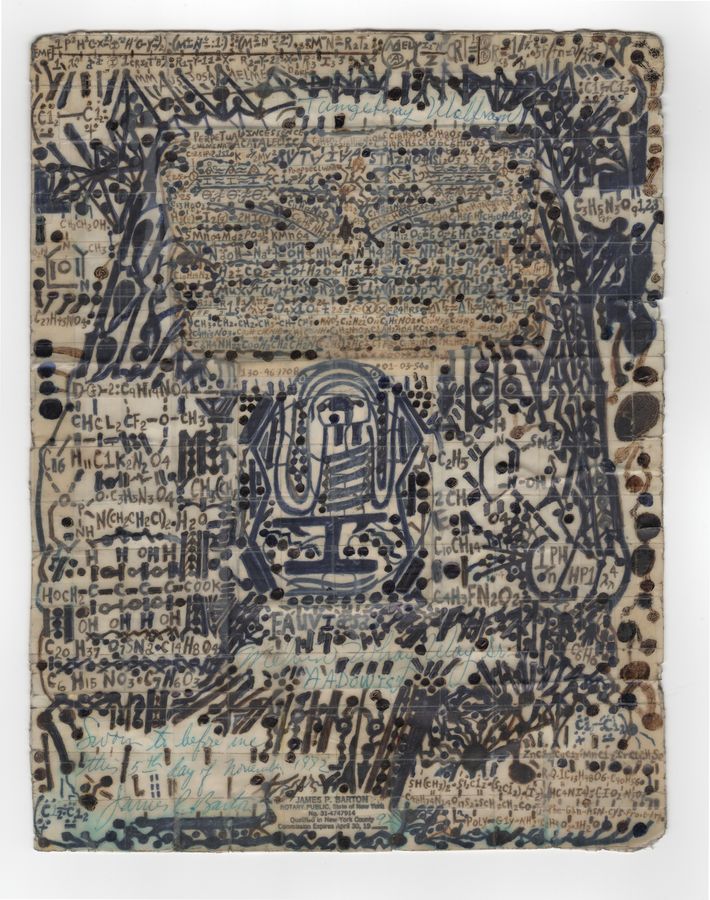

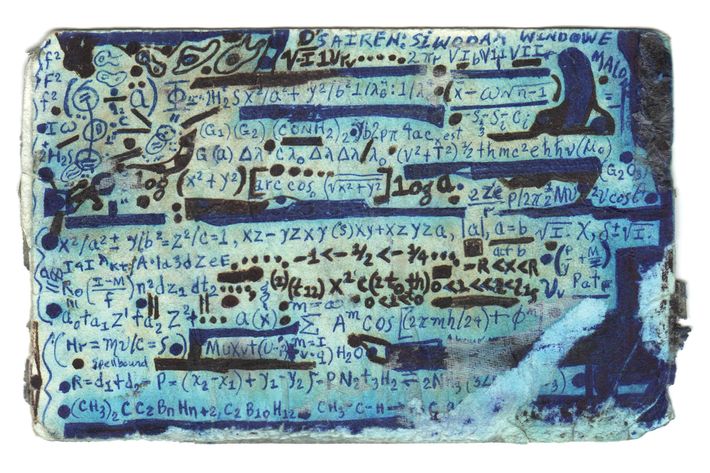

One of the best exhibitions IÔÇÖve seen this year consists of 34 intense ballpoint pen drawings on cut-up and folded paper crisscrossed with foggy layers of Scotch tape. None of the drawings is bigger than a Bible, all have been made in the last 20 years, and some are hard to see because theyÔÇÖre so jammed-up with optical information. Some look like theyÔÇÖre written in Greek, Aramaic, or other tongues. At least three are masterpieces.

