The New MuseumÔÇÖs tight two-floor, 27-work exhibition of Albert Oehlen gives ample evidence of the ways and whys this 61-year-old German artist is one of the most influential painters working anywhere todayÔÇöa virtual freedom machine. Oehlen is like a badger of painting, a cross between a weasel and a small bear, fearlessly scouring paintingÔÇÖs possibilities, implications, and metaprograms, scavenging for sweet spots, weaknesses, ways to decode, remap, and break down the mediumÔÇÖs programs, surfaces, image depiction, markmaking, and brushstrokes. I love his work, but I am not even sure that I actually like it. I hear the liberating bells it rings, and revel in them. And yet his work almost always has the look of being messy and structurally delirious, with so many visual and coloristic cross-references firing at once that they become soups of incredible pictorial gibberish. Like they come at me too hard.

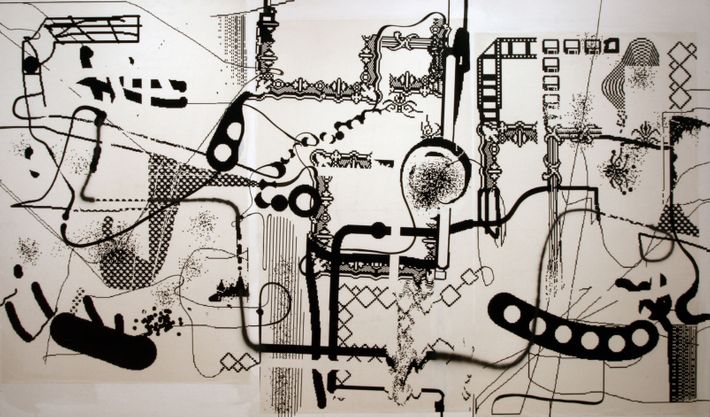

For the first eight years of his career, I think I thought of Oehlen as a strong second-string Kippenberger, Schnabel, Markus L├╝pertz, or Polke type of painter ÔÇö German, punkish, trashy, brash, tearing up painting in carnivorous ways. That was in the early 1980s, and I found him good and smart but not up to first-level ambition or admiration. I donÔÇÖt think I thought about him again until the mid-1990s. Then he threw me for a real loop. His early work had been large, splashy mash-ups of figures, household objects, and abstract shapes in marshy fields of muddy color. Then, almost out of nowhere, and probably before anyone of his generation, in 1992, he began probing the significant surfaces and possibilities of digital imagery and the tools that make it. Employing a Texas Instruments computer and picture programs, along with spray-paint, silk screen, collage, and bushstrokes, utilizing mainly black and white ÔÇö colors that are more ideas than real, as they donÔÇÖt actually exist in nature ÔÇö he suddenly developed a subspecies of painting all his own. So many other artists have now followed in his footsteps that it may be hard for viewers to grasp just how shocking this work looked at the time. At least it was for me.

When you get to the section of the show containing these, youÔÇÖre seeing Oehlen finding something in paintingÔÇÖs inherent program, something that must have been there from the beginning ÔÇö another level of abstract possibilities and endless processes, a way to almost paint against paintingÔÇÖs program, rather than making the medium adapt and absorb human needs. This opened 10,000 doors, to as many artists. Pause here to give Oehlen props ÔÇö even if the works strike you as stark, too stripped-down, lazy, or the beginning of too many subsequent bad careers to name. Oehlen found a way to embed electromagnetic information into the spaces, surfaces, and materials of painting.

They struck me that way, too. As when I had relegated him to the second tier in the ÔÇÿ80s, in the mid-1990s, I saw these black-and-white works as too easy, thought the surfaces looked slapped together, and couldnÔÇÖt process that lines were being made with a new device called a ÔÇ£mouseÔÇØ and then transferred into coded files and reproduced onto the canvas. (Almost the exact resistances we see today to artists like Wade Guyton and Richard Prince.) I had no problem with an artist not touching his work ÔÇö this was nearly 100 years on from Duchamp, and 30 years after Warhol. And yet I failed to see that Oehlen had bypassed then-fashionable critique theory and deconstructions of painting. Instead he was voraciously badgering the mediumÔÇÖs carcass, transforming, reevaluating, seeing that paintingÔÇÖs deepest structures contained the possibilities of adaptation, mutation, and growth while also redefining skill and beauty and maybe tools. The ways he was doing all that even now look radical and magical, like maps to other kinds of thinking, graphic worlds, and chains of non-symbolic meaning.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Oehlen also created large, allover abstract fields of reproduced images, pictures that looked swollen from bee stings, out of focus, about to erupt into visual nothingness. His colors became highly keyed-up, acidic, hazes of pink, purple, magenta. With little annoying bad-boy nihilism, these works seemed to take old-school Abstract Expressionism, Rauschenberg, and Rosenquist on pop-punk joyrides, all the while maintaining graphic-pictorial integrity and control. Again, IÔÇÖm not even sure I actually like these paintings. Yet I see them as real signposts pointing in so many directions simultaneously that I see these canvases as compasses to wherever I allow them to take me.

For this, the curators of this show deserve a lot of credit. Not only because the New Museum has one of the worst spaces for exhibitions, but because rather than laying out a building-filling survey of an art star, they have chosen to give us two or three of these highly unstable crucial oscillation points in OehlenÔÇÖs career. The result is that you see through mastery and market thoughts, and glimpse an artist whose energy is hot like de KooningÔÇÖs but whose work is endlessly ironic, posed, utilizing ideas that others and probably he dismissed as useless, silly, stupid. ThatÔÇÖs what I meant by calling Oehlen a ÔÇ£freedom machine.ÔÇØ WeÔÇÖre not just seeing silk screening, computer graphics, color, images, and the like; the deep content of this work is flexibility, openness, the willingness to abandon everything to see how much more the vessel of painting and even the self might hold, while at the same time making it all look as easy and sometimes as ugly as pie. Oehlen reminds us that first and foremost, all artists are or should be technicians of freedom that set other people loose.