Longer than a New York City block and bigger around than a California redwood, the shark bursts skyward from a turquoise whirlpool, jaws gnashing, purple energy beams flying from its mouth.

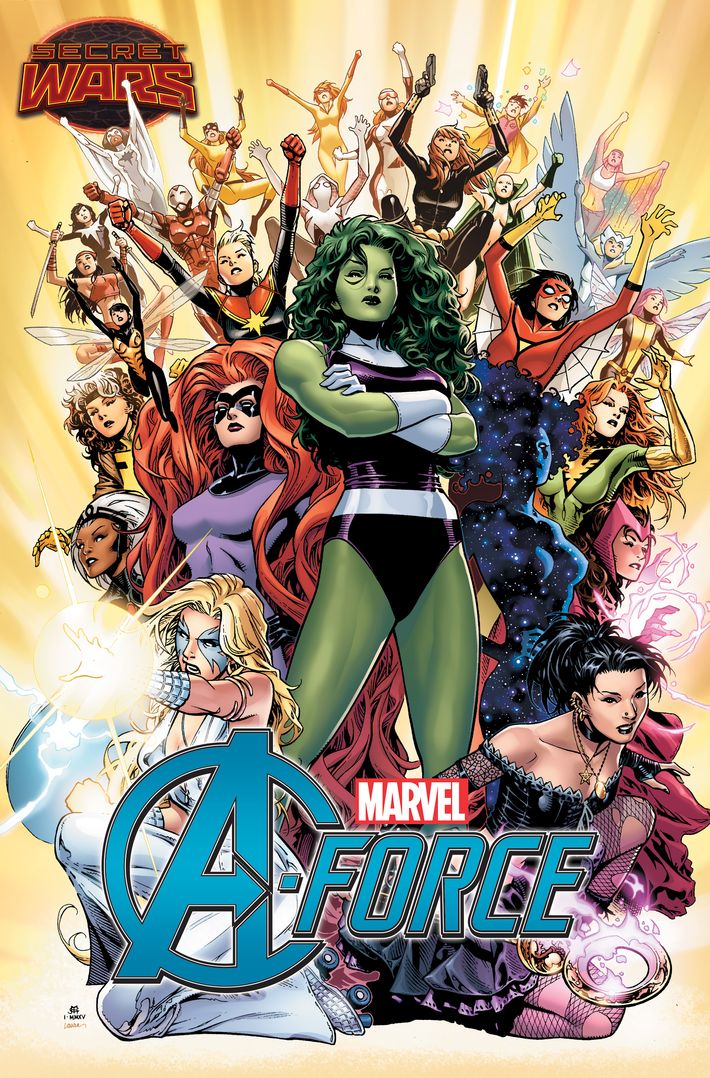

“It’s a Megalodon!” shouts Captain Marvel, alias Carol Danvers, a superhero imbued with superhuman strength, speed, and reflexes. She can fly and shoot photon blasts from her fingers, so when she wallops the huge, sharklike creature, it dives back underwater. Nico Minoru — a witchy Sister Grim — dives in after it, delivering her own purple blast, and then it’s Dazzler’s turn to deliver her deadly disco-light beams. Finally, Miss America hefts the thing and throws it into an otherworldly void. The Citizens of Arcadia are safe thanks to A-Force, Marvel’s first-ever all-women superhero team.

A-Force, a new series from Marvel, that debuted yesterday, features better-known characters such as Captain Marvel, Nico, Dazzler, Miss America, She-Hulk, Spider-Woman, and Storm, as well as more obscure heroes like Wasp, Namora, Mantis, Firestar, and echo. For a genre historically focused on male heroes, it’s an impressive pantheon.

