A couple of episodes into Show Me a Hero, I realized that I owe David Simon an apology.

The six-part HBO mini-series, which premieres Sunday, is based on Lisa Belkin’s nonfiction book, directed (with a subtlety you might not anticipate) by Crash’s Paul Haggis, and co-written and co-created by Simon and William F. Zorzi, a longtime writer for Simon’s The Wire. It’s about how a court order to build affordable housing in Yonkers tore the city apart in the 1980s and early 1990s. It tells its story in the most Simon-esque way imaginable: by treating all of the characters as social, if not necessarily dramatic, equals, and letting people and institutions be more or less what they probably were, without bending them to fit into a conventional template.

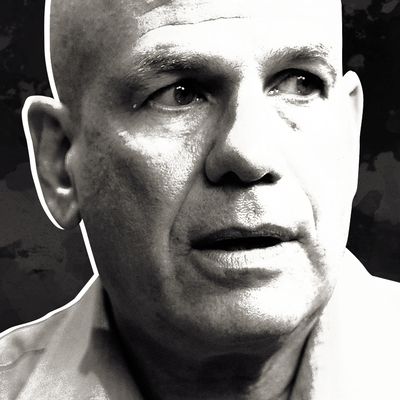

In the foreground, you have a dynamic and immediately involving story about ex-cop turned city councilman Nick Wasicsko (Oscar Isaac), a white man of Polish descent who senses opportunity in the conflict, runs for mayor against a powerful incumbent (Jim Belushi), wins, then finds himself presiding over a city tearing itself apart over race and class. In the background, you have individual stories, none of which are connected at first. They’re about black and Hispanic and white people working in various professions and dealing with distinct problems that are important to them but not of interest to the wider world. There’s Mary Dorman (Catherine Keener), who insists she isn’t racist but merely concerned about property values dropping when people with a different “lifestyle” move into her neighborhood. There’s Norma O’Neal (LaTanya Richardson-Jackson), a visiting nurse who suddenly begins having trouble with her eyesight. There’s Doreen Henderson (Natalie Paul), who was born in the projects but raised in the suburbs, then finds her way back to the projects and tries to keep her life from falling apart. There are a couple of single mothers: Carmen Reyes (Ilfenesh Hadera), an immigrant from the Dominican Republic who’s working herself toward an early grave, and Billie Rowan (Dominique Fishback), who gets pregnant by a petty street criminal and struggles to keep food on her kids’ table while dealing with her lover’s legal troubles.

Almost any other mini-series or movie would have presented these supporting characters as adjuncts to the city council and government stuff, which revolves around middle-class white characters of European descent. They might have gotten one or two scenes apiece. They certainly wouldn’t have been threaded throughout all six hours and given so many scenes that you are forced to accept them as being every bit as important as the characters played by handsome and charming Oscar Isaac; or Winona Ryder, who’s magnetic as a fellow councilmember whom Nick has a crush on; or Alfred Molina, playing a reactionary whose charisma is as undeniable as his politics are ugly.

The fights over housing and zoning are about, and bear directly upon, the lives of the working-class and poor characters whose stories unfold adjacent to the main action. Both sets of stories are presented in a way that leaves no doubt that a general statement is being made — perhaps about how all modern democratic government, even that which considers itself liberal and proactive and compassionate, can be disconnected from the people it wishes to help, and struggle to articulate why it’s doing what it’s doing.

What makes this statement different from most statements in movies and television is how it is made: not through monologues or pronouncements or slogans (though the mini-series has plenty of that; it’s about politics, after all) but through the selection and arrangement of material on the screen. The nagging little voice in the back of the viewer’s head that says, Why are they spending so much time on these supporting characters who have nothing to do with the council? is the same voice that says, in reaction to a current news story, What does the misfortune of strangers have to do with me? You have to make a decision to care equally about every character in Show Me a Hero. That is a tiny decision, granted — this is just a television show, after all — but the mini-series deserves praise for insisting, maybe demanding, that viewers make it, because that request comes from the same impulse that moved a federal judge to order the construction of affordable housing in Yonkers.

Simon’s projects do this sort of thing all the time. It is not a popular or pleasing way to make entertainment. A lot of people resent it, frankly, and his willingness to shrug off such reactions is probably one of the main reasons he’s struggled to win funding for his projects. And it’s why, Peabody Award notwithstanding, he has never won many traditional industry accolades for his work. Although critics loved The Wire and supported the Iraq War drama Generation Kill and the New Orleans panorama Treme — more in spirit than fact, honestly — Simon’s work has been robbed of Emmy and Golden Globe recognition, and his audiences have never been big. His preference for subject matter is just one part of the reason widespread popularity has eluded him.

Yes, it’s significant that he tells stories about poor and working-class as well as middle-class people, and has never had much interest in the rich, except as foils or obstacles for the less fortunate. It’s also true that he’s fascinated by the minute inner workings of institutions, and how they tend to become corrupt and inert thanks to the laziness or selfish ambition of whoever happens to be in charge. Neither of these would necessarily be considered “sexy” things to care about because they deny easy opportunities for escapism. You can’t put expensive clothes and top-dollar haircuts on your characters if the story is about how hard they have to work just to make rent. And you can’t indulge the audience’s desire to watch crusading good guys root out and defeat a handful of bad apples who are preventing an otherwise perfectly fine institution from doing good work — be it the police department and school system of The Wire or the state and local government and construction industries of Treme or the United States Marine Corps of Generation Kill.