Melvin WayÔÇÖs work isnÔÇÖt well-known, and it is far from easy. Even I get put off, daunted. Typically, he produces retinally dense, hermetic spaghettis of messages in thick visual giblets and graphic entanglements on resin-y surfaces ÔÇö everything is knotted, almost emulsified, accreted clusters of equations, signs, numbers, coded formulas, and dots. This is the intertwisted world of Melvin Way ÔÇö now the subject of a large-scale show, his first anywhere. I fancy the exhibition, on view through July 19 and Christian Berst Art Brut, will be the beginning of WayÔÇÖs deserved entry into the canon of 20th- and 21st-century visionary art.

Way was born in Ruffin, South Carolina, in 1954, and went back and forth between there, where he was raised by a parental figure named Flossy, and Brooklyn, where he stayed with relatives. An adept student who studied science, played music, and sang, he eventually went to the R.C.A. Technical School in midtown Manhattan, then worked as a machinist, living with a girlfriend who had drug problems before he developed schizophrenia in his early 20s. Since then, heÔÇÖs spent his life in and out of state-run mental institutions, homeless shelters, halfway houses, drug rehabs, and correctional units. He claims to have once roomed with Thelonious Monk. He should have fallen through the cracks. He should be dead. (In fact, he had a heart attack the night before his opening. He is now recovering in South Carolina with Flossy.) We owe his being discovered at all, saved, and brought to public light to the capable artist Andrew Castrucci, who discovered Way in 1989, when he was conducting art workshops in Keener MenÔÇÖs Shelter, a hospital-cum-prison for the mentally ill on Wards Island. Seeing genius immediately, Castrucci devoted himself to Way ÔÇö working with him, helping him in and out of institutions while the artist would sometimes disappear for long stretches, going on benders, turning up in emergency rooms or drug rehabs, other times arriving at CastrucciÔÇÖs door with as many as 200 or 300 rumpled new drawings. Castrucci introduced Way to tidal charts, hermetic diagrams, medieval cosmographies, navigation maps, and Post-Impressionism, another art made up of an infinite number of marks. He introduced him to da VinciÔÇÖs notebooks and backwards writing, which Way claims to have decoded and interpreted. And Castrucci has always passed earnings from sales onto Way.

IÔÇÖve been following Way since the early 1990s, when I was smitten by a small group of Ways shown in an outsider art fair in the basement of Cooper Union, in a wee nook presented by the pioneering Margaret Bodell, who was aligned with Hospital Audiences Incorporated, the indispensable organization helping disabled artists. (I bought one of WayÔÇÖs drawings there; IÔÇÖm told Artforum┬áco-publisher Knight Landesman bought another.) She soon led me to Castrucci. I went to his squat near Avenue D, where he helped run an artist-operated space. There I had a conversion experience. In a small, unheated room in winter, Castrucci pulled out from under the bed a battered chest of WayÔÇÖs drawings and spread them on the mattress. I felt like I was seeing another kind of infinity, thought made visible, wild nerves, optical barnacles coming to hermetic life, delirium legible. Some years later, Castrucci introduced me to Way, an African-American with stark pale blue eyes. I listened, gripped, as he spoke. I believed we were speaking to one another; soon I realized he was speaking to me from a dimension where I understood all the words but none of the meaning. I was thunderstruck ÔÇö afraid the way one is around the mentally disabled, and in the manner of when one is in the presence of a mighty spirit and a powerful being. Usually we run from fear, but I knew mine was meaningful. I thought Way was mad, but Hamlet mad. There was tangible grandeur in what he was saying, like he was dissecting and reweaving what we were talking about from the inside. I felt like a Romantic anachronism, projecting wisdom onto the troubled, but everything he was saying astonished me: truth, but told with another kind of Emily Dickinson ÔÇ£slant.ÔÇØ

