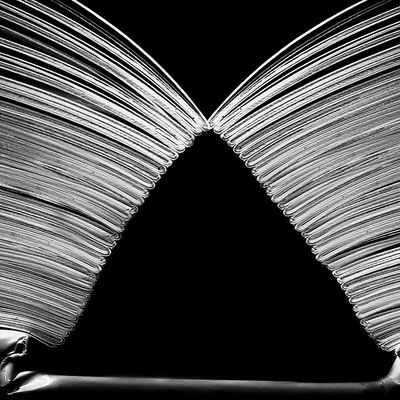

When Doubleday editor Gerald Howard acquired Hanya YanagiharaÔÇÖs A Little Life, a 736-page novel about a New Yorker with a hellish past, he told her theyÔÇÖd have to cut it down by a third. She countered that Eleanor CattonÔÇÖs The Luminaries and Donna TarttÔÇÖs The Goldfinch, both longer than her book, were poised to do pretty well that year. She also emailed a list of successful long novels, as well as a ÔÇ£passive-aggressive pictureÔÇØ of her manuscript beside a 900-page issue of Vogue and a paperback copy of Vikram SethÔÇÖs 1,400-page classic, A Suitable Boy.

Howard lost the fight, and Yanagihara turned out to be prescient. The Goldfinch went on to win the Pulitzer, and The Luminaries became, at 864 pages, the longest novel ever to win the Booker prize.┬á ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know if itÔÇÖs a real trend or just some statistical clutter,ÔÇØ says Howard, ÔÇ£but thereÔÇÖs definitely something going on.ÔÇØ

Like most ÔÇ£trendsÔÇØ in publishing, itÔÇÖs been going on more or less forever, with cyclical variations here and there. In fact, Garth Risk Hallberg, one of this yearÔÇÖs most notable high-page-count writers (whose 944-page novel, City on Fire, will be KnopfÔÇÖs most important literary debut next fall), wrote a story for the Millions way back in 2010 titled ÔÇ£Is Big Back?ÔÇØ Arguing that big booksÔÇÖ success complicates simplistic narratives about our collective ADD, he marshaled ample evidence, including Joshua CohenÔÇÖs Witz, Roberto Bola├▒oÔÇÖs 2666, and thousand-pagers by Jonathan Littell, Adam Levin, and David Foster Wallace that were widely read (or at least discussed). Perhaps Hallberg was just being savvy, laying the groundwork for the multi-million-dollar sale of another doorstop ÔÇö his own.

Nearly five years later, that list of megabooks is even longer. A Little Life has a rabid following and four printings so far; Larry Kramer just published The American People, an epic gay parallel history of the U.S. that runs to 800 pages (and thatÔÇÖs just Volume 1); Marlon JamesÔÇÖs sprawling Jamaican saga A Brief History of Seven Killings, out since October, is enjoying a run as long as the book itself. William VollmannÔÇÖs July novel, The Dying Grass, will close in on 1,400 pages, and Grove Atlantic just acquired a first novel called TheMystery.Doc, which is 1,700 manuscript pages long. Throw in several big-deal, massively popular series that are really single works split into volumes ÔÇö a small platoon led by Elena Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard ÔÇö and itÔÇÖs tempting to proclaim this the era of the Very Long Novel (VLN).

But again, maybe it was ever thus? ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt think the long novel ever went away,ÔÇØ says Jennifer Brehl, who edited Neal StephensonÔÇÖs forthcoming 880-page sci-fi story Seveneves. Other editors and agents of VLNs agree, but the notable thing about these books isnÔÇÖt that their heft is unprecedented; itÔÇÖs that all the forces Hallberg alluded to in 2010 are exponentially stronger today. We measure out our lives not just in tweets but in a blizzard of memes, Vines, Periscope soundings, and flash quizzes. We binge-watch, sure, but we wash dishes at the same time. Reading, on any device, is a discreet and solitary experience. ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre in a very noisy, fast-paced world thatÔÇÖs only getting noisier and faster,ÔÇØ says HallbergÔÇÖs agent, Chris Parris-Lamb, ÔÇ£and books, without changing at all, increasingly stand in relief.ÔÇØ

At least, thatÔÇÖs one of the ways that people pitching them try to sell us. The most popular explanation for the staying power of the VLN is no less true for its obviousness: counterprogramming. ÔÇ£The promise of a book remains a unique pleasure in contrast to thumbing through 800,000 Instagrams,ÔÇØ says Michael Pietsch, the CEO of Hachette and the editor of both The Goldfinch and WallaceÔÇÖs Infinite Jest. ÔÇ£The idea that one mind has created this world for you is a unique and perhaps even more compelling experience to us now.ÔÇØ

