Kenny Schachter is a curator, writer, and collector based in London.

The megalith known as todayÔÇÖs art market has more personalities than noted 1970s schizophrenic Sybil. A recap of the hyped-up, rocket-fueled auction sales this past week might be better served in the form of an animated cartoon, but here is my attempt.

The trip didnÔÇÖt get off to an auspicious start upon my arrival from London ÔÇö I passed a prone man with police kneeling on his chest bang in the middle of Sixth Avenue, while he screamed at his accuser, ÔÇ£When I get out of jail I will have you killed.ÔÇØ

What a welcoming that might serve to reflect an art world characterized by the big guns ÔÇö megagalleries and auction houses ÔÇö tightening the reins on increasingly disenfranchised, mid-level artists and dealers.

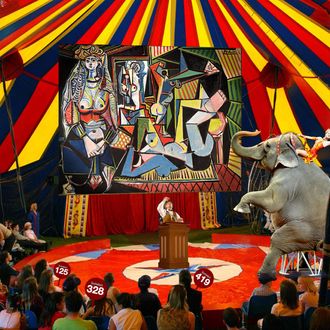

The auctions are like elections held in monster circus tents, where one and all anxiously await the results of the Lib Dems and Tories (Labour didnÔÇÖt rate a mention after performing so badly earlier this month in the U.K.). Objects are mercilessly traded and re-traded in a dizzying, tail-chasing cycle for ever-increasing profits. Can it or will it persist?

Sometimes the beanstalk seems to rise infinitely, while other times itÔÇÖs prematurely cut to size. Driving the art market in 2015 are the money-no-object global players so drenched in wealth that figures like $40, $50, or $100 million (or more) are shrugged off like a day at the races. And it can be as much of a crap shoot. Then there are the day-sale-trading In-N-Outers with attention spans like fleas (some with intelligence to match) and, believe it or not, people who still actually like art.

ItÔÇÖs a dangerous game for the unwary and seasoned pro alike. You only hear about the headline-grabbing office-building-scaled figures, but the everyday buying and selling of art is a minefield littered with multiple pitfalls and pratfalls; trust me, I stepped into it myself this time around (read on).

In an attempt to devour recently beleaguered SothebyÔÇÖs like a Freudian case study, ChristieÔÇÖs made the unprecedented move to cram its Impressionist, modern, and contemporary auctions into a single week, rather than spread over two. More unusual was the decision to compress art covering a span of 100 years into a standalone auction in addition to the regular evening sale of contemporary. Trying to sex up the diminishing stock and quality of Impressionist and modern art by co-mingling it with a hot stud called contemporary was like the silicone-enhanced but still ancient cougar leaving the bar of my hotel with her twentysomething paramour heading into the night, locked arm in arm. And it worked (for all I assume).

With so much on offer, ChristieÔÇÖs resembled a high-end flea market of rich people selling to rich people, with art seemingly busting out of broom closets on multiple floors. The tenor of the entire week was said to rest on the back of the success of a certain Picasso painting I canÔÇÖt force myself to mention (much). The Nahmad family allegedly guaranteed the work in question for $150 million, an astonishing amount much higher than previous perceptions on the street (like Wall Street, but more gilded), but less so in light of the fact there are additional works from the very series already in their free port coffers. Chairman and head of postwar and contemporary art Brett Gorvy audibly sighed as his face was overcome with placid relief after buying for his client the most expensive painting in history.

The art of auction house seating is a ruthlessly choreographed undertaking that would make Martha Stewart proud. Your (very) current status dictates positioning and can alternate between houses. ChristieÔÇÖs was generally Nahmad family front and center while at SothebyÔÇÖs the Mugrabis held pole position, an art world version of the Hatfield-McCoy feud.

When the big money hits, as it did regularly, the crowd breaks into applause for nothing other than the celebration of cash in and of itself, or recognition of the leap of faith one must take in order to believe art has intrinsic value.