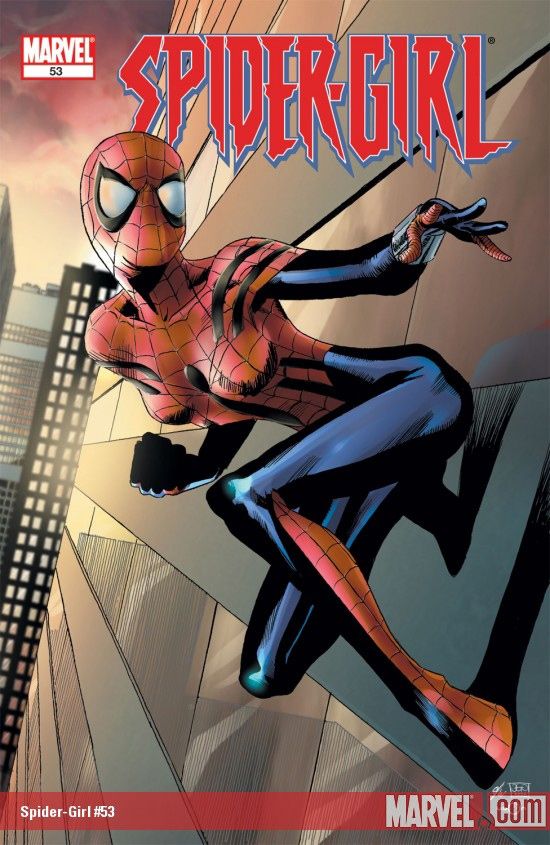

Promoting women-led series might seem like a novel move for Marvel, but it’s not. What’s novel is that they’re succeeding. Over the years, Marvel writers and editors have tried their hands at a number of series with female leads, but they rarely panned out, and in each case, the books were quietly canceled. One starring Peter Parker’s daughter, May, Tom DeFalco’s Spider-Girl launched in October of 1998 and, despite the protests of its fanbase, was canceled in 2010. X-23, which starred a mutant named Laura Kinney, ran for only about a year and a half — from September 2010 to March 2012. Although there have been other woman-led superhero series in Marvel’s past, they’ve been few and far between.

But now the women of Marvel are taking off in their own right. With female readership hovering at about 47 percent and women as the fastest-growing comics-reading demographic, Marvel is finally succeeding with a more diverse lineup of superheroes.

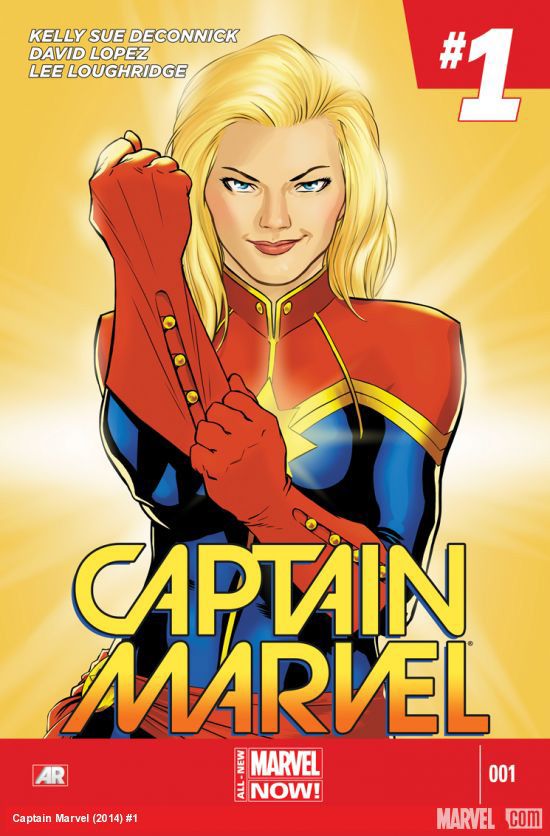

Spider-Gwen — a story set in a universe where Gwen Stacy, not Peter Parker, is bitten by a radioactive spider — is one of Marvel’s top sellers, with more than 250,000 copies of its first issue sold. Ms. Marvel, which launched just last year, is already one of the most successful books in Marvel’s lineup as well. Captain Marvel has one of the most dedicated fanbases in comics history. The new Thor features a woman in place of the hunky Hemsworthian Thunder God, and she’s outselling dude Thor by 30 percent. Silk, Black Widow, Gamora, Angela, and Spider-Woman are all female-led titles that Marvel’s launched in the past few years, and A-Force is another big step forward.

So what changed? Why are these new Marvel series succeeding where other series from the company failed? There are a few factors at work: the rise of digital comics, the growing power of female-dominated online fandom, and an increase in women creating comics.

