The blockbuster ÔÇ£Looking Forward to the PastÔÇØ sale at ChristieÔÇÖs on Monday night was a tough act to follow, but results from the evening sales of postwar and contemporary art at SothebyÔÇÖs and ChristieÔÇÖs proved it was no fluke: Yes, the art world is still awash in cash. By the close of the auction week, close to $2 billion will have traded hands. The gold rush continues ÔÇö and ChristieÔÇÖs is holding the most shovels.

The two auctions were stacked with iconic names and classic examples of artistsÔÇÖ signature work. At the events, the bids became a real-time way to track these artists against each other by collectorsÔÇÖ enthusiasm. Wool or Polke, V├┤ or Frankenthaler: WhoÔÇÖs on your art-world fantasy league team?

On Tuesday, SothebyÔÇÖs auctioneer Oliver Barker played to a packed house, skillfully milking bids from all corners to deliver $379,676,000 on 55 sold, the houseÔÇÖs second-highest total for a contemporary sale (after November 2013). The pacesetters were a group of nine lots earning $15.9 million that were auctioned to benefit the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Front-loaded in the lineup, both Mark BradfordÔÇÖs mixed-media Smear┬á(2015) (est. $500,000ÔÇô700,000), and Mark GrotjahnÔÇÖs densely textured Untitled (Into and Behind the Green Eyes of the Tiger Monkey Face 43.18)┬á(2011) (est. $2ÔÇô3 million), caused a clamor in the sale room, with no fewer than ten bidders apiece pushing their final (and record) prices to $4,394,000 and $6,522,000, respectively.

ÔÇ£It was really a rush,ÔÇØ remarked international co-head of contemporary art Alex Rotter.

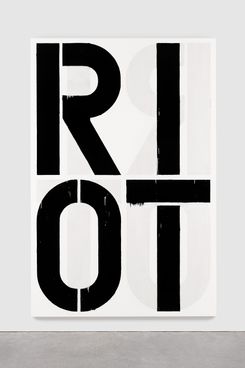

Soon after, a late Warhol, Superman┬á(1981), soared past its $8 million high estimate on the way to $14,474,000, and the pump was primed for Christopher WoolÔÇÖs enamel on aluminum Untitled (RIOT)┬á(1990), a textbook example of the artistÔÇÖs early black-on-white text-based paintings (and a timely entry considering recent events) estimated to fetch $12ÔÇô18 million. There were a few tense moments as Barker dangled the opening price of $9.5 million in the air. Somewhere in the bowels of the building, an alarm sounded. Then the race was on, with private dealer Philippe S├®galot jousting with Larry Gagosian and senior specialist Gr├®goire Billault on the phone. Billault finally won it for $26.5 million at the hammer, with a buyerÔÇÖs premium nudging past the $26,485,000 record set by Apocalypse Now at ChristieÔÇÖs in 2013, to $29,930,000. Said a relieved Barker after the sale, ÔÇ£The Wool seemed to take forever to take off, but when it did, it really did.ÔÇØ

The next lot was another home run. A major Sigmar Polke, Dschungel (1967) (est. in the region of $20 million), rocketed beyond the standing $9,245,139 artist record to $27,130,000 on fumes from his traveling retrospective. But the saleÔÇÖs top prices went to Mark RothkoÔÇÖs Untitled (Yellow and Blue)┬á(1954) ÔÇö which was pursued by multiple bidders to $46,450,000 ÔÇö and Roy LichtensteinÔÇÖs The Ring (Engagement)┬á(1962), from the collection of Stefan Edlis, which a buyer on the phone with Patti Wong, chair of SothebyÔÇÖs Asia, put a ring on for $41,690,000. Both, however, were on the low end of their estimates.

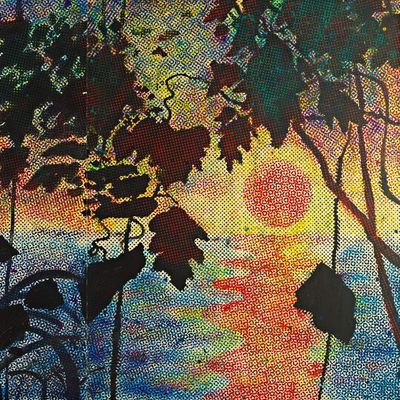

Further records were established for Thomas Struth, Danh V├┤, and Helen Frankenthaler, who at last cracked the $1 million mark with a lengthy tussle over the color-saturated acrylic on canvas Saturn Revisited┬á(1964), which rose well beyond its $600,000ÔÇô800,000 estimate to claim $2,830,000 from a phone bidder.

