇ£I think the first time I saw a really amazing, beautiful, and dense exhibition was at the Museum of African Art when it used to be on Broadway [at the site of the former New Museum] many years ago. A friend of mine was working at arranging the space.ÔÇØ I asked if her work revealed the influence shortly thereafter. ÔÇ£No, I wouldnÔÇÖt say that. You realize it a bit later. It took a while.ÔÇØ

I asked Bhabha a bit about her process. ÔÇ£I make a lot of decisions while IÔÇÖm working on a piece. Even though you conceive of everything beforehand, you let it play out. So far, the changes have been for the better. You realize at a certain point where something is going or not.ÔÇØ Bhabha prefers to work alone with no assistants ÔÇö aside from a few tasks needing a hired hand. ÔÇ£When IÔÇÖm working on pieces, there is a lot of time spent looking and figuring things out, and I canÔÇÖt work with another person hanging around.ÔÇØ

Next to the bronze figure in the back terrace, animal skulls were piled in a chair. ÔÇ£I used to work at a taxidermy place between 2002 and 2004. When I first moved here, that was my job. These are the skulls they didnÔÇÖt want. Usually they keep more exotic skulls like certain cats or baboons. Hunters like those as trophies. But these are antelopes, which they normally donÔÇÖt care for. The animal skin is stretched over a form made of hard foam, so the actual skull is not needed. My job was sculpting the eyes, noses, and mouths that were eaten away by the tanning process. I have used some of the skulls in my work ÔÇö maybe two or three.ÔÇØ

A weathering heap of car tires rested next to the skulls. ÔÇ£The tires IÔÇÖve been using for the last three years. About an hour from here, thereÔÇÖs a tire recycling plant and you can pick up all kinds of tires. Some friends have given me some and two were my brotherÔÇÖs. TheyÔÇÖre a material, and itÔÇÖs good that they can be kept outside. Soon IÔÇÖll be cutting these up.ÔÇØ

Huma BhabhaÔÇÖs exhibition at Salon 94 Bowery and Salon 94 Freeman will be on view until June 28.

Sarah Trigg is the author and photographer of STUDIO LIFE: Rituals, Collections, Tools and Observations on the Artistic Process.