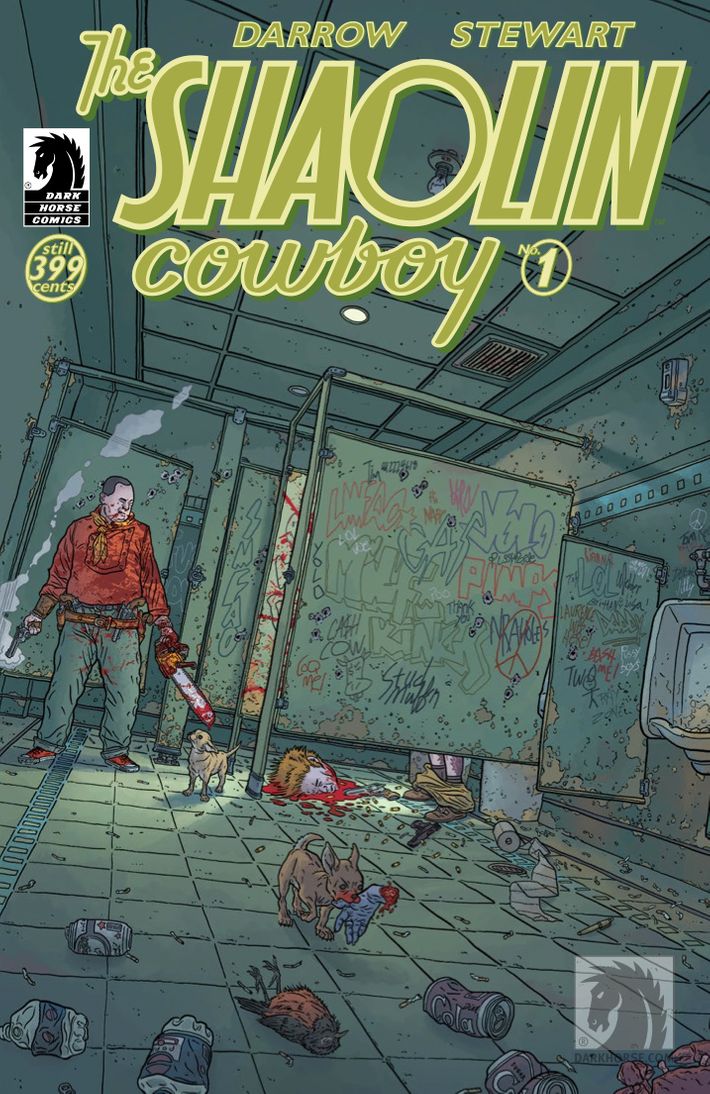

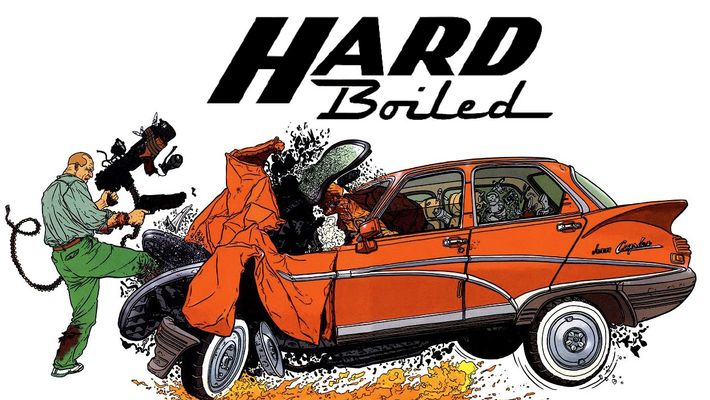

No one draws violence quite like Geof Darrow, and nothing he’s drawn is quite as violent as his latest graphic novel. The 59-year-old artist first became famous for 1990’s Hard Boiled, his insanely bloody collaboration with legendary comics writer Frank Miller, and since then has garnered acclaim for epic works like the monsters-and-robots tale The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot and the kung-fu/Western mash-up The Shaolin Cowboy — as well as his now-legendary concept art for The Matrix. But even die-hard fans couldn’t have anticipated just how insane Darrow’s newest offering would be.

