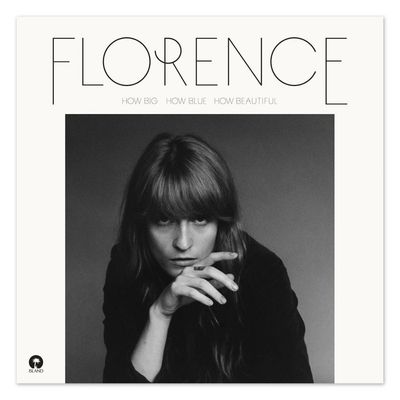

In the early stages of writing her third album, How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful, Florence Welch brought her producer, Markus Dravs, a demo of a song she had titled “Which Witch.” She was envisioning a high-flown concept album “about a witch that goes on trial for murder in Hollywood,” she recently told the L.A. Times, “like The Crucible: The Musical.” A lover of all things sweeping, macabre, and vaguely otherwordly — not to mention music’s biggest champion of the bell sleeve since Stevie Nicks — Welch had initially tapped Dravs to produce the record because she wanted a collaborator who would call her on her own clichés and push her out of her comfort zone. And if you are Florence Welch, the bull’s-eye center of your comfort zone is a song called “Which Witch.” Which means that the advice Dravs gave her was very appropriate: “No, no — you can’t do that.”

The flame-haired, 28-year-old Welch occupies a strange in-between place in the pop landscape right now: She’s an almost-A-lister who still somehow feels a little underappreciated (at least in America). She’s responsible for, in my mind, two of the best pop singles of the past decade — the spiky, harp-gilded “Dog Days Are Over” and the cathartic, Gilded Age soul of “Shake It Off” — but her highest-charting moment in the States has been her somewhat faceless feature on Calvin Harris’s club hit “Sweet Nothing.” When trying to convince people of her merits, I’ve sometimes wondered if Welch’s overblown, easy-to-pigeonhole aesthetic unfairly undersells her talents. She’s the sort of female artist who too often gets dismissed as “ethereal” or a “chanteuse” (two of the most cringe-inducing words in the Music Critic’s Dictionary; BAN THEM) — but listen more closely to her records and you’ll find a presence much more muscular, earthy, and violent than those placating epithets suggest. She’s a powerhouse; Welch’s lung capacity could give the Big Bad Wolf an inferiority complex. On her very good 2009 debut album Lungs — a dizzying mélange of orchestral pop, vampy soul, and unvarnished garage rock — Welch was part-goddess, part-pub-stool-regular, always one breath away from instigating a bar fight of cosmic, mythological proportions. Her follow-up, 2011’s pearly Ceremonials, took place on an even grander scale: Tracks like “What the Water Gave Me” and “Never Let Me Go” played out like love songs sung to the ocean and the sky, as if they were Welch’s logical peers. Ceremonials, though, was all crescendo, and it suffered a bit for it — over the span of an entire record, the gust of it all became a little exhausting and same-y. Welch barely gave herself a moment to catch her own breath. Though its title seems to hint at a similar kind of grandiosity, How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful is actually an attempt to scale back Welch’s more dramatic impulses and explore some unfamiliar lyrical ground. Which meant those odes to the sea were the first to go. “[Dravs] had a pint glass for me in the studio,” she told Zane Lowe recently. “It had a label on it that said, Water to drink from, not write about.”

At times, this newfound simplicity and groundedness allows for Welch’s vocals and knack for pop craftsmanship to shine brighter than ever. The great lead-off single “Ship to Wreck” (yep, she still managed to sneak in some nautical imagery; old habits die hard) is a darkly glittering slice of pop melancholy — basically one of the best Cure songs Robert Smith never wrote. (Don’t let the ginger tresses fool you; Welch is one of music’s last great goths.) The sparse, soulful “Delilah” is another highlight, and another foray into minimalism. Piano chords ring out unhurriedly; where there might have once been harps and timpani drums and all manners of baubles, Welch now fills the blank spaces with confident silence. (Fittingly, it’s a song about the slow healing of a broken heart: “I’m gonna be free and I’m gonna be fine,” she sings, before the backing singers butt in with some real talk, “Maybe not tonight.”) Nowhere do these progressions come together more powerfully than on the haunting kiss-off “What Kind of Man,” a punky, confrontationally passionate ode to an impassionate lover. Welch begins the song in a low, wounded croak, and it gradually builds in intensity until she’s suddenly caught in a reverie, flinging off the hurt like a whirling dervish. The best Florence songs feel like this, a little wild and a little private, like a pagan post-breakup ritual you’ve accidentally stumbled upon while getting lost in the woods. “What Kind of Man” earns its place among them.

I only wish the rest of the album hit so hard. How Big, How Blue loses its power supply about halfway through and moves through a snoozy middle section that begins with an aimless, formless ballad called “Various Storms and Saints” (I’m sure Dravs had her put another quarter in the water jar for that one) and ends with the prim lite-rocker “Caught,” which sounds like something Adele rejected from her perennially forthcoming album. While it’s nice to hear Welch sound a little more restrained, backed by little other than electric guitars and understated strings, I have to admit these songs make me miss the harps and the baubles and the drama; I’d almost prefer More Songs About Witches and Water. Luckily, Welch gets it back in the end with the sprightly, transcendent “Third Eye,” a song that all but screams, “Remember when I opened for U2?” Like pretty much every song a white person has ever sung about her “third eye,” it teeters on the edge of corny, but it’s got one of those classic Florence crescendos in which it’s almost impossible not to get swept up. “I’m the same, I’m the same, I’m trying to change!” she hollers, the hard-won labor evident in every acrobatic breath.

At this year’s Coachella, Welch concluded her performance by leaping off the stage and breaking her foot. In subsequent performances to promote the new record, she’s been confined to a stool. When I saw her play some of the new songs in Brooklyn last month, she was poised but radiated a certain restlessness; when she recently played “What Kind of Man” on SNL (far and away one of the season’s best performances), she trembled with caged intensity. You don’t get the sense that the injury will turn her cautious — somewhere behind her eyes you can almost see her plotting further feats of daring. Which is pretty much how I hope this transitional-seeming record will look in retrospect. “Maybe I’ve always been more comfortable in chaos,” she sighs on “St. Jude,” a pretty but placid ballad that fails to build to much of anything. It’s a moment of self-acceptance that, if we’re lucky, portends stormier waters ahead.