On multiple occasions there was an entertaining dynamic between Larry Gagosian and clan leader Jose Mugrabi endlessly ribbing each other with competing bids, which elicited a Gogo groan at one stage. Beyond seating for mortals are the sky boxes, where itÔÇÖs a guessing game of fame trying to recognize celebrities by their silhouettes. ItÔÇÖs often not a particularly difficult task with the likes of a bearded and flat-capped Leonardo DiCaprio pressing his nose against the glass with a companion so slim she can only have been a model.

About the hats and caps of the rich and famous: One could have mistaken the boat atop a person I assumed to be Pharrell to be the headgear of the Canadian Mounties. I was later informed this was in fact Swizz Beatz. When an early, small Basquiat work on paper (no less) went over estimate at $13 million (estimate $9ÔÇô12 million) there was more whooping and high-fiving than at a party thrown by my 17-year-old. It seemed to mean that Swizz, husband of Alicia Keys, was the seller of the work and two-timing SothebyÔÇÖs in the process where he has brought in clients for ICÔÇÖs (introductory commissions). Basquiat is tattooed on SwizzÔÇÖs forearm.

With Drake having curated the music for an exhibit at SothebyÔÇÖs, for better or worse, we are deep in the midst of a Miley meta-moment of art and celeb.

Due to nagging hay fever, I sneezed from gavel to gavel at about every sale. Fumbling with my new iPhone at SothebyÔÇÖs evening sale (having recently parted with my beloved Blackberry), I lost a nightÔÇÖs worth of precious quotes when I had the absolute pleasure of sitting next to PaceÔÇÖs Marc Glimcher, who speaks in aphorisms, each more derisive than the next, other than for Pace represented artists and estates of course. (Those were all amazing deals.)

During the nightÔÇÖs proceedings the latest Mark Grotjahn achieved $6.5 million, a record for a painting that resembled CanadaÔÇÖs most recognized artist, Jean-Paul Riopelle, who died in 2002 at 89 (and happened to have lived with Joan Mitchell), whose auction record is just shy of $2.3 million. (Great gossip: A friend of the artist gifted a Grotjahn to another friend, who turned around and offered it for sale before it was finished. Call it a case of the gift that keeps on taking.)

Here are some additional random highlights that caught my eye (and wallet) over the course of the week, both day and night:

ÔÇó I have finally figured out the Fontana market, which has long eluded me, when a red number with 14 slashes went for $16,405,000 at ChristieÔÇÖs, amounting to $1,171,785.71 a cut. A Hirst butterfly on canvas from 2007 sold in the same place but in a day sale; ChristieÔÇÖs had many, also unprecedented, in their efforts to further cannibalize SothebyÔÇÖs, which went at the high estimate for $200k but still dramatically less than the $600,000 they originally sold for.

ÔÇó Best line overheard at an auction house: a collector quizzically looks at a specialist and says, ÔÇ£What do you mean when you say the artwork is critical?ÔÇØ To which the seasoned professional replied in a heartbeat: ÔÇ£Museums love it.ÔÇØ

ÔÇó Franz West, who has an auction record of $720,000 from back in 2008, made $329,000 at a ChristieÔÇÖs day sale with a papier-m├óch├® sculpture entitled Nipples while multiple works sold for upwards of $1 million at David ZwirnerÔÇÖs Frieze booth. The artistÔÇÖs market is deservedly in ascendancy ÔÇö and I say that not just because he happens to be in an exhibit I curated at TBD Gallery, open until June 14! (DonÔÇÖt miss it, please!)

ÔÇó Boston born, California-residing Jonas Wood, 38, is AmericaÔÇÖs answer to David Hockney ÔÇö who, incidentally, just said he hates Gerhard Richter in an interview for his show at LondonÔÇÖs Annely Juda Gallery). A Wood fetched a whopping $600,000 at SothebyÔÇÖs day sale, and after a successful outing at MoMAÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Forever NowÔÇØ painting show, Mary WeatherfordÔÇÖs first and only painting ever to appear at auction for sale fetched $237,500. She was born in 1963, so itÔÇÖs heartening to see deserving artists gain recognition well into their careers, and not have all the attention heaped upon the flash-and-burn hotties usually embraced by the flippers.