The Shaolin Cowboy: Shemp Buffet is on shelves now, and I can safely say it has the best dialogue-free, 109-page zombie fight scene you’ll read all year. The novel, published by Dark Horse, follows the titular martial-arts master as he attacks a seemingly endless pack of zombies in the desert and — using his bare hands and a makeshift weapon comprised of a pole and two chainsaws — manages to defeat them all. It is, in its way, graceful and elegant, and all done with Darrow’s inimitable, hyperdetailed style. Don’t believe me? You can read the first chapter of the comic by clicking here now!

I caught up with Darrow to talk about Shemp Buffet, the agony of working on the Super Friends cartoon early in his career, his work on an aborted adaptation of the legendary manga Akira, and more.

How on Earth did you pitch Shemp Buffet? Did you have to explain why you wanted to draw more than 100 pages of dialogue-free zombie-fighting?

No, I just said, “This is what I wanna do,” and they said, “Okay,” and they saw when it was done and they printed it. They said, “Yeah, do what you want,” and I just did. They never questioned me, and I just did it.

Okay, but why do a 109-page fight scene?

I couldn’t tell you. I’ve tried to figure it out. I think it’s funny. I just wanted to see how long I could keep going before I got bored doing it. I don’t know, I think if I have to explain it, it kind of defeats the purpose of it. Also, I like Japanese comic books. As odd as it might seem, that happens quite often there. Sometimes even longer.

Click here to read the entire first chapter of The Shaolin Cowboy: Shemp Buffet.

How did you know you were done with the fight scene?

I got bored. [Laughs.] I thought it was time to wrap it up. I was gonna keep going, but I thought, What the hell are you doing?

How do you make each panel different in a fight scene? This is obviously the longest one I’ve seen you do, but you have extended fight scenes in a lot of your work. How do you keep it interesting from panel to panel?

You just try to find an interesting composition, and I think an interesting thing in this one is the sheer numbers and the idiocy of a guy with two chainsaws on the end of a long pole. Hell, I don’t know. Maybe it’s not interesting. It probably isn’t. But I kept trying to make it look good, I guess. Convincing in an odd, unreal kind of way.

A very nonviolent piece of your career is your time on the infamously bland 1970s DC Comics cartoon Super Friends. What was that like?

It was horrible. Hanna-Barbera had amazing artists working there, and they were all creatively castrated because they had standards and procedures. You couldn’t draw anything sharp or dangerous, and if you drew anyone that wasn’t white, they would have this group of white ladies that would be like, “Oh, he looks too black!” They couldn’t have guns, so basically what you would have to do is draw a square that a beam would come out of in a nonthreatening way. We were drawing a ship for something, and it was a war ship, it said it was a war ship, and they said, “Your drawing looks too warlike,” and I was like, “It’s called a war ship! What’s it supposed to look like? A daisy?”

You were like a line animator?

No, I was a character designer. We’d have to read these horrible scripts, and we would just sit there and laugh. I never thought I could fall asleep while reading at that point, but they were so boring and so bad that I would just start to nod off.

There’s a lot of stuff from the past of the superhero machine and industry that is fun and kitschy now, but yeah, Super Friends really doesn’t hold up.

One episode that sticks out in my mind was this one with a giant from space. You’ve got these astronomers looking through a telescope at the sun and suddenly the sun is blotted out. Cut to the universe, and there’s this giant — like, a medieval giant — and he strides through the universe collecting planets in his bag like they’re marbles. So he picks up the Earth and puts it in his bag and then Superman flies out and he has to get Earth out of the marble bag and put it back in its proper orbit. Of course, nothing happens on Earth. People aren’t even aware except, like, I think it’s dark that day. All these other planets somehow don’t bump each other. But Superman’s pushing the planet back out into space, Superman would be so tiny you couldn’t see him from space, but they turn him extra big so you can tell, so now he’s about five miles long. Nobody said, “This is just ridiculous.”

On to work that you’re actually proud of, let’s talk about your collaborations with Frank Miller. How in touch with Frank Miller are you these days?

I could get ahold of Barack Obama easier. Let’s put it that way. I try, I try, I try, and I don’t know. It’s just impossible.

Eesh.

I can tell you that Frank was incredibly generous with me because I drove him crazy. I was constantly going off on tangents because I didn’t know you weren’t supposed to change things [from the original script], so I was drawing stuff by saying, “Huh, that’s interesting!” He told me later, “You’d show me stuff and I’d come back and be like, ‘What are we going to do with that? You changed it!’” Anyway, once his movie stuff took over, it was really hard to get in touch with him.