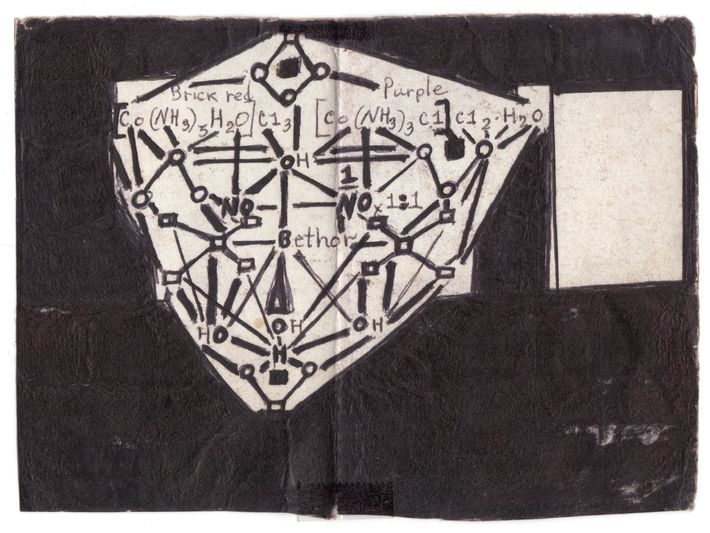

Examine these tidal swarms and chaos, and they can come into strange focus. If you can get past the snarls, graphic sameness (even I never really know if IÔÇÖve seen one before or not), and lack of color in WayÔÇÖs work, look closely at his repeated signs, words, punctuation marks, scribbling, and phrases. See his alphabet soup and optical algorithms, this gibberish from some mystic scriptorium ÔÇö compact knots of letters, lines, and initials, numbers in strange sequences, weird, mathematical-like notations, drawings of cells, Venn diagrams, an insignia for KOOL cigarettes, thickets of pictures. Together they are another beauty in themselves.

Until now, however, IÔÇÖve only seen and pleasured in the surface of his work, its formal and psychic frission, his stuttering, clutched touch, collaged and curled surfaces, hues of hazy light, cryptologies, numerologies, and two-dimensional cabinets of curiosity. I never thought to look up any of these signs, symbols, maps, numbers, or initials. But last week I went home and did that, and the thunderstruck feeling came back at once. More often than not, the things Way is referring to are natural facts of one kind or another ÔÇö biological, genetic, chemical, natural, mathematical, cosmological. In his work, you see him creating synaptic connections between real things in possible and impossible ways, all with great graphic imagination.

A lot of what Way portrays is derived from chemical notation; patterns of growth; chemical signatures for hydrogen bromide, ammonia, proto- and cytoplasms; compounds of nitrogen and hydrogen, amino acids, hydrocarbons, and protein chains; and in organized orders. Dots, dashes, parentheses, letters, or ellipses turn out to be his aesthetic version of deep sequencing, and add up to someone exploring the spaces between what is known and unknown, imagined, wished for, impossible, and written in visual language. It doesnÔÇÖt matter to me if Way is copying these formulas or grabbing them from his involuting memory, or even if theyÔÇÖre mad. I will never understand what heÔÇÖs saying any better than I understand what all the tens of thousands of unknown microbes on the edge of my cup are in relation to me, or what their life form might be. I take them and WayÔÇÖs work as an indication that the vast part of knowledge, and even the knowable, is some sort of cosmic-psychic-molecular dark matter. It is there even if we canÔÇÖt know it. The way knowing Vermeer is better than Norman Rockwell but never being able to prove it.

Way is especially interested in genesis, some mental meta-genome of molecular biology. In one drawing, the word archegonia┬áappears. The word signifies multicellular structures of plants that contain the ovum, or female gamete. Peer through the foggy hazes of tape and see drawings of embryos, cell membranes. In one drawing, thereÔÇÖs a word that means the tiny passages that sperm moves through. Nearby are references to longevity and aging. I was sure one word, xpiotos, was pure nonsense. In fact, itÔÇÖs an ancient Greek word for fish, and also an archaic sign for Jesus. That Way uses the word in a triptychlike structure containing the words Christ, alpha, and omega┬átells me heÔÇÖs knowingly referring to something Christian, not just babbling, doing busy work.

WayÔÇÖs backstory doesnÔÇÖt matter, nor does his mental illness. What matters is that, as Castrucci tells us, Way, like many artists, ÔÇ£needs to draw at least three or four hours [a day] or heÔÇÖll get sick.ÔÇØ Amen.