***

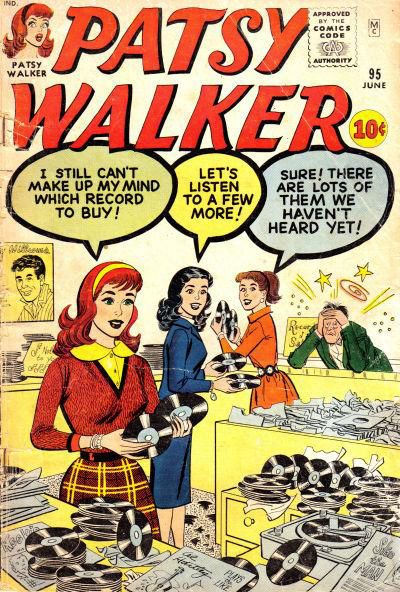

To trace the history of women in comics, you have to go back to the 1930s, when popular women’s magazines like Calling All Girls featured a hefty offering of comics. Even the initials for “Marvel Comics” first appeared in June 1961 on the cover of Patsy Walker, a lighthearted comic written by Ruth Atkinson that targeted women readers. “It is a myth that women are new to comics,” said Kelly Sue DeConnick, who writes Captain Marvel. “It is an out-and-out lie.”

From the 1930s to the 1950s, comics were sold at drugstores, in grocery-store checkout lines, and at gas stations; in short, they were much easier to find than they are today. But their “golden age” ended in 1954, when psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a book in which he argued that comics — specifically the romance, thriller, and mystery genres — were corrupting young readers. (It was recently discovered that Wertham faked a great deal of his research.) Wertham’s testimony led to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority, a self-censoring group formed by comics publishers, which closed countless publications and forced many of its boldest creators out of work.

This stigma meant comics were harder to find in public areas, and comics sellers earned a reputation (somewhat deserved) as seedy men in seedy, hard-to-find shops, hawking their collections out of cardboard boxes. Publishers emphasized superhero comics because they were among few genres not deemed “harmful” by Wertham. However, the superhero genre was dominated by male creators, and therefore male characters.

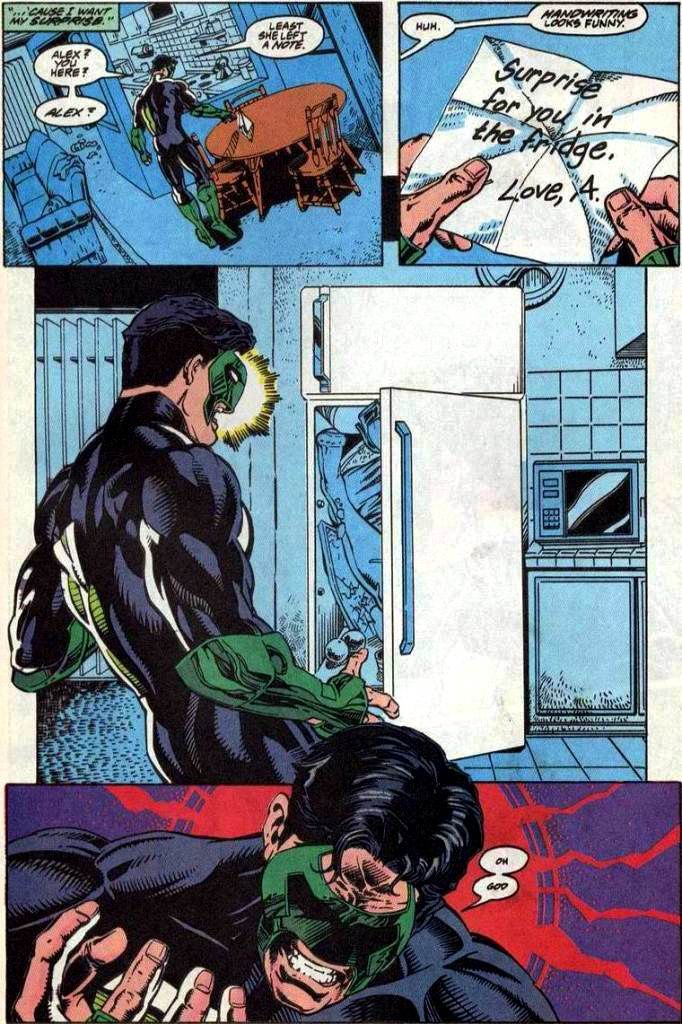

Even if women kept reading comics, the female characters to whom they might relate were largely one-dimensional love interests used to further a male hero’s story line. One particularly irritating trope became ubiquitous: female characters being maimed, raped, and mangled in service of a male character’s plot. In the 1990s, comics writer Gail Simone gave this phenomenon the term “women in refrigerators,” referencing a 1994 Green Lantern story in which Green Lantern comes home to find his girlfriend’s mutilated remains stuffed inside his fridge.

