Art made with technology, no matter how cutting-edge, always has a way of becoming kitsch. Think Nam June PaikÔÇÖs cathode televisions or Cory ArcangelÔÇÖs self-consciously obsolete video of hacked Super Mario clouds. A work becomes successful when it can both incorporate the technology and exploit it for its ephemerality. Artist Tabor Robak, born in 1986 and certainly part of a millennial technological cohort, hits a sweet spot.

The uniform slickness of RobakÔÇÖs computer-graphics renderings of sometimes-mundane, sometimes-extraordinary objects and technological interfaces might look recognizable from contemporary video-games. But in reality, they are exponentially more elaborate. Robak models his videos by hand, exploring the medium of CGI the way Michelangelo did marble. ItÔÇÖs an arduous, individual process ÔÇö one hand on one mouse ÔÇö but itÔÇÖs executed in a way possible only in the 21st century.

Rather than crunching them himself, Robak sends his enormous files, so large precisely because theyÔÇÖre hand-modeled, out to a ÔÇ£render farmÔÇØ where the data can be processed quickly. ÔÇ£Ours is in Florida in someoneÔÇÖs garage or something. A guy with a ton of computers,ÔÇØ says Todd von Ammon of TEAM gallery, where Robak is mounting a solo exhibition called ÔÇ£Fake ShrimpÔÇØ┬áthrough June 7. The artistÔÇÖs engagement with both the aesthetics and the mechanical processes of technology bring to mind similarly buzzed about names like Artie Vierkant and Katie Steciw.

ÔÇ£Fake ShrimpÔÇØ is composed of just a few pieces, hinting at the time required to complete the work. WhereÔÇÖs My Water is a wall-size array of televisions that beam a composite detailed animation of pens in cups, suggesting a vast, surreal collection of desk surfaces. Butterfly Room, in contrast, is a digital bestiary of creatures fluttering in a grid of tiny LCDs. Robak led us through the intricate pieces in the show and explained the digital workflow needed to sculpt in pixels.

Newborn Baby

This three-panel work features two transparent LCD screens that splash pixels in an invisible layer over the top of more traditional television panels. The animation itself displays the building blocks of visual culture: letters, symbols, and diagrams evolving into kitschy high-definition footage of wild animals. ItÔÇÖs a deconstruction of the way we see, both onscreen and in the physical world.

Tabor Robak: I took inspiration from textbooks about vision and baby visual stimulation cards I did when I was a kid. IÔÇÖd like to get some babies in here and park them in front of it. I think itÔÇÖd get them ready.

Maybe a year ago I saw some random YouTube video of these transparent screens existing. I just searched the internet until I found one I could buy. I had no clue if these things were going to work. It sounded too good to be true. ItÔÇÖs a fantasy thatÔÇÖs been promised to us by science fiction. Then you get them and theyÔÇÖre very material. TheyÔÇÖre not totally clear, itÔÇÖs kind of brown, grids overlap, pixels create a moire pattern. ThereÔÇÖs a wonderful distance between what you expect of a transparent screen and the transparent screens we have. I love the way they look.

WhereÔÇÖs My Water

On a wall-size grid of screens, Robak displays a kind of animated slideshow of various cups filled with pens, among other objects ÔÇö the tools of creative work. The visuals symbolically hint at the artistic process, but the execution is all about labor as well. The pens, cups, and abstract patterns of the video are hand-modeled in a process that taxes even powerful computers.

Robak: I started noticing pen cups all over the place, seeing them in a laundromat, a friendÔÇÖs home, at TEAM gallery. ItÔÇÖs this little picture of a person, in a way. I started making pens and getting so obsessed with detail, trying to work on it at a huge scale. The computer doesnÔÇÖt like it, but I enjoy it. The flowerpot one is definitely modeled after my aunt. You clearly get an idea of a crafty mom or something. A couple are in a total fantasy world, like the one thatÔÇÖs stabbed through with pens.

I have a specific way of rendering objects, which is not just iconic but almost like a shared ideal image, in a way. ThatÔÇÖs also captured in the way that the objects are lit with a heavenly glow, a little sparkle. I go with what the tool naturally encourages. It does shiny surfaces really well, so itÔÇÖs a shame not to use shiny surfaces.

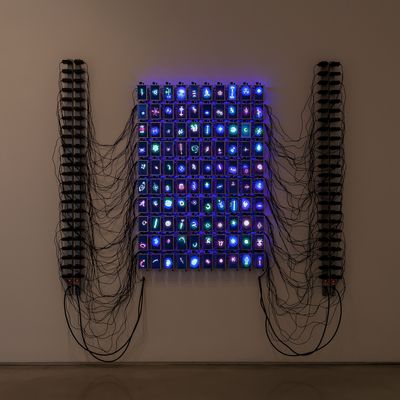

Butterfly Room

A grid of small screens is rigged up with very visible wiring to make this bestiary of digital creatures. Each animation, made up of tiny tubes, spikes, and whirring legs, like a biologistÔÇÖs encyclopedia of cells, lives its own unique existence in loop of video a few minutes long. The piece is an exercise in playing a digital god.

Robak: A lot of the work in the show is about work, is about making. I wanted to make something that I hadnÔÇÖt made before, make something more with my hands, from scratch, not like with these big TVs. I dove into working with electronics and didnÔÇÖt know where it would take me.

This piece reminded me of this Pok├®mon poster I had as a kid, with all the Pok├®mon laid out. The size of those screens is kind of like a little vessel to put a creature in. I went through the exercise of creating these little characters ÔÇö thereÔÇÖs a little bit of a genealogy through them, it just naturally happened in the process of making 100 of them. ThereÔÇÖs an evolution in them.

With the hardware, I can make it as elegant as I can, but thereÔÇÖs no way to hide it. ThatÔÇÖs just part of the nature of it, in a way, another feeling of creation. ItÔÇÖs┬ákind of like these little creatures are on life support or theyÔÇÖre stuck on an electric fence.