HallbergÔÇÖs essay called reading a VLN ÔÇ£an act of resistance.ÔÇØ It also dovetails with other fashionable affinities of the quasi-counterculture, from the fever for ÔÇ£longreadsÔÇØ to the cult of Etsy. ÔÇ£People seem to be seeking wholly immersive experiences,ÔÇØ says Knopf publicity director Paul Bogaards. ÔÇ£TheyÔÇÖre binge-watching, theyÔÇÖre cooking from scratch, going on ecotours. And thereÔÇÖs no more immersive experience than reading a good long book.ÔÇØ But ultimately, the cognitive dissonance of toggling between Snapchat and The Goldfinch requires no totalizing explanation. ÔÇ£The truth is that people live large, complex lives, and they want a multitude of experiences,ÔÇØ says Sam Nicholson, who edited Joshua CohenÔÇÖs The Book of Numbers, a slightly slimmer follow-up to the 800-page Witz.

But sometimes readers want a multitude of books, too. Along with apocalypses and superheroes, the book series is yet another genre convention bleeding into the lit mainstream. ÔÇ£It probably has something to do with that continued blurring of high and low, of what we consider highbrow and super-fancy and whatÔÇÖs just plain good storytelling,ÔÇØ says Farrar, Straus and GirouxÔÇÖs Sean McDonald, who handles KnausgaardÔÇÖs paperbacks and Jeff VanderMeerÔÇÖs Southern Reach trilogy. In a recent online column on the sudden popularity of the literary series, the novelist Alexander Chee invoked the parallel to binge-watching but also millennial obsessions like Harry Potter and science fiction. And he referred, interestingly, to ÔÇ£the world the writer has created.ÔÇØ World-building, a term once exclusive to physicists and game designers, is now on the tip of every book publicistÔÇÖs tongue. Asked what keywords they use in marketing VLNs, editors came up with variations on ÔÇ£creates a world.ÔÇØ Longer novels create bigger worlds.

Joshua Cohen once said that one of the eight publishers who rejected Witz told him theyÔÇÖd have published it at 200 pages. But the VLN editors and agents I spoke to (admittedly a self-selecting group) all claimed never to have turned down a book for being too long.┬á Most agents are impressed if they like a book past page five. ÔÇ£If I read the whole thing and itÔÇÖs longer than a few hundred pages,ÔÇØ says Anna Stein, YanagiharaÔÇÖs agent, ÔÇ£I canÔÇÖt imagine I wouldnÔÇÖt at least try to take it on.ÔÇØ

That doesnt mean its easy. VLNs are expensive to make  almost prohibitively so for translations  and must be priced higher at bookstores. (Vollmanns new novel will cost $55.) Its a good thing, then, that a books length can become a marketing asset. Knopf spent close to $2 million on City on Fire, so it needs a best seller no matter the page count. Advance readers copies arrived on media desks late last month, festooned with quotes from booksellers praising the novel for its most challenging quality. Even after 900 pages, I wanted it to go on and on, writes one. This is a vast deep ocean of a book  and reading it is no chore, writes another.

At publishersÔÇÖ sales conferences, buzzwords like important and┬áaudacious quickly give way to┬áimmersive and┬áaddictive. There are, too, the bragging rights earned by polishing off Middlemarch or its successors. ÔÇ£When [Little, Brown] brought out Infinite Jest,ÔÇØ Gerald Howard remembers, ÔÇ£they as much as presented the book as a challenge to readers. ÔÇÿAre you smart enough? Are you energetic enough to meet the Dave Wallace challenge?ÔÇÖÔÇØ

Published in 1996 at 1,079 pages, WallaceÔÇÖs magnum opus was both the bellwether of VLNs and a case study in how to sell them. Michael Pietsch remembers doctoring the margins to fit 600 words onto a page, double the average. Early copies went out on thinner paper ÔÇö the better to appeal to weary, sore-shouldered critics ÔÇö with a beautiful preliminary cover that telegraphed the rarity of the book in your hands. That rarity is what Parris-Lamb finds most appealing about a truly ambitious VLN. ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre all going to die before we read the worldÔÇÖs great literature,ÔÇØ he says, ÔÇ£but it would be feasible to read all the worldÔÇÖs great long novels.ÔÇØ

The flipside is that youÔÇÖre setting up some serious expectations. ÔÇ£If youÔÇÖre picking up a big book,ÔÇØ says Farrar, Straus and Giroux publisher Galassi, ÔÇ£youÔÇÖre competing with Tolstoy but youÔÇÖre also under the shadow of Tolstoy.ÔÇØ GalassiÔÇÖs next VLN, coming out in June, is an 816-page novel by Stephen Jarvis called Death and Mr. Pickwick. ItÔÇÖs a fictionalized account of the creation of DickensÔÇÖs first novel. The catalogue copy opens by calling it ÔÇ£a vast, richly imagined, Dickensian work.ÔÇØ