Noting the wide spread of eras represented in the top-earning lots, a beaming Rotter said, ÔÇ£We chose the right works and were highly rewarded.ÔÇØ

ChristieÔÇÖs, however, bulldozed its rival with a $658,532,000 take on 72 sold lots last night, though the number of guarantees and third-party financing deals leaves the private companyÔÇÖs profit picture murky. Things got off to a strong start when┬áTorsione┬á(1968), a metal-and-flannel sculpture by Italian Arte Povera artist Giovanni Anselmo, went for a record $6,437,000 ÔÇö more than eight times its estimate ÔÇö while some attendees were still trickling in from the Frieze VIP collectorsÔÇÖ preview. The message? You snooze, you lose ÔÇö and sometimes you still lose, for during the course of the next two hours, a good many well-financed dealers found themselves shut out of the hunt by the faceless global rich calling in from their Learjets or parts unknown.

They went after trophy pieces like RothkoÔÇÖs No. 10┬á(1958), an imposing canvas that glowed like a fading ember and attracted at least five serious telephone bidders represented by a cast of house reps with connections to China, South America, and Europe. Bidding opened at $40 million, above the weekÔÇÖs previous prices for Rothkos. A hush fell over the crowd as the contest narrowed and Jussi Pylkk├ñnen asked, ÔÇ£Will you give me $72 million?ÔÇØ Specialist Ana Maria Celis obliged, but her colleague, director of business development Lisa Layfer, countered and won the picture for $73 million, or $81,925,000 with fees ÔÇö only slightly shy of the Rothko record of $86,882,496, paid for Orange, Red, Yellow from 1961 at ChristieÔÇÖs in May 2012. After the sale, Brett Gorvy waxed rhapsodic about work, calling it ÔÇ£a measure of the greatness thatÔÇÖs still out there in the market,ÔÇØ and thanked the ChristieÔÇÖs lighting team ÔÇö you canÔÇÖt forget about the lighting team! ÔÇö for showing it off to its best advantage.

Buyers bid high for Bacon, too. Portrait of Henrietta Moraes┬á(1963), featuring the titular muse against a lurid purple ground, seduced several bidders, ultimately selling to Brett GorvyÔÇÖs client for $47,765,000. The hammer price was barely beyond its $42 million estimate but was still a win for the consignor, who acquired the painting for about $33.5 million at ChristieÔÇÖs London in February 2012.

Arguably the finest piece in the sale, however, was Lucian FreudÔÇÖs Benefits Supervisor Resting┬á(1994), a colossal accomplishment of figure painting (not to be confused with the similar but lesser Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, which set the artistÔÇÖs record of $33.6 million at ChristieÔÇÖs in May 2008). Tagged at $30ÔÇô50 million, it was bound for record territory, and London dealer Pilar Ordovas did not flinch in pulling the trigger for $56,165,000.

That price was matched by Andy WarholÔÇÖs Colored Mona Lisa┬á(1963) (est. in the region of $35 million), painted more than three decades earlier but still arrestingly contemporary. It was won by Larry Gagosian, who also shelled out $42,725,000 for a lovely large Cy Twombly ÔÇ£BolsenaÔÇØ painting from 1969 (est. $35ÔÇô55 million), beating out dealer Robert Mnuchin and a client on the phone with the houseÔÇÖs Lo├»c Gouzer. Gogo still had enough change left over to pick up the final lot, Jeff KoonsÔÇÖs Balloon Monkey Wall Relief (Blue)┬á(2011) ÔÇö a $965,000 donation to the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children.

Against figures like these, itÔÇÖs somewhat shocking that a Robert Rauschenberg combine once owned by Ileana Sonnabend ÔÇö┬áJohansonÔÇÖs Painting, featuring a shaving brush, tin can, and artistÔÇÖs frame ÔÇö could be had for ÔÇ£justÔÇØ $18,645,000, and an artist record at that. New benchmarks were also set for Robert Ryman, Carroll Dunham, Hans Hofmann, Sturtevant, and Rudolf Stingel.

But despite strong numbers, not all were convinced of the price-to-quality ratio. Art adviser Wendy Cromwell, of Cromwell Art LLC, commented, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs theatre of the absurd when an important Glenn Ligon painting sells for a fraction of what an abstract composition by Chris Wool does.ÔÇØ

Whatever the bidders raise their hands for, the prices keep getting higher. Says Gorvy of the new breed of buyer, ÔÇ£They like the competition, to see others bidding on the works. It gives them confidence.ÔÇØ But a herd mentality couldnÔÇÖt save WoolÔÇÖs word painting Hypocrite, 1990, pegged at $15 million to $20 million: It found no takers.

Phillips, flaunting a potentially potent mix of established names and wait-list-only newbies, takes the podium at 7 p.m. tonight, which may be the truest test of the depth of the market for contemporary art. While its larger competitors increasingly pursue the bluest of blue-chip trophies, Phillips has the opportunity to demonstrate that thereÔÇÖs demand for the icons of tomorrow as well as today.