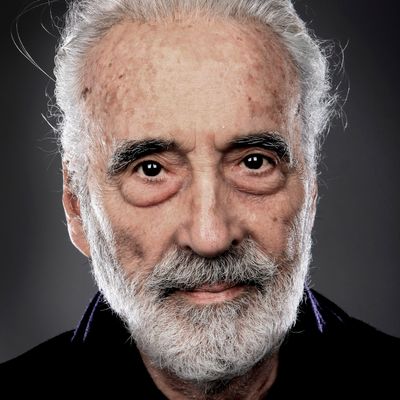

Christopher Lee ÔÇö Sir Christopher in his final years ÔÇö was the last living horror icon in the mode of Lon Chaney Sr., Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Vincent Price, and LeeÔÇÖs frequent co-star, Peter Cushing, and it was an association with which he only reluctantly made his peace.

His Count Dracula in the 1958 Horror of Dracula (British title: Dracula) remains an indelible portrait, alternately totemlike and bestial, with a penchant for nuzzling his buxom female victims before savagely sinking his fangs into their throats, and it made him an international star ÔÇö but in the sorts of films he always longed to escape. In interviews, he took every opportunity to quote artists on his versatility, among them Billy Wilder (for whom he appeared as Mycroft in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes) and his The Lord of the Rings antagonist Sir Ian McKellen, who reportedly said that LeeÔÇÖs avoidance of the stage had robbed the Shakespearean theater of a great voice. In 2002, he told me, crisply, stabbing a long finger for emphasis, ÔÇ£My whole life has been about proving people wrong.ÔÇØ

Why was he so touchy about what is, by any measure, a remarkable legacy? It went back ┬áÔÇöas most things do ÔÇö to his childhood. Born Christopher Frank Carandini Lee in LondonÔÇÖs upscale Belgravia, he lived a privileged life until he was 13, when his stepfather went bankrupt. From his Italian mother he got his dark complexion, and his outsider status was cemented when he shot up to six-foot-five. After a stint in the Royal Air Force, Lee decided to become an actor but was told by casting directors he was ÔÇ£too tall and foreign-lookingÔÇØ to play proper Englishmen. So he played Nazis, Arabs, Spanish pirates, Asian torturers, and, in 1957, the monster to CushingÔÇÖs Baron Frankenstein in Hammer FilmsÔÇÖ Curse of Frankenstein, the film that kicked off the British horror boom that lasted until the mid-ÔÇÖ70s.

So Lee ÔÇö despite being an English menÔÇÖs-club type to the core (en route to his tailor in London, he boasted to me that heÔÇÖd never heard the Rolling Stones) ÔÇö would spend nearly seven decades embodying the ÔÇ£alien other.ÔÇØ He was famously mortified when, in the late ÔÇÖ60s, a delegation of titled officials arrived at Pinewood Studios to bestow on Hammer a royal proclamation ÔÇöa nd the first thing their eyes beheld was Lee writhing on a giant cross, gnashing his fangs and weeping tears of blood.

That was in Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, one of seven Hammer Dracula films he disdained ÔÇö despite the fervor of adolescent horror geeks like me who could tell you how the Count met his end in each of them (sunlight, running water, giant crucifix through the heart, nervous breakdown in a re-consecrated church, lightning strike, wheel spoke and stake through the heart, hawthorn branches plus stake). Lee died in most of his 200-plus movies, and it was always an event. Coldly imperious onscreen, he was never so animated ÔÇö nor so poetically vulnerable ÔÇö as when attempting to extricate himself from a stake or sword or shaft of sunlight.

Working in generally low-budget fare, Lee played vampires, mummies, warlocks, Mr. Hyde, Fu Manchu, and the occasional sexual sadist. A lot of the films, he said, he never watched. (Lee signed Jonathan RigbyÔÇÖs eloquent, dauntingly thorough retrospective book, Christopher Lee: The Authorized Screen History, ÔÇ£You have my gratitude and my sympathy.ÔÇØ) He could seem stiff in repose, but in motion he had a pantomimistÔÇÖs fluidity, and his cavernous voice made even his lamest dialogue resound. Lee was famous for eliminating a lot of his lines as Dracula, explaining it would be better to say nothing than what the writers had written and insisting that he always tried to show, in his eyes, ÔÇ£the loneliness of evil.ÔÇØ

With the right material, he was brilliant: As the assassin Rochefort in The Three (and Four) Musketeers, the hearty pagan lord in The Wicker Man, and the cheerfully urbane psychopath Scaramonga in the (otherwise lousy) Bond picture┬áThe Man With the Golden Gun. Hoping for a more mainstream presence, Lee moved to Los Angeles in the late ÔÇÖ70s, but apart from a small role in Steven SpielbergÔÇÖs 1941 and a memorable hosting gig on Saturday Night Live, few of his American projects (among them Airport ÔÇÖ77, Serial, and Police Academy 5) did much for his reputation. He was eyeing a different sort of career when he turned down the role of Dr. Loomis (ultimately played by Donald Pleasance) in John CarpenterÔÇÖs Halloween.

Ironically, what changed LeeÔÇÖs fortunes was a generation of Hammer fans who grew up to be big-deal directors and started casting him in their movies. Joe Dante got the ball rolling with the rollicking Gremlins 2 and then Tim Burton cast him as a magistrate in Sleepy Hollow, a clear homage to Hammer. For Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, the second movie of the second Star Wars cycle, George Lucas wished aloud for another Peter Cushing type. (Cushing had played the Grand Moff Tarkin in the original Star Wars.) Was it a coincidence that Lucas named LeeÔÇÖs Jedi turncoat Count Dooku?) Most important of all to Lee ÔÇö a lifelong Tolkien buff ÔÇö was getting to hurl mighty imprecations to his foul Middle-Earth minions as the towering Saruman the White in Peter JacksonÔÇÖs The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

Lee had a reputation for being proud and humorless, and he certainly wasnÔÇÖt easy. But everyone IÔÇÖve met who knew him well adored him, insisting that once you got past the prickliness, he was kind, loyal, and immensely endearing ÔÇöone of the true good guys. And his personal life was enviably stable. He was married to his wife, Birgit, for 54 years, and was by all accounts a doting father to their daughter.

The day before his 80th birthday, Lee ÔÇö remarkably hale despite a bad fall a few months earlier ÔÇö told me he wasnÔÇÖt certain he had much time left but that heÔÇÖd endeavor to remain alive until the release of Star Wars Episode III. That would come in 2005. In the bonus decade, he joined Mick Jagger as a Knight of the Realm, though I have no idea if he ever gave the Rolling Stones a listen. He did, in his 90s, release an album of heavy-metal covers, which suggested heÔÇÖd loosened up quite a bit. Perhaps the title made that easier. I hope he knew he had nothing left to prove.