“In this world, there’s an invisible magic circle,” our heroine Anna, 12, tells us at the beginning of the new Japanese animated film When Marnie Was There, based on Joan G. Robinson’s 1967 children’s book. “There’s inside, and there’s outside.” Judging by the forlorn way she looks at her schoolmates playing among themselves, the lonely Anna, we suspect, is very much outside the circle. Or rather, she sees herself outside it: Though the film is sympathetic to her self-loathing, it also makes it clear that Anna’s feelings of persecution stem from within. A foster child who lost her biological parents at a young age, this girl seems forever to be poking away at an unhealable wound.

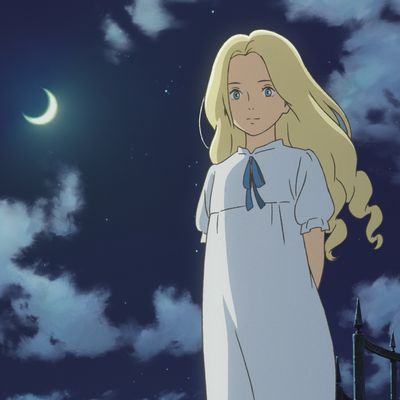

When Anna has an asthma attack, her foster parents send her to an aunt’s house by the seaside, where the air will be clearer. There, Anna finds herself drawn to a mysterious, sprawling, abandoned mansion (dubbed “the Marsh House”), which is reachable for her at low tide. But what’s this? In one window of the allegedly empty Marsh House, Anna sees Marnie, a beautiful blonde girl about her age. Like Anna, Marnie is lonely — neglected by her parents and occasionally terrorized by her maids. The two become the best of friends, but at first it’s hard to tell why, other than the fact that they’re drawn to each other — mystically, passionately, even dangerously. Whether Marnie exists in real life is also initially up for debate: For starters, she seems to belong to a past era, with her beautiful dresses and her elegant, old-fashioned surroundings. More important, Anna only ever seems to visit The Marsh House in a dreamlike state; their encounters usually end with her waking up in a field of grass or by the side of the road. Is this a figment of her imagination?

Initially, it’s hard to pin down exactly where the story is going. At times, it seems to take the form of a gothic mystery. (The film occasionally reminded me of Bernard Rose’s brilliant, seminal thriller Paperhouse.) Other times, it feels like a sensitive coming-of-age tale, as Anna’s anger over not having a biological family finds its correlative in Marnie’s sadness over her own distant parents. I even briefly wondered if the film might turn into a strange adolescent romance, given the fervor with which Anna and Marnie yearn for each other’s company.

But this type of clever uncertainty is also the stock in trade of Studio Ghibli, the animation company best known for the films of co-founder Hayao Miyazaki. This time out, the director is Hiromasa Yonebayashi, one of Miyazaki’s protégés (he also directed The Secret World of Arietty), and he’s learned his lessons well: When Marnie Was There, like many of the best Ghibli films, walks a fine line between simplicity and ambiguity. As the film dances around its emotions, we get the sense that it’s circling something it can’t quite bring itself to express. But this hesitancy rarely bothers us. Because, as we suspected, the film does have a game plan after all: It’s saving the emotional fireworks for the end. And that’s all I can say about that. When Marnie Was There may start off a bit awkwardly, but it’ll have you bathing in your own tears by the time it’s over.