Well, you’re still on good terms with the Wachowskis, right? Perhaps your most-seen work is all the visual stuff you conceived for The Matrix 16-odd years ago. At what stage in the process did you get involved with The Matrix, and what did the Wachowskis ask you to do?

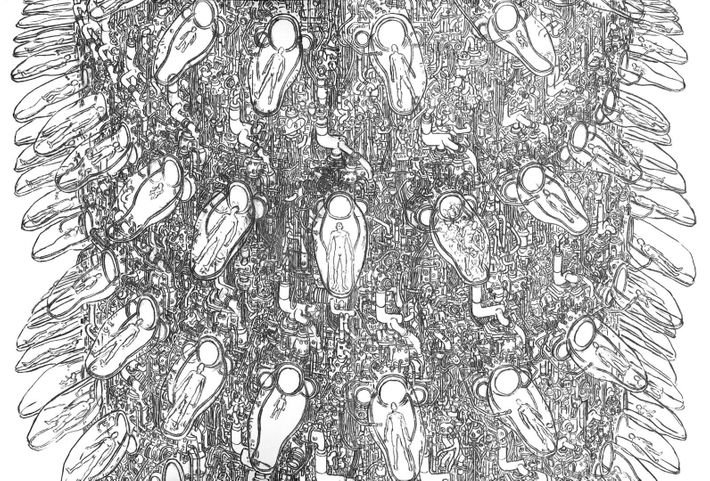

I was living in France and Warner Bros. called me up and said, “We’re going to make this science-fiction film with the Wachowskis,” and I had no idea who they were, and I said, “I don’t know who they are, I’m sorry.” They said it was this science-fiction thing, and I said, “Send me the script and I’ll read it and see if I think I can do it.” [The Wachowskis] told me later they thought that was so funny, because I was the only guy who asked to read it. The only reason I wanted to read it was not to see if it was worth my ability, but whether I could do it, because I wasn’t going to take a job if I didn’t think I could do it. And I read it and I was like, Wow, I sure would like to try! They flew me out to Hollywood to meet with them, and we hit it off, and the first thing they asked me to draw is what they called the “power plant,” those big columns with the bodies, the human lightbulbs plugged into these columns, and there are thousands of them on each one, like a Sequoia forest. I drew that and I sent it to them by fax, and they said it was even scarier than they’d imagined. They hired me for a few weeks at that point, and I did that and I worked on the chairs that [Neo and his allies] sit in, that they plug their brains into. A few months went by and they got money to where they could actually fly me in.

Did you work on Jupiter Ascending, the most recent Wachowski outing?

A little bit. A little bit, yeah.

What did you think of the finished product?

It was great! The only thing I can sort of look at and say, Well, that’s me, was the guns.

Last thing: I saw on your Facebook page that you mentioned doing some work on the failed live-action adaptation of Katsuhiro Otomo’s classic Japanese manga Akira. That thing has been stuck in development hell for decades and has gone through so many prospective directors. What was your involvement?

Oh, God. They called me up and wanted me to work on it. It was set in New York, and they said they were gonna make it better, because they talked about how it seemed a little outdated now. I think the thing still holds up so well! Oh, and they wanted me to redesign that iconic motorcycle, which I thought was crazy to begin with. It’s so iconic! In particular, it was a thing where they didn’t have a big enough budget, so they were trying to make it as relatively cheap as they could, so they made some deal with some motorcycle company. They’re gonna use that company’s motorcycle and just gear it up to kind of look like the Akira one. I’m not an engineer. I’m certainly not a car designer. I told them, “I’ll try.” I worked on it and I don’t think they liked it. I don’t know why you mess with something like that. I was kinda glad that it ended. I know Otomo a little bit, and the director [of the live-action adaptation] said, “I’d really like to meet him,” and I said to him, “I could probably get you in touch with him.” He said, “All I want is a real benediction,” and I said, “I doubt that’ll happen.” To have the audacity to think Otomo’s gonna go, “Oh, go ahead, great. You’re gonna make this better than I can!” The guy sweated blood to do that thing, and you’re gonna completely change it and you want him to lay his hands on you?

Which director was this? There have been a lot of people tied to that thing.

I’m not going to say! He saw my drawings, and I never heard from him again. First, he was calling me all the time, talking to me, talking to me, and then when he saw the drawings, he thought, This looks like shit, I guess. I got a call from the accountant, telling me they didn’t need any more production artwork. Classic Hollywood.