If they weren’t being stuffed into kitchen appliances, female characters were obsessed with shallow beauty and romance. Take the lead story in 1961’s Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane No. 27, which focused on beauty over brains — “The evolution ray that made me super-intelligent has turned me into a freak!” she moans, clutching her newly cone-shaped head. Even Carol Danvers — these days a tough feminist icon — was introduced in 1968 as a lovesick blonde swooning over a handsome alien superhero.

In the ’70s, Marvel gave Danvers — as well as She-Hulk, Spider-Woman, and Dazzler — their own series, but none lasted more than four years (compare that to, say, Uncanny X-Men, which has run uninterrupted since 1963). And they were the lucky ones: Characters like Black Widow, Rogue, Jubilee and Kitty Pride remained appendages of male-dominated teams. DeFalco’s Spider-Girl was a landmark for women in comics — it launched in 1998 and was the longest-running female-led series when it folded in 2006. Thanks in large part to a super-supportive fanbase, May Parker returned at the helm of Amazing Spider-Girl in October 2006, but that series folded in March 2009. DeFalco made a last-ditch attempt to keep May alive with Spectacular Spider-Girl, but that series only ran from July to February 2010, with Marvel pressuring DeFalco to wrap up May’s story in a single issue.

There was similar outcry when X-23 was canceled in 2011, particularly because it was Marvel’s only female-led series at the time. The series starred Laura Kinney, who turned out to be a Wolverine clone, and was written by a woman, Marjorie Liu. When X-23 was canceled, it was far from Marvel’s worst-performing book, which sparked outrage and speculation online about bias among Marvel’s editorial staff. Fans were pushing back, and they weren’t pleased.

***

The role female fans have played in this resurgence goes back to a key event at a DC panel during the 2011 San Diego Comic-Con. The panel boasted such heavy-hitters as Dan DiDio (co-publisher of DC Entertainment), Jim Lee (the other co-publisher of DC Entertainment), and Grant Morrison (superstar writer of series like Batman and The Invisibles), all there to promote their work. During the Q&A session, however, a woman dressed as Batgirl stood up and asked the creators point-blank why there weren’t any women on the panel. (Although DC is also making efforts to diversify with new series like Black Canary, Marvel is undoubtedly blazing the trail.) As news of the incident spread, blogs and fansites ignited, causing DC to issue a press release about fans’ call for “more women writers, artists and creators.”

“Batgirl was one of the first to bring attention to this in an extremely public forum, and both DC and Marvel had to take a step back and say, ‘Okay, what are we doing to foster this community?’” said G. Willow Wilson, who writes the wildly successful Ms. Marvel.

Fans wanted gender inclusivity on the page and on staff — but at that time, gender parity in comics-industry employment was at an all-time low. In July of 2011 (the same month as SDCC), DC released 86 new comics, but only 11 percent were credited to women creators. Marvel’s number was slightly lower: 90 new books, with 9 percent credited to women creators.

The lack of women behind the scenes gave fans even more incentive to fight for representation; they had concrete numbers to back them up. They wanted to see themselves in books, which meant they wanted more than flat, vapid female characters. They wanted real, complex women.

“The problem with the way many women in comics are written is they’re superficial,” said Ingrid Rios, who works at Manhattan’s Midtown Comics. “They’re about a woman, but they don’t have real insights as to what women experience.”

Rios and her co-worker Kayla Justiniano, another lifelong comics reader, agree the industry is slow and prone to missteps, but is changing. “You see it happening with [indie] books like Lumberjanes and Rat Queens,” Justiniano said. “Ms. Marvel is a perfect example; that book has something that’s the epitome of change.”