ÔÇó Cory Arcangel is only 36, but is considered the grandfather of internet art (now known as ÔÇ£post-internet ÔÇ£art for marketing purposes). He hit a record of $358,000 on an estimate of $40ÔÇô60,000, with his colorful, abstract computer-printed photos that could have been readily mistaken for the work of his cohorts Florian Maier-Aichen and Walead Beshty (also present in the sales).

ÔÇó New YorkÔÇôbased, Italian-born Rudolf Stingel (born in 1956) had one of the most breathtaking market moves, which ÔÇö along with the windfall enjoyed by Franz West ÔÇö was long overdue. Two works at ChristieÔÇÖs and Phillips respectively made successive records of over $4.7 million, each against his previous high of $2.6. A quantum leap, but he still looks cheap.

ÔÇó Oh, and regarding the comically inconsistent Phillips, I didnÔÇÖt mean to be mean when quoted in a New York Times auction coverage article about their ineffectiveness; I most certainly realize and appreciate what an important role they fill in relation to contemporary art (especially in making markets of emerging material) and they do seem to be growing, albeit at their own special pace of fits and starts.

Anatomy of a loss:

ItÔÇÖs no easy feat to be contrarian enough to actually suffer a deficit on the most coveted artist in the biggest bull market on record. That would be me. I discretionally bought a Richter and got whacked when it sold for less than the purchase price on a low estimate, a necessary evil of successfully enticing bidders without a guarantee. ThereÔÇÖs forever a plausible excuse for failure, a piece is either too big (or small), too often at auction, it has condition issues ÔÇö always another reason as to why not this time for this thing.

In consolation, I was in good company as three paintings did not sell by recent market high-flyer Tauba Auerbach, and though Christopher Wool famously caused a $30 million RIOT, his HYPOCRITE failed to get a single bid. The art market is a fickle beast, handle with care.

Though I am surely not the first to have come up snake eyes at the auction house craps table, the only thing more unusual than me admitting it was the offer I made to personally make up for the loss. I didnÔÇÖt commit hara-kiri but it was sobering enough.

Accounting for the overall stellar results of the season, $1 billion in a week by ChristieÔÇÖs alone is a world of frenzied art spec-u-lectors clotted with cash to an unprecedented extent; we all saw where a chunk of it went this week, but where could it all possibly have come from? ItÔÇÖs a dangerous game when you lose sight of buying art with the heart; it could be a very expensive proposition. Though money doesnÔÇÖt always equate to value in art (is this an anomaly or is there another sector this applies?) the market can be at least as good as any biennial curator.

The New York Times concluded its market coverage for the historic week by posing this cynical question: Despite the headlines, what is the financial truth? The truth is that more people across a wider swath than ever before like art enough to buy it (if not live with it). Many do not shy away from paying for what they believe to be the best. No matter what the vibe on the sales floors (there are many) the fact is the degree of interest is at a historic high, and not waning anytime soon. Thick in the air amid the good, bad, and really, really awful lies the unstoppable, implacable, genetically coded urge to create and collect. ItÔÇÖs great to be an inhabitant of a world prefaced by art.

But itÔÇÖs not all euphoria, far from it. As I said, there are many moods in this art market. Many personalities.

When I visited my friends at McKee Gallery, purveyors of Philip Guston and Vija Celmins, how I adore the gallery (and Guston), they thanked me for mentioning them in previous articles ÔÇö a line I donÔÇÖt hear much ÔÇö and we discussed their imminent closing, a sad day indeed. Their related statement said it all: ÔÇ£The art world has become a stressful, unhealthy place; its focus on fashion, brands, and economics robs it of the great art experience, of connoisseurship, and of trust.ÔÇØ That they are going pains me; losing such art-adoring passionistas, I will miss them dearly.