But more significant than all that, I suspect, is the way that Simon insists we care about things and people that American entertainment’s clichéd storytelling habits have no use for. Characters who help or hinder the white hero or heroine in a single scene of a major motion picture get not just scenes but whole story lines in Simon’s TV shows. Sometimes they are major characters.

It almost sounds maudlin to say this about a public figure as legendarily grumpy and hectoring as Simon, but the man truly cares, as a democratically minded American citizen should care, about people from all walks of life. And he wants to make everyone care as much as he does, but without oversimplifying what it might take to make his characters feel happy or satisfied or safe or loved, and without tacking happy endings onto stories that shouldn’t have them. And he doesn’t seem to lose much sleep about “likability,” a word that presumes bad faith on the part of viewers because it assumes they won’t care about characters unless they reflect back some idealized aspect of themselves: love of family, pets, one’s parents, etc.

Which brings me to the apology, which in turn brings me back to Treme, and, to a lesser extent, The Wire. Both of those series, like Hero, have huge ensemble casts and divide their attentions as democratically (there’s that word again) as possible among as many different kinds of people as possible. Some are bigger than life, brash, colorful, brilliant, like McNulty or Lester Freamon or Bunny Colvin or Felicia “Snoop” Pearson on The Wire, or Albert Lambreax or Davis McAlary or Creighton Burnette or Ladonna Peters on Treme. Others were smaller or just subtler personalities: Janette Desautel and Annie and Delmond Lambreaux on Treme, Dennis “Cutty” Wise and D’Angelo Barksdale and all those heartbreaking schoolkids from season four of The Wire: Michael, Randy, Dukie, and the rest. And their teacher, Prez, who was mainly just a nice guy who gave a damn. Stirred in among these characters, you’ll find what you might as well call fuck-ups, people so self-destructive and generally irritating that you sometimes find yourself muttering at them as if they were actually in your living room taking up valuable air: Think of Ziggy on season two of The Wire, who had almost no redeeming features save his love for his cousin*; or Sonny on Treme, the junkie musician who spent the first couple of seasons using other people along with drugs and just sort of drifting from failure to failure.

I complained about some of these characters — not the performances, not the writing, but the emphasis given to irritating or self-destructive or seemingly hopeless characters at the expense of other characters I found funnier, more dynamic, more, well, likable. I also complained that Simon and Eric Overmyer, the co-producer of Treme, gave the violent rape of a major character in season two almost exactly as much emphasis as the other subplots happening in that episode, rather than focusing entirely on her for an hour; Simon defended his choice to me on various occasions by saying that although the attack was the most important thing that had happened to that character, it was but one subplot among six or eight, and giving it the same weight as all the others illustrated the world’s ignorance of and indifference to what she was going through. His point was an unpleasant one, but valid, and in retrospect, it feels like more evidence of how consistent his storytelling philosophy is.

Yes, I realize, the sophisticated viewer ought to know better than to fall into this trap, but there are times when the old Hollywood patterns influence a critic’s sympathies even as he decries them. No matter: Simon stuck to his guns and kept embedding less exciting and often less likable characters amid all the ones I adored. And over time, an amazing thing happened: I started to care. I mean really care. I don’t want to spoil what happens to Ziggy on The Wire or Sonny on Treme on the off chance that you haven’t already watched those shows; suffice it to say that the conclusions of their stories are among the most powerful things I’ve ever seen on TV, and they came about as a direct result of Simon and his collaborators insisting that the show, and we, pay attention to them because they’re human, just like anyone else.

In time, I figured out that my resistance to those characters, and my resistance to the almost mathematical equivalency with which Simon doles out screen time, were both vestigial remnants of mentalities that Simon has tried to point out and refute through his stories. His work is more morally and politically and dramatically advanced than almost anyone who naysays it.

Show Me a Hero practices exactly this kind of storytelling, and the approach here might be the most radical yet in a Simon series. When you watch it, you often feel as if you’re simultaneously reading a novel about the main story (the council) and a collection of short stories about all the other characters. What you are seeing in that second set of narratives, of course, are the lives of people who are directly affected by the actions of people in the “novel” part of the tale, even though they don’t realize it, because they either aren’t interested in local politics or are simply too exhausted to follow them closely after a long day of work or taking care of their loved ones. All the stories do converge at the end, and it’s another Ziggy or Sonny type of situation, where you realize, if you didn’t already, that you care just as much about these characters as you do about Nick, with his sarcastic one-liners and disco mustache. You care because Simon and Zorzi and Haggis and all of the other people working behind the scenes on Hero made a decision to care as well, about characters who are typically shoved so far into the margins of this kind of story that they seem more like paper dolls than actual people: proof of the white hero’s goodness; symbols with names.

The kind of storytelling that Simon champions is stubborn, earnest, wise, and informed, but most of all, it’s idealistic, in the most basic way. This attitude embodies one of the foundational presumptions of democracy: that all people are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights. Call it corny or unrealistic or whatever you like: It’s as necessary for the survival of the United States as clean air and water and decent places in which to live. We aren’t supposed to care about other people because they look or talk like us or share our values, Simon’s work tells us. We’re supposed to care because they’re people, and life is short, and we’re all in it together.

* An earlier version of this piece mistakenly referred to Ziggy’s cousin as his brother.