It’s striking how much Ms. Marvel’s protagonist, Kamala Khan, is unmistakably a 16-year-old girl. She’s grappling with newfound powers, but she’s also sneaking out to parties, fighting with her parents, writing fanfiction online, and getting grounded. And when she does discover her powers, she thinks it’s the coolest thing ever. “She’s not stoic,” Wilson said about the character, whom she co-created. “She’s not, ‘Yes, now I am part of this world and I carry this great burden,’ or whatever. She’s much closer to a fan.”

As Ms. Marvel grew in popularity, Wilson said fans began fending off online hate before it even touched her — like a private Kamala Khan army. Diverse characters such as Kamala and Carol Danvers (not to mention Miles Morales, Marvel’s half-black, half-Latino lead in Ultimate Spider-Man) seem to be tapping into an existing demand for diversity.

“Being diverse isn’t pandering,” Maggs explained. “Why is it that when you make a bunch of comics about white dudes, it’s not pandering to white dudes, it’s just normal, but when you make a comic about women, suddenly it’s pandering to women? It’s just making a comic about a woman the same way we’ve made comics about dudes for all this time.”

***

The huge success of Marvel’s superhero movies has also helped to prove the existence of a female comics audience. After the success of Iron Man in 2008, comic-book characters began to dominate the big screen in a big way. Disney bought Marvel in 2009, and its billions, combined with Marvel’s complex characters, made each subsequent movie a top-selling action flick. The films catapulted characters like Captain America, Thor, and Black Widow into the common pop-cultural lexicon in a way no comic book had before. Because slightly more women attend movies than men, Marvel’s films made superheroes even more widely accessible to female audiences.

There aren’t many reliable stats before 2013 that break audiences down by gender, but that year 58 percent of Iron Man 3’s audience was male, and 42 percent was female. Last year Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy was released — 59 percent of its audience was male, and 41 percent was female. Captain America: Winter Soldier (2014) drew a 58 percent male and 42 percent female crowd. Although the numbers are closer to 60-40 than 50-50, the fact remains that women watched superhero movies. Sure, some were familiar with Marvel’s pantheon, but some had never heard of female characters like Pepper Potts or Natasha Romanova or Jane Foster. Some connected with those characters and wanted to learn more, and those women joined the growing ranks of female comics readers.

“Because the gender audience breakdown in the big Marvel blockbuster film is surprisingly close to half and half, women are seeing the films and getting interested,” DeConnick said. “They’re thinking, Scarlet Johannsson as Black Widow was a badass; I might like to read a Scarlet Johannsson comic book, or Captain America is someone I aspire to be like; let me read more of his stories. As women are becoming interested, they’re returning to comic books.”

Marvel’s films popularized female characters just as digital comics became commonplace, removing a huge barrier to entry: the male-dominated comic-book shop. Now sites like Comixology allow users to choose from more than 200 million available downloads. Many publisher websites offer complete downloads of their own, with prices equivalent to those in stores.

As with most things (dating, ordering takeout, grocery shopping), buying comics online removes the friction associated with the process. As DeConnick put it, “You don’t have to find some store with cardboard boxes full of books and stinky dudes who don’t know how to talk to you.”

Over in a different part of the internet, Tumblr and Twitter have made it much easier for women artists and writers to share their work. “Now artists can put their comics up on Tumblr and get a huge following, and mainstream publishers will hire them,” said Sam Maggs, associate editor of progressive fan site The Mary Sue. “There are so many talented women out there that companies would be crazy not to go after them, and the more women we get behind the scenes, the more representation and diversity we’re going to see on the page.”

The same websites also give female readers a side door into an industry that many are discovering for the first time. “People on Tumblr and Twitter and Facebook are falling all over themselves to help you find the basic books that you need to get caught up on a character or start a story arc,” DeConnick said. Support from fellow readers makes the whole getting-into-comics process less intimidating.

Blogs like The Mary Sue, Women Write About Comics, Comic Book Resource, and Comics Beat have also had a hand in welcoming women back to comics. Online, women can talk about characters they love and discuss what’s happening in the industry at large. The Hawkeye Initiative replaces women on covers with male characters, just to highlight the ridiculous butt-and-boob poses to which the former are subjected. The Valkyries sprouted up to unite women working in comics shops across the country. The Carol Corps assembled on Tumblr. Once online communities began to rally female fans together, it was only a matter of time before publishers realized they existed in numbers large enough to sway the entire market.

“Now if someone makes a really sexist variant cover for Spider-Woman, everyone who knows what sexism is can say that directly to Marvel, directly to the creators, and directly to the publishers,” Maggs said. “And that’s hugely powerful.”

Maggs is referring to Marvel’s release of a controversial variant cover for Spider-Woman No. 1 last August, which showed Spider-Woman perched on the roof of a building posed, in the immortal words of 2 Live Crew, “face down, ass up.” The artist, Milo Manara, is famous for illustrating comic-book women in erotic positions. To fans, the real problem was that Marvel had commissioned him for the Spider-Woman cover in the first place.

A massive wave of internet backlash engulfed Marvel. “This does not instill confidence,” wrote Jill Pantozzi on The Mary Sue. “Nor does it tell women this is a comic they should consider spending money on. In fact, what the variant cover actually says is ‘Run away. Run far, far away and don’t ever come back.’” The company’s top editorial leadership publicly apologized and canceled the cover. As Marvel editor-in-chief Axel Alonso put it in an interview with Comic Book Resources, “we are aware of the growing sensitivity to covers like this, and we will be extra-vigilant in policing their content and how we use them in our marketing.” And there it was: Fanbase interacting with big-shot publisher. Readers who saw the cover for the blatantly sexist misstep it was making enough of an uproar that Marvel had to listen.

***

There’s one final ingredient in the explosion of female-led series at Marvel: vocal and popular female creators, as well as male creators who understand the need for change. DeConnick’s path to success at the company is particularly instructive. DeConnick pitched Captain Marvel to Marvel editor Steve Wacker, but even with his stamp of approval, she figured it was doomed. “I thought the book was going to get canceled in six issues,” said DeConnick. “I only planned six issues!” Spoiler: Captain Marvel is on issue 15 and counting, and Carol will soon be the first female superhero with her own Marvel film.

Like DeConnick, Wilson was less than confident when she started writing Ms. Marvel, the first-ever mainstream superhero series to star a teenage Muslim woman. “It used to be that a character like Kamala was the trifecta of death,” she said. “She’s a new character, new characters don’t sell; she’s a minority character, minority characters don’t sell; and she’s a female character, female characters don’t sell. So by the old industry math, Ms. Marvel should’ve shut its doors by issue seven.”

But that’s not the way things went for Wilson’s book. When Ms. Marvel was released in February 2014, it immediately topped Marvel’s sales charts, and the first issue even went into a sixth printing — a rare feat that only the likes of classics such as Batman and Spider-Man have ever accomplished.

Although Marvel is making strides, it still has a long way to go to achieve true parity. Of the 78 titles Marvel will release this month (one being A-Force), only six have a woman writer or illustrator working on them, and only two titles — Angela: Asgard’s Assassin #6 and Night Nurse #1, a one-off revival — have women writers and illustrators.

But although Marvel could use more women behind the pen, there’s a heartening trend of awareness among male writers at the company. Scribes like Jason Aaron and Jason Latour are penning complex, empowered women superheroes to spearhead their books. For Aaron, who switched from writing a male Thor in his Thor: God of Thunder series to a female Thor its continuation, it was completely natural that the next hero to wield the magical hammer should be a woman.

“Really, the only character that was discussed was Jane [Foster, a.k.a. Natalie Portman’s character in the movies],” he said in an interview with Vulture just after the new Thor’s secret identity was revealed last week. “It was me wanting to tell a specific story with this specific character. I was also very aware of the fact that, of all the characters we’ve seen pick up the hammer over the years, very few of them have been women.” (Although a number of female heroes have hefted Mjölnir over the years, the name “Thor” never transferred.)

“She’s grown and changed and evolved a lot over the years,” he said. “So this to me is not just the next step for her character, but really the next evolution of the core promise that has always been at the heart of Thor’s mythology.”

In other words, Aaron didn’t deliberately aim to please the female demographic by making Jane Thor. Instead, he chose a character who’s living her own struggle — an ongoing battle with breast cancer — because her story demonstrates the determination and fortitude that makes superheroes, men or women, super.